Posted in January, 2010

The January edition of the Magnificat included the story of St. Reinold, religious and marytr (980 c.) He died at the hands of stone masons and later came to be venerated as their patron saint.

There are various versions of his life and martyrdom. St. Reinhold may have been a monk, a knight, a pilgrim–or all three. He may be a fabrication of several different people, stories and legends. Even his murder may have several explanations.

Version I: Reinold was a Benedictine monk of the monastery of Saint Pantaleon in Cologne, Germany. He was entrusted with the duty of overseeing the construction work to complete the abbey.

Reinold was murdered by the stone masons working on the building. They beat him to death with their hammers and threw his body into a pool of water near the Rhine river.

In one telling, Reinold is killed due to his “over-strenuous diligence,” which incurred the hostility and bitter resentment of the stone masons. In a second account, he was murdered by stone masons who were annoyed that Reinold worked harder and with more skill then they did.

Reinold’s fellow monks were unable to find his body until its whereabouts were made known in a private revelation to an infirm poor woman. His body was taken to the abbey and buried with honor.

Version II: St. Reinold was drawn from the story of Renaud, the youngest son of Duke Aymon of France. He was supposedly a descendant of the sister of Charlemagne, and the 4th son mentioned in William Caxton’s romantic poem, Romance of the Foure Sonnes of Aymon.

The four sons of Duke Aymon are Renaud, Richard, Alard and Guiscard, and their cousin is the sorcerer, Maugis. Maugis was raised by the enchantress Oriande la Fee. He won the magical horse Bayard–who could understand human speech–and the sword Froberge which he later gave to Renaud.

The oldest extant version of the story of Renaud de Montauban and his cousin, Magris, was the anonymous Old French chanson de geste Quatre Fils Aymon which dates from the late 12th c.

In the tale, Renaud and his three brothers were sons of Aymon of Dordone. They flee from the court of Charlemagne after Renaud kills another of Charlemagne’s nephews in a brawl over a chess game. Renaud kills the man by battering him with a chess board. A long war follows, during which Renaud and his brothers remain faithful to the Christian chivalric code.

The four brothers are pardoned on the condition Renaud go to the Holy Land on crusade (or on a pilgrimage), and their magical horse Bayard, who could expand his size to carry all four brothers, be surrendered to Charlemagne.

Charlemagne orders Bayard to be drowned by chaining it to a stone and throwing it in the river Meuse, but the horse escapes and lives forever more in the Ardennes forests.

After further adventures soldiering in the Holy Land, Renaud returns home. On his return he abandons his home and gives himself up to religion. He eventually makes his way to Cologne and enters the monastery of St. Pantaleon, where be works as a mason on the Church of St. Peter. He is murdered by jealous fellow masons. His body is miraculously saved from the river and magically makes its way home to his brothers in a cart.

In art, St. Reinold is depicted with armor, reflecting the tradition that he had been a soldier before entering monastic life. He is also shown as a Benedictine monk with a stone mason’s hammer; as a monk being killed by stone masons, and as a dead monk being thrown in water.

Besides his identity, I have three other mysteries to solve: 1) why was he murdered; 2) why was he named a saint; and strangest of all, 3) Why he was named a patron saint of the group of people who killed him?

Here are my two versions:

Story 1: Brother Reinold is two people: pious in prayer and a mean, overbearing, and cruel overseer. Hatred and resentment build up among the stone masons he supervises. He oversteps his bounds one day, striking, kicking or punishing someone he bullies to push them to work harder. The man or his friend strikes back in self defense or in a fury. The others finish the job and try to get rid of the body. A local poor woman knows where the body was disposed, and tells the monks the place came to her in a dream from God. The monks find the body and attribute it to divine revelation. They don’t pursue the killers because they know Reinold was a creep and they need their abbey completed. Over the years, long after all the murderers and monks are dead, Brother Reinhold becomes a patron saint of stone masons because he was associated with them, and his *martyrdom* came at their hands.

Story 2: A former warrior named Renaud shows up at the Monastery of St. Pantaleon in Cologne after soldiering in the Holy Land. They can’t pronounce his French name and it comes out sounding like “Reinold.” He comes from an aristocratic family, a descendant of the legendary Charlemagne, and cousin to a famous sorcerer. He makes sure everybody knows it, and the fact he has given it all up to follow a monastic life. He is tough, skilled and hard, and drives himself and everyone around him with a religious zeal. Newly devout, Renaud hectors the other half-pagan stone masons about their lives and picks fights with them. One day, they turn on him in a group and kill him. The body is never found, although local legend has it returning to France in a magical cart–derived, no doubt, from his stories about his horse, Bayard.

Could there have been a darker meaning behind his death? Some historical evidence points to a Christian-Pagan clash or ritual: according to the book, The Ciphers of the Monks by David A. King, German stone mason’s marks (Steinmetzzeichen) were often based on the runes. They chiseled these marks into the stones, especially the foundation stone, as their signature. I can see how that would fill a zealous Christian with horror and anger–an affront to the consecration of the building.

Two hundred years earlier another Benedictine, St. Boniface, was bludgeoned and hacked to death for insulting the gods.

Medieval people also used “foundation sacrifices” or burials to ensure the stability of a building–castle, bridge and sometimes, churches. They also had a tradition of sacrificing people to placate the spirits of a place. The sacrificed person, in turn, became its protector. Often these were children, sometimes adults, who were entombed alive within the structure. In other sacrifices a dead person was thrown into a pool of water as a votive offering. Could this been what happened to Reinold?

If a monk-mason named Reinold ever existed, and whatever the reasons were behind his death, ultimately the church profited by his romantic and legendary associations. Over time he became “St. Reinold,” martyred for the faith by fellow stone masons jealous of his example.

In one of those delicious ironies the Catholic Church is so famous for, he becomes their patron saint and protector.

I did notice that mason’s hammers bear a strong resemblance to Mjollnir, the hammer of Thor. Just a coincidence, or a subtle clue to his killers?

Mary Daly, 81, died two weeks ago, mostly forgotten, certainly unshriven. Carolyn Moynihan, deputy editor of MercatorNet, noted that Daly “seems to have departed this life as a kind of orphan herself. The New York Times obituary notes that she ‘leaves no immediate survivors’. No family on earth? No father in heaven? I hope it really was not like that for Mary Daly at the end.”

After her two first two books, which stood the Catholic world on its head, Mary Daly spun off into the ether, writing books with titles like: Outercourse: The Be-Dazzling Voyage; and Quintessence..Realizing the Archaic Future. Daly created her own language, but most people weren’t interested in learning it. She lost her hold on the larger Catholic imagination.

In the 80s the lesbian herd moved past her, too, migrating on towards the mainstream–“Ellen,” “The L Word,” “Rachael Maddow,” “Suze Orman,” human rights, marriage rights and child rearing. The labrys pendant was lost or forgotten. Daly was, too.

Mary Daly was the quintessential Irish Catholic girl. Born October 16, 1928, in Schenectady, NY, she went all through Catholic schools, and received a BA from the College of St. Rose in Albany, NY and a MA from Catholic University in Washington, DC. After earning her doctorate in religion from St. Mary’s College in Notre Dame, Indiana, in 1953, she went on to obtain two degrees from the University of Freiburg in Switzerland, since no U.S. institutions at the time offered theology doctorates to women.

Dr. Daly was hired as an assistant professor at Jesuit-run Boston College in 1967, when the school only enrolled men. She started as a reformist, and her first book, The Church and the Second Sex, (1968) she argued that the Catholic Church was patriarchal in nature and had systematically opposed women for centuries. In response, the college attempted to dismiss her, but the support she received from students and the public kept her in the classroom.

As a student in the early ’70s at Trinity, an all-women’s college in Washington, DC, I was thrilled about Mary Daly and her books. “Someone speaking for us,” I thought as I picked one up, “someone speaking the truth about what it’s like to be a woman in the Catholic Church.”

Sr. Joan Chittister reflected on Daly’s impact on history: “I learned how to look newly at things I’d looked at for so long that I was no longer really seeing any of them. Women need to thank Daly for raising two of the most important theological questions of our time: one, whether the question of a male God was consistent with the teaching that God was pure spirit, and two, whether a church that is more patriarchal system than authentic church could possibly survive in its present form. These two questions have yet to be resolved and are yet rankling both thinkers and institutions.”

Daly came out as a lesbian in the early 70s–when she was in her 40s. She began to study ancient cultures, and came to regard all major modern religions as oppressive to women, a view expressed in her second book, Beyond God the Father (1973). Her original critique of the Roman Catholic Church as a bastion of patriarchy was extended to the entire Christian tradition. She rejected Christianity’s focus on a monotheistic deity and what she attacked as its intrinsic patriarchy. She asserted that Christianity’s focus on Jesus Christ was just another dimension of its patriarchy–a Savior in a male body.

As Margaret Elizabeth Kostenberger explains, Daly’s “compete rejection of Scripture” on the basis of its “irremediable patriarchal bias” took her far outside the Christian faith. While other feminists called for the adoption of female or gender-neutral language for God, Daly attacked those efforts as half-measures that fail to take the “phallocentricity” of theism seriously.

Her famous dictum, “If God is male, then the male is God,” stood at the heart of her argument against religion. She accused Christianity of “gynocide” against women and suggested that all monotheistic religion–and Christianity in particular–is “phallocentric.”

“I urge you to sin,” she wrote to women readers. “But not against these itty-bitty religions, Christianity, Judaism, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism–or their secular derivatives, Marxism, Maoism, Freudianism and Jungianism–which are all derivatives of the big religion of patriarchy. Sin against the infrastructure itself!”

In 1999 Professor Daly left Boston College after a male student threatened a lawsuit when he was denied a place in her class on feminist ethics. She had long limited enrollment in some advanced women’s studies classes to women only, maintaining that the presence of men there would inhibit frank discussion.

What happened to Mary Daly, that she imposed the same gender barriers in her classrooms as she experienced? Daly went to Europe for advanced degrees because no U.S. Catholic university would accept a woman in a theology program. Years later, Daly bared men from her advanced courses in women’s studies because she felt their presence would have a negative impact on the other students. Men, she said, “have nothing to offer but doodoo.”

It may be retribution, but it doesn’t seem right. How do you rail against a system of discrimination, and then implement it with glee yourself?

So I am left with a mystery to solve: why did Mary Daly, a “post-Christian,” continue to affiliate with Boston College, an unabashedly Catholic institution? Love and hate are bound very closely. Daly was never indifferent.

Perhaps it began with a girlhood hurt. Daly wrote about her intellectual formation in a 1996 article in the New Yorker “Sin Big,” in which she recalled being mocked by a male classmate, and altar boy, at her parochial school because she could never “serve Mass” because she was a girl.

“(T)his repulsive revelation of the sexual caste system that I would later learn to call ‘patriarchy’ burned its way into my brain and kindled an unquenchable Rage,” she wrote.

Daly described herself as a pagan, an eco-feminist and a radical feminist in a 1999 interview with The Guardian newspaper of London. “I hate the Bible,” she told the paper. “I always did. I didn’t study theology out of piety. I studied it because I wanted to know.”

So with all that, how could she in good conscience continue to teach at a Catholic university?

Here’s what I think: at BC, Daly could be an outlaw, get a paycheck, credibility for book deals, and still have the protective mantle of identity that gave her cachet: a professor at a highly regarded Catholic university.

She lived on the piercing insights she fearlessly raised 40 years ago. But Daly had ceased to be a theologian, and even her philosophical writing declined into self-important gibberish. She should have taken her own advice–a person becomes stagnant if they don’t move on.

If you’re going to call yourself a Post-Christian, then be Post-Christian. If you have moved on… move on, and stop clinging to institutions that you say you no longer believe in.

A man wrote the best epitaph for Daly that I have read: “When I was in the seminary, attending class at B.C. during the eighties, Mary Daly was a joke. Imagine my surprise when, years later, as a purely cynical move to impress a feminist scholar, I cited Mary Daly in a paper, but was not able to put her work down. Although her work never persuaded me to abandon my beliefs, or my own thinking, Mary did push me to consider a whole world of concern that years earlier I would have dismissed as nonsense. Now, when I think of her, I do not think of a nut, or a totally whacked out feminist. I think of a pioneer, who, although not worthy of discipleship, is certainly worthy of being taken seriously as a thinker and a human being. I wish I had met her, although I’m not sure of how it would have turned out.”

Thumbing through my copy of Magnificat in church last week, I came upon the story of Saint Ethelfleda. Her tale breathes a warm, oddball humanity–in contrast to the usual Magnificat fare of sanctity, torture and grim death for aspiring saints.

Saint Ethelfleda is someone I can relate to: swims naked, prays outdoors, entertains generously, and inspires young people.

Here are her miracles of renown, and those of her teenage admirer – who went on to surpass her in weird tales.

Saint Ethelfleda (c.930 – Feast Day – October 23) was a member of the Anglo-Saxon nobility. Following the death of her husband, she spent the rest of her life as abbess of Romsey. Her devotional acts included chanting psalms while standing naked in the cold water of the River Test.

One day, as Ethelfleda was preparing for a visit from her kinsman, King Athelstan, the royal chamberlain arrived in advance to see if she had the provisions necessary to host the king and his large retinue. Upon being informed by the chamberlain that she lacked an adequate supply of ale, Ethefleda answered, “My patroness, the Virgin Mother, will send me an abundance of ale.” She thereupon withdrew to an oratory of the Blessed Virgin, where she ardently prayed for heavenly intervention.

When on the next day the king and his men arrived after attending Mass, Ethelfleda’s modest barrel of ale supplied all they wanted without running dry.

Her legend also tells that she spent time with the king and queen at court, where Ethelfleda’s habit–for “ascetic reasons” –of bathing in the nude at night was the occasion of the queen’s nervous illness, brought on by the queen’s “indiscreet curiosity” when she followed her to see where she went. The queen was afterward cured by the abbess’ intercession.

The Magnificat story ended by saying the elderly Ethelfleda was frequently visited by a teenage boy who drew inspiration from her example. The youth was the future abbot of Glastonbury and archbishop of Canterbury – Saint Dunstan.

Saint Dunstan (909?-May 19, 988, Feast Day – May 19) was born near Glastonbury and lived for a time in the household of Saint Ethelfleda’s kinsman, King Athelstan. The dreamy young man became a great favorite of the king, his relatives and other members of the court became jealous and envious. They accused Dunstan of studying heathen literature and black magic, and prevailed upon the king to order him to leave the court.

As he was departing Dunstan was attacked. According to various accounts, he was beaten and thrown in a duck pond or cesspool, where his enemies pushed him face down in the muck.

He fled to Winchester and entered the service of Bishop Aelfheah the Bald, who endeavored to persuade him to become a monk. Dunstan was doubtful about whether or not he had the vocation to celibate life, but an outbreak of tumors all over his body–probably from blood-poisoning caused by the treatment to which he had been subjected, changed his mind.

He made his profession at the hands of St. Aelfheah (“Elf-high”) and returned to live the life of a hermit at Glastonbury, working on his forge and playing his harp. Here the Devil is supposed to have appeared to tempt him, and Dunstan seized him with his blacksmith tongs and made him promise never to enter a house with a horseshoe over the doorway.

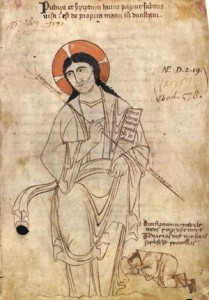

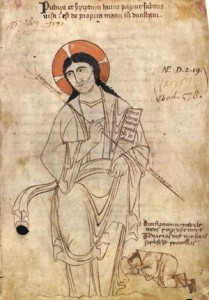

Dunstan also worked as a silversmith and in the scriptorium while he was living at Glastonbury. Dunstan drew his own self-portrait in the small, kneeling monk beside Christ in the Glastonbury Classbook. The inscription reads: “I ask you, merciful Christ, to watch over me, Dunstan. May you not permit the Taenarian storms to swallow me.”

Did Saint Dunstan delve into occult practices in his youth? Perhaps. It has been speculated that his famous fight with the Devil was in fact a battle with his own desire to fully resume his former practices and studies.

The sketch in his own hand showing Dunstan holding the hem of Christ’s garment; and his petition for Christ’s aid to save him from the underworld–or Hell–may be more illuminating than we realize about his inner and outer life.

The “heathen literature” Saint Dunstan studied when he was younger may have been some Irish manuscripts describing druid practices and beliefs that survived Saint Patrick’s efforts at destroying all of them. His early education was received from Irish monks at Glastonbury. Dunstan obviously had access to manuscripts by Ovid or other ancient Greeks with his reference to “Taenarian storms” – Taenarius or Taenarus is the path or gateway to the underworld or Hades.

At least one person thought St. Dunstan might have practiced or dabbled in magic: William Godwin (1756-1836) , who included him in his book, Lives Of The Necromancers: Or An Account Of The Most Eminent Persons In Successive Ages, Who Have Claimed For Themselves, Or To Whom Has Been Imputed By Others, The Exercise Of Magical Power. The book was published in 1834. The other necromancer of ancient Britain Godwin cited was Merlin.

Goodwin asserted that at least one of Saint Dunstan’s “miracles” was really magic. As the story goes Eadmund, a young king of 18, sought the advice of Dunstan, but the jealousy of the courtiers was aroused and he was driven from court.

“For, a few days later, the king rode out to hunt the stag in Mendip Forest. He became separated from his attendants and followed a stag at great speed in the direction of the Cheddar cliffs. The stag rushed blindly over the precipice and was followed by the hounds. Eadmund endeavoured vainly to stop his horse; then, seeing death to be imminent, he remembered his harsh treatment of St. Dunstan and promised to make amends if his life was spared. At that moment his horse was stopped on the very edge of the cliff. Giving thanks to God, he returned forthwith to his palace, called for St. Dunstan and bade him follow, then rode straight to Glastonbury. Entering the church, the king first knelt in prayer before the altar, then, taking St. Dunstan by the hand, he gave him the kiss of peace, led him to the abbot’s throne and, seating him thereon, promised him all assistance in restoring Divine worship and regular observance.” (Catholic Encyclopedia)

At that time Dunstan was 19 or 20 years old. He became the Keeper of the Treasure and the chief adviser to the king. When his royal friend was stabbed in May 946 by the outlaw Leof, the abbot buried him in the abbey.

It sounds like a spell Merlin would have concocted to change the king’s heart.

A counselor to successive kings, Dunstan continued to have potentially fatal run-ins with them. On the day of his coronation in 956, newly crowned King Eadwig left his banquet to join two women in bed–the king’s foster-mother, and her daughter, Aelfgifu. Dunstan followed in a fury and dragged the startled king back to the hall and his knights. The episode, no surprise, led to Dunstan’s exile and flight for his life.

Besides the number of times he was thrown out of court and then restored, Dunstan’s life was notable for the number of visions of angels and demons, including a warning by angels that he would die within three days. He did.

“..for all his life this unique and marvellous man had revelation of things distant in space and in time, and his happy spirit, full of the artist, metal-worker, lover of tunes and gay, lived on the edge of this world; the good and the evil of the unseen supported and attracted him as they do such few as are placed on the outposts of humanity.” (Hilaire Belloc, History of England)