Posted in category "Saints"

A healthy number of saints’ stories feature people who were “called to chastity” or to a relationship with Christ vs. marriage. All kinds of fantastic legends and tales ensued about the lengths to which these people would go to avoid marriage and connubial sex. Ultimately, they were all successful in their quest to avoid sex with members of the opposite sex. They ended up living alone (rarely) or with a same-sex companion (often) or same-sex community in a wilderness setting (usually).

Thecla at her window listening to Paul

St. Thecla the Evangelist is one of those saints. She would face anything but marriage.

Thecla’s story is preserved in the Acts of Paul and Thecla, an apocryphal story of Paul’s impact on a young virgin, Thecla, and her subsequent trials, adventures and spiritual leadership as his disciple. She infuriated many Church Fathers, including Tertullian, who griped that some Christians were using the example of Thecla to legitimize women’s roles in teaching and baptizing.

According to Acts, Thecla was a beautiful young woman of Iconium (now Konya, Turkey) whose life was transformed when she heard St. Paul preaching in the street beneath her window. She announced her intention to break off her engagement and to embrace a life of chastity. Her finance was furious. Her family was scandalized. They denounced her to the governor who had her arrested and condemned to death. Thecla was tied naked to a stake, but a miraculous thunderstorm put out the flames. She is saved. Once home, Thecla disguises herself as a youth and escapes to reunite with Paul and travel to Antioch.

While traveling, she is sexually assaulted by Alexander, a prominent man of Antioch. One account reads: “Repulsing the assault, she tears his cloak and knocks the wreath from his head. Alexander (the would-be ravisher) brings her before the magistrate who, despite the protests of the women of the city, again condemns Thecla to death, this time ad bestias. Pleading to remain a virgin until her death, she is taken in by ‘a certain rich queen, Tryphaena by name,” who lost her own daughter. (Tryphaena was the widow of Cotys, King of Thrace and a great-niece of the Emperor Claudius. In Romans 16:12, Paul sends greetings to a Tryphaena.)

Queen Tryphaina

Thecla is allowed to return to Tryshaena. She rides a lioness (who licks her feet) and is paraded through the city. The next morning, Alexander comes for her and escorts her to the arena to die. There she is stripped and thrown to wild beasts. A lioness (presumably the one who licked her feet) protects her from the attacks of lions, bulls and bears. Thecla prays, and throws herself into a trench of water (an euripus) and baptizes herself. The water is full of ferocious and hungry seals. A cloud of fire covers her nakedness and kills the vicious seals. The women in the stands of the arena cast fragrant nard and balsam into the area, which had a pacifying effect on the remaining wild animals. The awestruck governor releases Thecla and she returns to the palace of Queen Tryshaena. Refusing all entreaties to stay with the queen, Thecla dresses in male clothing and sets out to find Paul. She tells him that she baptized herself, and had been commissioned by Christ to baptize and preach in his name. According to the story, Paul recognized her as a fellow apostle and encouraged her to preach the Gospel. Wherever she went, “a bright cloud conducted her on her journey.”

Thecla encouraged women to live a life of chastity and to follow the word of God. She returned home to find her finance had died and her mother indifferent to her preaching. She left, and in one version of her story, she dwelt in a cave in Seleucia Cilicia (southern Turkey) for 72 years and formed a monastic community of women, whose members she instructed “in the oracles of God.”

In another version, Thecla passed the rest of her life in a rocky desert cave in the mountains near the town of Ma’aloula (Syria). She became a healer and performed many miracles. She remained persecuted, and men still conspired to rape and kill her. Just as she was about to be seized, Thecla cried out to God for help. A fissure opened in the stone walls of her cave and she disappeared. It is said that she went to Rome and lay down beside Paul’s tomb.

Thecla and animals

Her cave became an important pilgrimage site in early and medieval Christianity. Today visitors can still see Thecla’s cave and the spring that provided water for her. The nuns who live at the Mar Thecla monastery will tell you her story and show you the opening in the rock where the saint escaped.

There are many wonderful parts of St. Thecla’s story, beginning with her determination to live her life following her calling to evangelize, rather than accede to family or societal expectations. Her protection by animals, the public affirmation by groups of women, are also very positive. She was unashamed of her nakedness when she was led twice to the arena to die. She was proud of her body, her virginity, and her sole possession of it. The biggest surprise was her encouragement by St. Paul ( wives-be-subordinate-to-your-husbands), accepting her as a fellow apostle. The ugly, horrifying constant throughout her life is the desire by men to rape Thecla or kill her if she won’t submit to their authority. Men who are rapists do not believe that they are the problem–females (or males) who aroused them are at fault. What can Christianity do to change this perception?

The Report on the Holy See’s Institutional Knowledge and Decision-Making Related to Former Cardinal Theodore Edgar McCarrick (1930-2017) was issued by the Vatican’s Secretariat of State on November 10, 2020. The report was authored by U.S. attorney, Jeffrey Lena, who had previously represented the Vatican in several sex abuse cases. The 449-page document is the result of a two-year investigation, prompted by the public demand by Archbishop Carlo Vigano that Pope Francis resign for his alleged leniency to Cardinal McCarrick. Archbishop Vigano’s “testimony” was released on August 25, 2018 and splashed all over ultra-conservative Catholic media outlets. Gossipy and salacious, he pointed the finger at Pope Francis as the chief villain. Since then, the Vatican had been under heavy pressure to provide an explanation for Cardinal McCarrick’s rise, and his continued influence within the Church after rumors and accusations of sexual activity circulated for several decades.

Before his downfall, Cardinal McCarrick was a star among the U.S. Catholic hierarchy, both for his fund-raising prowess and his sophistication about American and global affairs. He brought the Vatican millions of dollars from the U.S. for papal charities.

Who are the main villains in The McCarrick Report?

#1 – Cardinal Theodore McCarrick. A man who used his position, influence, and financial gifts to manipulate or coerce seminarians and altar servers to have sex with him; and protect him from any career consequences. Many of his victims were children of family friends. All of the seminarians depended on his patronage to be ordained.

#2 – Pope John Paul II (1979-2005) – Pope John Paul II turned a blind eye to clerical sexual activity. His main concerns were freeing Poland from communism, keeping communism out of Latin American, and stamping out North American and European reformers and dissenters. His courtiers had free rein, especially after the mid-1990s when he began to suffer from Parkinson’s Disease, and became increasingly incapacitated mentally and physically. His hubris and handlers kept him propped up in Peter’s Throne so the good times could continue to roll. He ignored numerous complains about McCarrick, and continued to promote him from Bishop of Metuchen, NJ (1981), to Archbishop of Newark, NJ (1986), Archbishop of Washington, DC (2000), and finally named McCarrick a cardinal (2001). The best article I ever read about Pope John Paul II’s culpability in the Church’s sex abuse holocaust is Maureen Dowd’s A Saint, He Ain’t. Poland’s bishops lobbied hard for John Paul II’s early beatification and canonization but were rebuffed in 2019 when they petitioned the Vatican and fellow prelates worldwide to have him elevated still further as a Doctor of the Church and patron saint of Europe.

#3 – Cardinal Stanislaw Dziwisz. The McCarrick Report contains 45 references to Dziwisz, who first met McCarrick while visiting New York with the then, Cardinal Karol Wojtyla in 1976. When Karol Wojtyla became Pope John Paul II in 1978, Dziwisz served as his personal secretary for the Polish pontiff’s entire 27-year reign. Cardinal Dziwisz is accused of covering up sexual abuse in exchange for money. One of McCarrick’s victims, James Grein, said he once accompanied McCarrick on a trip to the Vatican with a briefcase containing envelopes full of money. The envelope addressed to Dziwisz held $10,000.

The role of the former papal secretary in stifling sex abuse claims and protecting clerical abusers as favors or for money has come under recent scrutiny in Poland. A 90-minute documentary, “Don Stanislao” was recently shown on TVN24 in Poland. The film aired a long list of accusations about Dziwisz, from covering up for his friends in the seminary to the his role in protecting the late Father Marcial Maciel, the disgraced founder of the Legionaries of Christ, and former Cardinal McCarrick. The documentary also detailed how as archbishop of Krakow he ignored complaints against subsequently convicted local priests.

#4 – Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI – Pope Benedict asked Cardinal McCarrick to step down as archbishop of Washington, DC in 2006. Since he was 76, a year past the age of retirement, the request wasn’t extraordinary. “Over the next two years, Holy See officials wrestled with how to address issues regarding Cardinal McCarrick,” the report’s summary states. “Ultimately, the path of a canonical process to resolve factual issues and possibly prescribe canonical penalties was not taken,” the summary concludes. “Instead, the decision was made to appeal to McCarrick’s conscience and ecclesial spirit by indicating to him that he should maintain a lower profile and minimize travel for the good of the Church.” That didn’t happen; McCarrick continued his global lifestyle and high visibility.

Pope Benedict did and said nothing. Benedict also gave himself the excuse that McCarrick was already retired in not initiating formal disciplinary proceedings. “God’s Rottweiler” as the head of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (1981-2005) silenced and censored numerous theologians, bishops, priests and religious during his tenure. He decried secularization, liberation theology, feminism, homosexuality, religious pluralism, and bioethics. He gave clerical sex abuse and rape a pass.

#5 – Four New Jersey Bishops. These men vetted Archbishop of Newark McCarrick for the prestigious Washington, DC appointment—Bishop Emeritus Edward Hughes, Metuchen; Bishop John M. Smith, Trenton; Bishop James McHugh, Camden; and Bishop Vincent DePaul Breen, Metuchen. Of the four, only Bishop Edward Hughes advised that it would be “unwise to consider the Archbishop for any promotion or additional honor.” Even so, Bishop Hughes did not pass on reports from seminarians and priests who told him they had been abused by McCarrick. Both James McHugh of Camden and John Smith of Trenton witnessed McCarrick groping a seminarian at a dinner party but never reported it.

All the New Jersey bishops confirmed the rumor that McCarrick persuaded seminarians to share his bed at his New Jersey Shore house. The Vatican report does not explain by these bishops would not regard sleeping with young men—at minimum–as a serious impropriety and lack of judgement. Nor does it indicate why it didn’t raise a red flag for sexual activity for Vatican officials. The report also included an allegation by an unnamed Metuchen priest who accused McCarrick of having sex with a third priest in June 1987. The accuser was not originally believed since he “had previously abused two teenage boys.”

As expected, The McCarrick Report has plenty of dirt to throw on the legacy of Pope Saint John Paul II: he didn’t bother to investigate sex crimes. That way, he never had sufficient evidence requiring him to act. Because he chose to look the other way, thousands of children, teenagers, seminarians, and vulnerable adults were victimized by clerical predators. The failure of his moral leadership deeply wounded the Catholic Church and many people of faith.

The Report highlights repeated failures in the processing of vetting bishops, a process that often seems more focused on personal connections and ensuring unquestioned adherence to doctrine rather than raising red flags on inappropriate or criminal behavior.

The system in place where archbishops are expected to police abuse by bishops is totally inadequate.

Finally, it shows how certain Vatican prelates—Cardinal Dziwisz and Cardinal Sodano chief among them—were happy to let crime and sin slide if they were paid.

St. Hildegard of Bingen was a mystic, writer, composer, polymath, and Abbess of Rupertsberg Abbey in Germany. She suffered from migraine headaches. Migraines are often preceded or accompanied by visual hallucinations. In her medical treatise Causae et Curae, Hildegard described the migraine in detail but never connected this diagnosis to herself. Similarly, Hildegard loved a younger woman deeply, strongly, passionately, but never connected lesbian desire to herself, either in her writing or her art.

The “Egg of the Universe,” an illumination of one of Hildegard’s visions, bears a striking resemblance to a woman’s vulva, but Hildegard doesn’t describe it as such: “By this supreme instrument in the figure of an egg, and which is the universe,” she wrote, “invisible and eternal things are manifested.” Is it an egg, or is it a celebration of female sexuality?

In the illustration, the outer planets of Mars, Jupiter and Saturn correspond exactly with the vagina, urethra, and clitoris. The labia is also easy to identify. While the illustration is egg-shaped, so is the vulva. Didn’t it occur to Hildegard that her holy vision produced a detailed and accurate picture of a woman’s external genitalia? The finger or tongue-like shape in the opening is also revealing.

Hildegard recorded her visions in Scivias, a three-volume work completed in 1151 or 1152 when she was 53. It took her ten years to complete. Scivias contains 26 visions that she experienced. In each vision, she describes what she saw, and then records explanations that she heard which she believed to be the “voice of heaven.” She had a lot to say about male and female roles and homosexuality. The prescriptions against wearing men’s clothes, lesbian sex and masturbation appear in the Part II, Vision 6, The Sacrifice of Christ, and the Church.

- Men and women should not wear each other’s clothes except in necessity.

“A man should never put on feminine dress or a woman use male attire, so that their roles may remain distinct, the man displaying manly strength and the woman womanly weakness; for this was so ordered by Me when the human race began….But as a woman should not wear a man’s clothes, she should also not approach the office of My altar, for she should not take on a masculine role either in her hair or in her attire.”

- God will judge all perpetrators of fornication, sodomy, and bestiality.

“And a woman who takes up devilish ways and plays a male role in coupling with another woman is most vile in My sight, and so is she who subjects herself to such a one in this evil deed. For they should have been ashamed of their passion, and instead they impudently usurped a right that was not theirs. And, having put themselves into alien ways, they are to Me transformed and contemptible.”

“And women who imitate them (men) in this unchaste touching and excite themselves to bodily convulsions by provoking their burning lust, are extremely guilty, for they pollute themselves with uncleanness when they should be keeping themselves in chastity.”

I had to wonder what was going on in Hildegard’s mind when she was dictating these passages to her young assistant, Richardis von Stade. Richardis seems to have been Hildegard’s closest friend and companion. Well educated and a talented writer, she transcribed Hildegard’s visionary writings and prepared them for production as manuscripts. “When I wrote the book Scivias,” Hildegard wrote, “I bore a strong love to a noble nun…who connected with me in friendship and love during all those events, and who suffered with me until I finished this book.”

Were Hildegard and Richardis lesbians? Did they ever have a physical relationship? Did they touch or hold one another? Did they lie in bed and imagine physical intimacy? Did they look for one another in the chapel? Did they feel an electricity in one another’s presence? Many people, nuns included, separated their same-sex love and sexual desire from the repulsive view of homosexuality that they were taught and in which they believed. Hildegard may have compartmentalized the prohibition to specific practices (“playing a male role in coupling with another woman”) and seen her own relationship with Richardis as qualitatively different in the way they made love or emotionally interacted. There was certainly a strong erotic component in their relationship and work together.

When Richardis’ family arranged for her to leave Rupertsberg Abbey to become Abbess of Bassum, Hildegard became extremely upset, desperate, almost unhinged. She wrote letters to the young woman’s family, urging them not to let her leave Rupertsberg, and begged Richardis not to go. Hildegard wrote to the bishop, her superior and even the pope to no avail. Richardis left Rupertsberg in 1151. She died a year later October 29, 1152 at Bassum Abbey of an unspecified illness. She was 28 years old. Richardis may have accepted the abbess of Bassum as a position befitting her social rank.

“I so loved the nobility of your character,” Hildegard wrote, “your wisdom, your chastity, your spirit, and indeed every aspect of your life that many people have said to me: What are you doing?”

Richardis’ brother, Hartwig, the Archbishop of Bremen, wrote to Hildegard shortly after Richardis died. Hartwig had been influential in obtaining the Bassum appointment for his sister, Richardis. “I write to inform you that our sister—my sister in body, but yours in spirit—has gone the way of all flesh, little esteeming the honor I bestowed upon her..I am happy to report that she made her last confession in a saintly and pious way and that after her confession she was anointed with consecrated oil. Moreover, filled with her usual Christian spirit, she tearfully expressed her longing for your cloister with her whole heart…Thus I ask as earnestly as I can, if I have any right to ask, that you love her as much as she loved you, and if she appeared to have any fault—which was indeed was mine, not hers—at least have regard for the tears that she shed for your cloister, which many witnessed. And if death had not prevented, she would have come to you as soon as she was able to get permission.”

Hildegard’s grief produced another sublimated creative masterpiece: Ordo Virtutum (“Play of Virtues.”) Richardis was obviously the inspiration for this musical morality play about a soul who is tempted away by the devil and then repents.

At her death, Richardis experienced a level of awareness and humility that Hildegard, with all her visions, never achieved. She admitted she made a mistake in leaving the woman she loved. What is not clear is exactly why Richardis left Hildegard and Rupertsberg Abbey. Did she capitulate to the social and political maneuvering of her family? Was it a need to assert her own independence after many years as Hildegard’s assistant? Or, was the sexual and emotion tension of in her relationship with Hildegard too hard to endure?

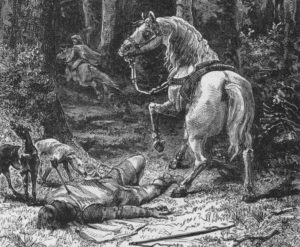

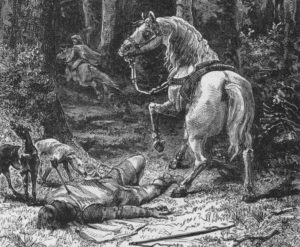

King William II of England, also called William Rufus, was killed by an arrow while he was hunting in New Forest on August 2, 1100. It was a fortuitous death for his younger brother, Henry Beauclerc, who became King Henry I three days later. It was a convenient death for Archbishop Anselm of Canterbury, who battled King William constantly over church revenues and appointments and could now return from exile in France. It was also providential for King Philip I of France. King William regularly sent military expeditions to extend his influence and lands in Normandy, Maine and the Vexin. William Rufus was planning a new campaign in France when he was killed. His successor, King Henry I, immediately cancelled it.

For centuries, the generally accepted explanation for King William’s death was a hunting accident. That is possible. His older brother, Richard, was killed in a hunting accident in New Forest. But William’s death by an errant arrow was never completely accepted. Some writers and scholars believe that he was assassinated in order to put his brother on the throne. Could Henry Beauclerc, some nobles and the French king have colluded to kill him during a hunt? Could rumors of a possible assassination attempt circulate through monasteries in England and France? Archbishop Anselm and other high-ranking clerics certainly lent support to the killing; they justified it as divine intervention by God to remove an evil and immoral king.

William’s death is wrapped in several other mysteries. Why the large number of dreams foreshadowing his death? Were they inspired by rumor or gossip? The victim, his friends and enemies all dreamed of his death by an arrow. Why did Walter Tirel abandon William’s body and leave for France so abruptly?

Two Homosexuals – William and Anselm

The death of King William II may have had its roots in his struggles with Archbishop Anselm. The king needed money for his soldiers and military campaigns. To fund them, he left the sees vacant and pocketed the revenues himself. Archbishop Anselm was a proponent of the Gregorian Reforms, eliminating secular investiture of bishops and married priests. A clash was inevitable.

It’s easy to speculate that both men were homosexual. William, even as king, never married, had no offspring, and no reported mistresses or liaisons with women. One clerical chronicler, Orderic Vitalis, described the men at court as having too tight tunics, pointed shoes and hair down their backs like whores. The court was full of “sodomites.”

Anselm’s homoerotic emotions are evident in his passionate letters to fellow monks. They are full of yearning, desire, and anguish. We don’t know if he physically acted on his feelings. Either way, they are quite a contrast to his admonishment to King William to rid his court and kingdom of homosexuality. Anselm asked the king’s leave to call a national synod of bishops. William responded: “What will you talk about in your council?” “The sin of Sodom,” answered Anselm, “to say nothing of other detestable vices which have become rampant. Only let the king and the primate unite their authority, and this new and monstrous growth of evil may be rooted out.” The king asked, “And what good will come of this matter for you?” “For me, perhaps nothing,” replied Anselm, “but something I hope, for God and for thyself.” “Enough!” rejoined the king, “speak no more on this subject.”

Both men disliked one another. William hated Anselm’s maneuvering. Anselm was extremely frustrated by William’s intransigence and went into exile.

William’s Death – Accident or Assassination?

All the accounts of William’s death agree that he was killed by an arrow while hunting in New Forest on August 2, 1100. The most complete account of the day comes from the Anglo-Norman monk, Orderic Vitalis. He wrote that King William dined with the hunting party, which was made up of William’s youngest brother, Henry, Walter Tirel, and Gilbert de Clare and his younger brother, Roger de Clare. Walter Tirel was married to Richard de Clare’s daughter. He had recently arrived in England from France. William had been presented with six arrows by his armorer the night before. Taking four for himself, he gave two to Tirel, saying, “Bon archer, bonnes fleches.” (“To the good archer, the good arrows.”) According to Orderic, William said, “It is only right that the sharpest arrows go to the man who knows how to inflict the deadliest shots.”

William of Malmesbury in his Chronicle of the Kings of the English (1128) described the hunt: “The next day he went into the forest…He was attended by a few persons…Walter Tirel remained with him, while the others were on the chase. The sun was now declining, when the king, drawing his bow and letting fly an arrow, slightly wounded a stag which passed before him…The stag was still running…The king followed it for a long time with his eyes, holding up his hand to keep off the power of the sun’s rays. At this instant, Walter decided to kill another stag. Oh, gracious God! The arrow pieced the king’s breast. On receiving the wound the king uttered not a word; but breaking off the shaft of the arrow where it projected from his body…This accelerated his death. Walter immediately ran up, but as he found him senseless, he leapt upon his horse, and escaped with the utmost speed. Indeed, there were none to pursue him: some helped his flight; others felt sorry for him. The king’s body was placed on a cart and conveyed to the cathedral at Winchester…blood dripped from the body all the way.” What were the sources of William of Malmesbury’s account of King William’s death and Walter Tirel’s flight from the forest? He doesn’t say. He implied that Walter Tirel killed William but didn’t state it.

The Peterborough Abbey’s version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle states that “on the morning after Lammas Day, the king William was shot with an arrow in hunting by a man of his.” Another chronicler, Geoffrey Gaimer stated, “We do not know who shot the king.” Gerald of Wales wrote, “The King was shot by Ranulf of Aquis.” Research into Ranulf of Aquis draws a blank; there is no indication of who he was. Could Gerald of Wales have meant Ralph of Aix, the armorer of King William?

In her 2008 book, King Rufus, The Life and Mysterious Death of King William II of England, Dr. Emma Mason argues that King William was assassinated by a French agent, Raoul d’Equesnes, who was in the household of Walter Tirel. No one knows exactly who the killer was, but most people and historians assume it was Walter Tirel. Could he have killed the king and fled England safely without a plan and accomplices?

Walter Tirel was never charged for the crime and never returned to England. His son was allowed to keep his estates. Abbot Sugar of St. Denis, historian, statesman and confidant of French kings, maintained Walter Tirel was innocent. “It was laid to the charge of a certain noble, Walter Thurold,” Sugar writes, “that he had shot the king with an arrow: but I have often heard him, when he had nothing to fear nor to hope, solemnly swear that on the day in question he was not in the part of the forest where the king was hunting, nor ever saw him in the forest at all.”

Who Benefited from King William’s Death?

1. His brother, Henry, who became King of England three days later.

2. Archbishop Anselm, who returned to Canterbury from exile in France.

3. King Philip I of France – King Henry immediately cancelled King William’s plans for an invasion of France

- The de Clare family – close to King Henry, attained great wealth and prominence.

Missing Clues

- Where were the different members of the hunting party when the king was shot?

2. Who alerted Henry that William had been killed?

3. Why didn’t other members of the hunting party try to help the wounded king?

4. Why wasn’t the fletching of the arrow that killed King William identified?

5. Who assisted Walter Tirel in his escape from New Forest?

6. Why is there no mention of any attempt by Henry to find his brother’s killer?

Dreams of Blood and Death

Medieval people were interested in dreams and attempted to interpret them. Often a dream would be seen as a sign of future events, or a divine warning that someone needed to change their ways. There are many accounts of dreams predicting the death of King William by an arrow. They all occurred just before or the day of the hunt. Was Archbishop Anselm privy to a plot to assassinate King William? Were senior clerics complicit in a plot to replace the king? They could argue that their dreams justified his death as a just punishment from God.

King William II: There are two dreams attributed to the king. In one version, the king dreamed that he was being bled by a surgeon who opened a vein in his arm. A stream of blood spurt into the sky blocking out the sun. The king awoke in terror and called for his servants to stay with him until dawn. In another story from clerical chronicler, William of Malmesbury, William “dreamt that he went to hell and the Devil said to him ‘I can’t wait for tomorrow because we can finally meet in person!’ He commanded a light to be brought and forbade his attendants to leave him.” The king decided to forgo the hunt but changed his mind in the early afternoon when his good spirits returned.

Robert FitzHamon: Anglo-Norman baron and magnate, related to William I and friend to William II – had many ominous dreams in the days leading up to the king’s killing. FitzHamon also reported the dream of a “foreign monk” to the king on the morning of the hunt: The monk has seen the king enter a church, “looking scornfully around the congregation with his usual haughty and insolent air.” He seized the rood (a crucifix) tearing apart its arms and legs. The figure of Christ lost patience and gave King William a kick in the mouth. He fell, and flames and smoke issued from his mouth, putting out the light of the stars. William laughed at FitzHamon’s story, “He is a monk, and dreams for money like a monk: give him this,” handing FitzHamon a hundred shillings.

William Mortain, Earl of Cornwall: Son of William I’s half-brother, Robert of Mortain. While out walking in the woods, the earl encountered a large black hairy goat carrying the figure of the king. The goat spoke to him, saying he was taking the king to his judgement.

Peter de Melvis: He dreamt that he met a rough peasant man in Devonshire bearing a bloody arrow, who said to him, “With this dart your king was killed today.”

Fulchered, Abbot of Shrewsbury: French-born Fulchered delivered a prophetic sermon at Gloucester Abbey (Serlo’s abbey) on August 1, 1100 – the day before William II was killed. “England is allowed to become a heritage trodden under foot by the profane, because the land is full of iniquity. Its whole body is spotted by the leprosy of a universal iniquity, and infected by the disease of sin from the crown of the head to the sole of the feet. Unbridled pride stalks abroad, swelling, if I may say it, above the stars of heaven. Dissolute lust pollutes not only vessels of clay, but those of gold, and insatiable avarice devours all it can lay its hands on. But lo! A sudden change of affairs is threatened. The libertines shall not always bear rule, the Lord God will come to judgement of the open enemies of his spouse, and strike Moab and Edom with the sword of his signal vengeance…The bow of divine vengeance is bent on the reprobate, and the swift arrow taken from the quiver is ready to wound. The blow will soon be struck, but the man who is wise enough to correct his sins will avoid the infliction.”

Serlo, Abbot of Gloucester: Serlo was a Benedictine monk who was Norman by birth and a former chaplain to William I. He had the respect of William II, who described him as “a good abbot and sensible old man.” William was about to set out on the hunt when he received a message from Serlo, informing him of a recent vision one of his monks had experienced. “I saw the Lord Jesus seated on a lofty throne, and the glorious host of heaven, with the company of the saints, standing round. But while, in my ecstasy, I was lost in wonder, and my attention fixed deeply on such an extraordinary spectacle, I beheld a virgin resplendent with light cast herself at the feet of the Lord Jesus, and humbly address to him this petition – ‘O Lord Jesus Christ, the Savior of mankind, for whom Thou didst shed Thy precious blood when hanging on the cross, look now in compassion on Thy people which now groans under the yoke of William. Thou avenger of wickedness, and most just of all men, take vengeance, I beseech Thee, on my behalf, of this William, and deliver me out of his hands; for, as far as lies in his power, he has polluted me, and grievously afflicted me.’ The Lord replied, ‘Be patient and wait awhile, and soon you will be amply revenged of him.’” The King finished reading the message and laughed. “Does Serlo,” he asked, “think that I believe in the visions of every snoring monk? Does it take me for an Englishman, who puts his faith in the dreams of every old woman?”

Prior (Bernard?) of Dunstable: The prior had a dream in which he saw William’s armorer, Ralph of Aix, present a sheaf containing five arrows to the king. The prior felt this boded misfortune but did not tell anyone.

Unknown Monk: While chanting on the morning of William’s death, he saw through his closed eyes a person holding out a paper which was written, “King William is dead.” When he opened his eyes, the person was gone.

Hugh, Abbot of Cluny: St. Hugh, or Hugh the Great, was a powerful and influential leader. He had a personal reputation as a wise and savvy diplomat. Hugh advised Pope Gregory VII in his investiture controversy with Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV. The abbot told Archbishop Anselm he dreamed about King William’s death. In his dream William had been summoned before God and condemned. The king was killed the next day.

Archbishop Anselm of Canterbury: Anselm was in Lyons, France when he received news that King William was dead. In the middle of the night, an “angelic youth” appeared to Brother Adams, Anselm’s guard, and said to him, “Know for certain the controversy between Archbishop Anselm and King William is decided.”

The episode was described in Flores Historiarum (Flowers of History) a chronicle compiled by various hands, but linked to two monks, Roger Wendover and Matthew Paris. The Flowers of History also detailed Anselm’s dream about William’s death and his return to England. “By the impiety and injustice of William Rufus, Anselm, the Archbishop of Canterbury, was driven into exile, and remained there til he saw in a vision of the night that all the saints of England were complaining to the Most High of the tyranny of King William, who was destroying his churches. And God said, “Let Alban, the proto-martyr of the English come hither,” and he gave him an arrow which was on fire, saying, “Behold the death of the man of whom you complain before me.” And the blessed Alban, receiving the arrow, said, “And I will give it to a wicked spirit, an avenger of sins,” and saying this he threw it down to earth, and it flew through the air like a comet. And immediately Archbishop Anselm perceived in the spirit that the king, having been shot by an arrow, died that night. And accordingly, at the first light of the morning, having celebrated mass, he ordered his vestments, and his books, and other movables, to be got in readiness, and immediately set out on his journey to his church. And when he came near it, he heard that King William had been shot by an arrow that very night, and was dead.”

Anselm reputedly wept or sobbed when he received news of King William’s death. The people around him were astonished by his reaction.

Was there a Plot to Kill the King?

Yes, based on the number of dreams and premonitions. I believe Abbot Serlo caught wind of a plot and tried to warn William. Archbishop Anselm may have heard rumors of a plot and started on his way back to England to reclaim his see at Canterbury. I think that Anselm wasn’t directly involved in the assassination, but he didn’t do anything to stop it. The abbots, bishops and other members of the hierarchy may not have known who killed William, but since they believed they would fare better under his younger brother, Henry, justified his death as a divine punishment.

Who Killed the King?

Based on circumstantial evidence and intuition, I believe that it was one of the de Clares with the full knowledge and support of Henry. Walter Tirel was with the king when he was killed, or found the body, and the others told him to flee since he would be blamed. Tirel was never charged since King Henry and the others knew he was innocent.

Further Reading:

My Dear Boy: Gay Love Letters through the Centuries by Rictor Norton (1998) – Best Beloved Brother – The Gay Love Letters of Saint Anselm

King Rufus: The Life and Mysterious Death of William II of England by Dr. Emma Mason (2008)

The Strange Death of William Rufus by C. Warren Hollister (1973)

The Death of the Red King by Paul Doherty (2006)

Does Purgatory exist? Is Hell real? When I was growing up, I thought so. I stopped believing in both places as a young adult; now I’m not so sure.

I grew up being taught to pray for people in Purgatory as well as to light candles and have Masses said for them. The living were responsible for remembering those in Purgatory in prayer and for trying to set them free to get to Heaven.

The biggest reason I stopped believing was the stupidly of the punishment for sin: missing Mass on one Sunday, saying the Lord’s name in vain one time—after a life of goodness—could condemn a person to Hell for eternity. Conversely, a person who lived a mean, cruel, self-centered life could avoid any consequences by one expression of repentance at the end. If God is merciful—and I believe God is—then it seems more measured to consider the whole span of life. God may not follow my logic.

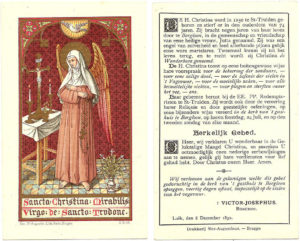

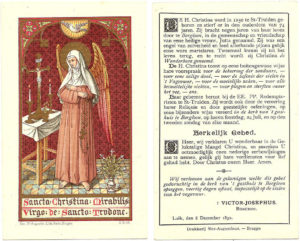

Was Purgatory as a place conceived as a place of purification? Purgatory was a relatively new formal teaching for Christians when St. Christina the Astonishing experienced it in the 12th century; but other experiences of Purgatory were also popularized when she lived.

The idea of purgatory as a process of cleansing dated back to early Christianity as was evident in the writings of St. Augustine and St. Gregory the Great. The 12th century was the heyday of medieval other world-journey narratives such as the account of an Irish knight in “Visio Tnugdali,” and of pilgrims’ tales about St. Patrick’s Purgatory, a cave-like entrance to purgatory on a remote island in Donegal, Ireland.

St. Christina the Astonishing was born in 1135 at Brustem, near Liege, Belgium. She was orphaned as a teenager and worked as a shepherdess. She had two older sisters. Sometime in her early 20s, she suffered a massive stroke or seizure. When people found her in the field, she was limp and unresponsive. Unable to hear a heartbeat or feel breathing, everyone assumed she was dead.

She was carried into church for her funeral Mass in an open coffin. After the Agnes Dei she suddenly sat up and flew up to the rafters “like a bird” and perched there. All the mourners except the priest and her oldest sister fled. Christina said that had taken refuge up there because she could not stand the smell of sinful human bodies. The priest reached out to her and told her to come down. She told him angels had guided her into a dark place where she saw many people she had known in torment. This was Purgatory. Then she was taken to Hell, where she saw other people suffering. Finally, she was taken to Heaven and given a choice: stay in Heave or return to earth to offer penances for those in Hell and Purgatory so they might be released. Her suffering would also help to convert the living. She immediately woke up when she chose to return to life.

After her experience of death and vision of Purgatory, Hell and Heaven Christina felt called to suffer for others so they could be released from suffering. She voluntarily lived in extreme poverty, homeless and dressed in rags. She lived by begging. She often fled to remote areas, climbed trees and rocks. She hid in ovens. Christina avoided human contact as much as possible, saying she couldn’t bear the spiritually stinky smell of sinful people.

Christina also sought out suffering to increase the penance she felt she must endure. People watched her intentionally throw herself into fires and remain there for extended periods of time. She would appear to be in terrible pain, but then would exit the fire completely unharmed. She allowed herself to be attacked and bitten by dogs and would intentionally run through thickets of thorn bushes. In the winter, she would plunge into the freezing Meuse River. The current sometimes carried her downriver to a watermill where the wheel “whirled her around in a manner frightful to behold.” Christina would emerge from all these self-torments bloody but unhurt—no scars, burns or broken bones. Despite a lifetime of abuse and hard living, Christina died at the ripe old age of 74 on July 25, 1224 at the Dominican Monastery at Sint-Truiden (Saint-Trond). She spent the last three years of her life there, and according to the prioress was generally docile and well-behaved.

People had mixed opinions about Christina. Was she insane? Was she possessed? Was she a holy woman and mystic sent to warn people about the fires and pains of Purgatory?

Centuries later, we read regularly about people who have near death experiences and believe they have glimpsed the afterlife. Most of them describe tunnels of light and bliss, but some have described a Purgatory or Hell-like place. We also know now that people who experience a hypoxic-anoxic brain injury can wake to cognitive, physical and psychological changes. This injury appears to be what happened to St. Christina the Astonishing. She most likely had a heart attack or massive stroke and oxygen didn’t reach her brain for several minutes or longer, resulting in a deathlike state and permanent brain damage.

Several saints besides St. Christina have had a vision journey to Purgatory and back. They include St. Catherine of Genoa, St. Lidwina of Schiedam, and St. Maria Faustyna Kowalska, the saint who inspired Divine Mercy Sunday. Several of the “seers” of Medjugorje have visited Purgatory, Heaven and Hell with the Blessed Mother, who regularly sends messages to the seers about these places and the people populating them. The main message is that they need to believe in them, pray and do penance to help the people who are there. There is nothing new or original in these visions. We have seen the same scenes in paintings, stained glass windows, catechism lessons, books and TV.

Jesus mentioned Paradise and Gehenna, but never a place like Purgatory. Was it concocted as a way station for pilgrims on their way home or a course correction for the living? Does Purgatory answer a primal need for a connection to the dead; and prayer and penance a way to commune and express our care and love for them? It is also an outreach to the forgotten—something the Church teaches us to honor in the here and now.

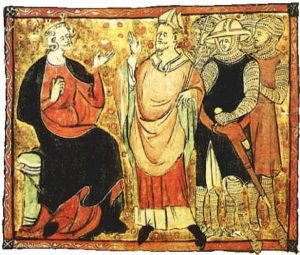

The headline read: “Thomas Becket’s bloody tunic returns to Canterbury 850 years after he died. Vatican to send back historic relic worn by archbishop as he was brutally murdered.” In 2020, Canterbury Cathedral will mark the 850th anniversary of Becket’s assassination, and the 800th anniversary of the creation of his shrine.

Celebrating Becket

Canterbury Cathedral, where Becket was killed on December 29, 1170 following a series of bitter disputes with King Henry II, became a shrine after Pope Alexander III made Becket a saint three years following the murder. It drew thousands of pilgrims (think of Canterbury Tales by Chaucer) until the shrine was destroyed by King Henry VIII in 1538.

Spotting a way to make money and draw visitors, Canterbury Cathedral is set to host a series of celebrations in 2020 to mark the anniversaries, including a joint church service by Catholics and Anglicans.

I wonder how they are going to navigate a potential P.R. nightmare: Archbishop Becket was killed because he refused to permit priests and others claiming clerical status to be tried in the King’s courts for rape, murder, theft and other serious crimes. This sounds a lot like the sex abuse scandals today–cardinals, bishops, church officials and popes refusing to turn criminal clerics over to secular authorities. Their top priority was to shield themselves and their priests from public exposure and civil justice. In the end their stance was about power, privilege and revenues.

The 1964 film, Becket, starring Richard Burton as Becket, and Peter O’Toole as Henry II gave a sympathetic portrayal of Becket as a principled man standing up to civil authority. Three decades of sex abuse scandals in the Catholic Church has ended portrayals of bishops as principled men. Most people today would clap and cheer to see a bishop knocked down. They prefer to rely on civil authorities for justice, not shifty archbishops or opaque canonical courts.

The King’s Friend

Thomas Becket, also known as St. Thomas of Canterbury, was born in London in 1119 or 1120. His parents were both of Norman descent. Becket was a self-made man. Recommended by Theobald of Bec, Archbishop of Canterbury, he was appointed Lord Chancellor in 1153 by King Henry II. They became very close friends. Henry even sent his son and heir, young Henry. to be educated in Becket’s household.

Some clues can be surmised about Becket’s character from stories about him: he was proud, vain, sensitive about his prerogatives and authority, but also warm and protective. He faced his death with courage and resolve. He sought to protect his monks from the knights who came to kill him. Henry’s son said he received more fatherly love from Becket in one day than he did from his father, the king, in a lifetime. Becket was described as dressing lavishly and extravagantly. While riding together through London on a cold winter’s day, King Henry saw a pauper shivering in his rags. He asked Becket if ht would not be charitable to give the man a cloak. Becket agreed that it would. The King grabbed Becket’s expensive fur cloak and a tussle ensued. The King finally succeeded in ripping it away and threw it to the beggar. Becket was very unhappy and offended.

Archbishop of Canterbury

Everything changed in 1162, when Archbishop Theobald of Canterbury died and his seat became vacant. King Henry immediately saw an opportunity to increase his influence over the church by naming his loyal adviser and friend, Thomas Becket, to the highest ecclesiastical post in the land. The pope agreed on his selection. In preparation for his appointment, Becket was ordained a priest on June 1, 1162. The next day he was ordained a bishop, and later that afternoon made Archbishop of Canterbury.

Becket changed on becoming Archbishop of Canterbury. He defended the rights of the church. He exhibited concern for the poor. He became an ascetic. He wore a filthy hair shirt under his vestments. This change is a great mystery, for which none of the chroniclers agree on an answer. Why did Becket evolve from a greedy and luxury-loving man, a loyal chancellor and friend, to a obstinate and contentious churchman? Did he take his appointment seriously? Was it an opportunity to be independently powerful from his friend, King Henry? Or did he really have a spiritual awakening and conversion? I have no answer, but lean toward the idea he found his vocation.

The Benefit of Clergy

The big fissure between King Henry and Archbishop Becket came over “the benefit of clergy” (Privilegium Clericale). When accused of a crime members of the clergy could claim they were outside the jurisdiction of secular courts and be tried in an ecclesiastical court under canon law instead. This usually resulted in a much lighter sentence or punishment. King Henry was determined to increase his control over the church by eliminating this custom. He wanted clerics convicted of serious crimes to be handed over to civil authorities for punishment. The church hierarchy disagreed, arguing that this would undermine the principle of clerical immunity.

Two violent crimes brought the problem to a head. A cleric in the diocese of Worcester was accused of mudering a man in order to rape his young daughter. King Henry ordered the man to be tried in a civil court. Becket intervened, commanding the Bishop of Worcester to put the man in an episcopal prison and not allow royal officials to touch him. In another notorious case, Philip of Bois, a canon of Bedford, was acquitted in the court of the Bishop of Lincoln on the charge of murdering a knight. Pushed by the family of the knight seeking justice, the Sheriff of Bedford attempted to re-open the case in a royal court. He was resisted, and furiously abused by Philip, the Bedford canon. Henry angrily demanded justice on the charge of homicide and on an additional charge of contempt. Becket attempted to solve the problem by banishing Philip for a few years, but the whole affair merely showed the inadequacy of canon law in punishing murderers, rapists and thieves.

The rift between the two men grew. King Henry felt betrayed. Archbishop Becket distrusted the motives of the king. The conflict became bitterly personal. Becket went into exile in France. Henry finally got to Becket through the archbishop’s pride. On May 24, 1170, the king had his son, Henry the Younger, crowned at Canterbury by the Archbishop of York. Becket could not stand the snub to the prestige of his office, and two months later the king and archbishop agreed to a compromise which allowed Becket to return and re-crown Henry’s son in a second ceremony.

While in France, Becket excommunicated the Bishops of Salisbury and Lincoln for their support of the king. He excommunicated the Archbishop of York for leading the first coronation. He refused to absolve them. More conflicts arose, and Henry, exasperated and enraged, uttered the final, fateful words: “Will no one rid me of this turbulent priest? What miserable drones and wretches have I nourished and brought up in my household, who let their lord be treated with such shameful contempt by a low-born cleric!”

Murder in the Cathedral

There are several contemporary accounts of what happened on Tuesday, December 29, 1170. Edward Grim, a clerk from Cambridge who was visiting Canterbury Cathedral gave an eyewitness description. Grim tried to protect Archbishop Becket, and nearly had his arm cut off by one of the knight’s swords. He published his account as Vita S. Thomae (Life of St. Thomas) in 1180.

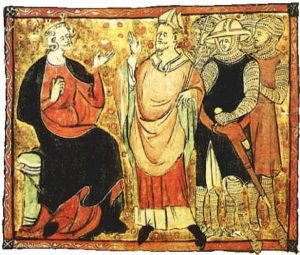

Four knights first entered the cathedral near dusk without weapons. They left them outside by a tree. The knights were escorted in by one of Becket’s monks, Hugh de Horsea, later renamed “Hugh the Evil Clerk.” Becket was informed that four men had arrived to wished to speak with him. He consented to see them. The knights sat for a long time in silence. They confronted Becket and demanded he return with them to Winchester to give an accounting of his actions. He refused. After that the knights retrieved their weapons, and with drawn swords rushed back inside the cathedral for the killing.

“The bell for vespers began to sound, and the archbishop, with his cross borne in front of him, made his way as usual into the cathedral. Hardly had he reached the ascent to the choir than the noise of armed men and the shout of the knights announced that the pursuers were at hand. “Where is the archbishop, where is the traitor!” resounded through the hollow aisles, mingling strangely with the recitation of the psalms in the choir. Becket, hearing this, turned back a few steps, and calmly awaited their approach in the corner of the northern transept before a little altar of St. Benedict. “Here,” he cried, “is the archbishop, no traitor, but a priest of God.” All the clergy present abandoned Becket and fled the cathedral. Only the young clerk from Cambridge, Edward Grim, stayed with him.

The knights surrounded him. “Absolve,” they shouted, “and restore to communion those you have excommunicated and restore their powers to those whom you have suspended.” He answered, “I will not absolve them.”

“With rapid motion they laid sacrilegious hands on him, handling and dragging roughly outside the walls of the church so that there they would slay him or carry him from there as a prisoner, as they later confessed.” Becket struck the incendiary spark. He pushed against the most aggressive of the knights, Sir Reginald FitzUrse, calling him a pimp or panderer, and chiding him saying, “Don’t touch me Rainaldus, you who owe me faith and obedience, you who foolishly follow your accomplices.” The rebuff was too much for an enraged FitzUrse. He swung his sword at Becket, but only knocked off his skullcap. Sir William de Tracy struck next, cutting off the top of Becket’s head, and with the same blow cutting deeply into the arm of young Edward Grim, who was holding Becket protectively. Becket received a second blow on the head from FitzUrse and fell to the stone floor. Then the third knight, Sit Richard de Brito (or Sir Richard de Breton) “inflicted a grave wound on the fallen one, with this blow he shattered the sword on the stone and his crown, which was large, separated from his head so that the blood turned white from the brain yet no less did the brain turned red from the blood; it purpled the appearance of the church with the colours of the lily and the rose, the colours of the Virgin and the Mother and the life and death of the confessor and martyr…” Sir Richard de Brito cried, “Take that, for the love of my lord William, the King’s brother!” when he delivered the fatal blow. William FitzEmpress, the count of Anjou, was Henry’s youngest brother. It was believed by William’s friends that he died of a broken heart after Thomas Becket refused to allow his marriage to Isabel de Warenne, Countess of Survey.

The fourth knight, Sir Hugh de Morville, drove away onlookers who were gathering so the other knights could finish off Becket. The fifth man, Hugh de Horesa, a Canterbury monk, “placed his foot on the neck of the holy priest and precious martyr and, horrible to say, scattered his brains and blood over the floor, exclaiming to the rest, “Let us away, knights; he will rise no more.”

Becket’s body lay on the floor for several hours. Sometime before midnight, Gilbert, the chamberlain, entered the church and tore off a strip of his surplice to cover Becket’s mutilated head. The monks collected the scattered brains and placed the body on a bier in front of the high altar. They also cordoned off the area to block a growing crowd of onlookers, who were tearing off pieces of their garments and dipping them in Becket’s blood.

Cures and Pilgrims

Miracles attributed to Becket’s blood began almost immediately. On the night of the murder, one man took home a piece of bloody cloth to his sick wife who was instantly cured. Reports of similar cures followed in the next few days, mostly involving poor and sick local women.

In the following months, as people came to the cathedral to offer thanks, two monks wrote down the reports of cures. They were Benedict of Peterborough and William of Canterbury. Each man took a different approach. Benedict recorded many cases of poor women, widows and the sick, most of whom lived in the area. William began writing in 1172, when the shrine was becoming fashionable, and focused on wealthy and powerful men. He grouped miracles into types (healing, driving out demons, finding lost items) and the stories became increasingly fantastic. He claimed a Breton woman taught a starling to invoke St. Thomas, and when a kite seized the bird it repeated this phrase and the kite dropped dead, releasing the starling.

The Fate of the Knights

King Henry II did not punish the knights for the murder. He advised them to flee to Scotland. After a short stay, they went to Sir Hugh de Morville’s castle of Knaresborough in Yorkshire. All four were excommunicated by Pope Alexander III on Holy Thursday, March 25, 1171–three months after Becket’s murder.

The knights traveled to Rome and sought an audience with Pope Alexander, who despite their penitence, declared they should be exiled and fight in Jerusalem “in knightly arms in The Temple for 14 years.” After their service was completed, the pope instructed them to visit the holy places barefoot and in hair shirts and live alone for the rest of their lives on the Black Mountain near Antioch, spending their time in vigil, prayer and lamentation. The pope meted out a pretty harsh punishment to the four knights, considering they all had expressed contrition and made amends through various donations and endowments in Becket’s name. No one seems to know exactly what happened to the knights. According to one account, they went to Jerusalem and never returned. They were buried under the portico in the front of the Knights Templar Round Church built on the Temple of Solomon.

In other accounts, Sir Reginald FitzUrse fled to Ireland, where he fathered the McMahon clan. Sir William de Tracy died of leprosy in Italy on the way to the Holy Land. Sir Richard de Brito may have gone to the island of Jersey. Horsea the Evil Clerk disappears from history. Sir Hugh de Morville’s story has two possible endings. He went on pilgrimage to Jerusalem and died in 1173. In 1174 his lands passed to his sister, Maud. He was owner of Pendragon Castle, which according to legend, was built by Uther Pendragon, father of King Arthur. A Hugh de Morville also appears in the service of King Richard I, or Richard the Lionheart as a crusader. De Morville was named the king’s hostage in 1194 when King Richard had been captured by Leopold V, Duke of Austria. This Hugh de Morville provided an Anglo-Norman poem to lay priest and author Ulrich von Zatzikhoven for his romance, Lazelet. Nothing more is heard of de Morville. His sword was said to have passed to Carlisle Cathedral and was displayed for hundreds of years as The Becket Sword. The sword disappeared during the Reformation. Ironically, it was the only sword not used on Becket.

Becket 2020

Canterbury Cathedral will be celebrating the 850 years of Becket’s martyrdom in 2020. They have a special section o on their website – Becket 2020 – detailing events, resources, partner institutions and branding requirements. Becket’s bloody vestments will undoubtedly be the most popular attraction.

2019 and 2020 will see continuing stories in Great Britain and elsewhere on cardinals and bishops who protected sexually abusive priests and “criminous clerks” (to use King Henry’s phrase); or indulged in sinful and criminal behavior themselves with few or no consequences. 800 years ago, King Henry attempted to try clerics charged with serious crimes in civil courts but failed. The cultural and political power of the Catholic Church was too strong.

The ethic of clerical immunity has remained in the institutional Church to this day; but their most potent weapons of excommunication and ban of the sacraments have no impact on today’s public prosecutors, appointed or elected officials. The Catholic Church is not the church of Christendom anymore and has lost much of its moral authority in Europe, as well as the Americas–home to most of the world’s Catholics. The Benefit of Clergy culture has brought the global church to such a crisis ta the pope has had to intervene to save it.

On February 21-24, 2019 Pope Francis will be convening a meeting at the Vatican of the heads of all the bishops’ conferences around the world to discuss the clerical sex abuse scandals and the importance of child protection. One of the action plans will be on the process of turning over bishops and clergy to secular authorities when they have been credibly abuse of abuse, or hindering investigations of abuse. Cardinal Blase J. Cupich of Chicago, one of the meeting’s organizers observed: “Pope Francis is calling for radical reform in the life of the Church, for he understands that this crisis is about the abuse of power and a culture of protection and privilege, which has created a climate of secrecy without accountability for misdeeds,” he said, adding that “all of that has to end.”

I wonder what the martyred Archbishop Becket would have to say about that?

The 17th century in North America was a time and place in a constant state of flux. Cultural clashes, religious struggles and fights for territory spread from pockets to regions. Conflicts in the Old World–England, France, the Netherlands, Ireland, Scotland–struck sparks in New England, Quebec and Ontario. Native nations in this region–the Haudenosaunee Confederacy (Iroquois); Wendat or Wyandot (Huron), Abenaki, Wampanoag, Pequot, Narragansett, Mohegan and Lenape (Delaware) to name a few, leveraged colonists and Europeans in their animosities with each other and settlers. Alliances and advantages were the tidal kind–they shifted back and forth. Sometimes huge waves formed, engulfing everyone in their path before their energy was spent. Anxiety reigned–neighboring people, people who you traded with, even friends, could suddenly turn on you without much warning.

Saving Souls in the New World

Into this frontier paddled French Jesuits and their lay helpers. Their first motive was quite simple: save souls. In those days the dogma was quite clear: the unbaptized went straight to Hell. The rest of their motives for coming to New France were complex: an eagerness to serve in a remote, dangerous place; a desire to introduce their religious and secular ideas and ideals to the native population to improve their lives; and for some, a path to martyrdom. A painful, bloody death would bring them closer to Christ’s passion, and earn a glorious place in the pantheon of martyrs.

The North American Martyrs

Eight men make up the North American Martyrs. They include six Jesuit priests and two lay Jesuit companions. They were martyred between 1642 and 1649 in what is now New York State in the United States and southern Ontario in Canada. The first group, who were killed in the Mohawk village of Ossernenon, included Fr. Isaac Jogues (October 18, 1646) Rene Goupil (September 29, 1642) and Jean de Lalande (October 19, 1646). They were all in their 30s when they died. The remaining six Jesuits were killed by Mohawks in Huronia in 1648-1649. They included Fr. Jean de Brefeuf, Fr. Antoine Daniel, Fr. Gabriel Lalemant, Fr. Charles Garnier, and Fr. Noel Chabanel.

The same missionary spirit they felt has existed throughout the history of the church up to the present day. The beating, rape and murder of Sr. Maura Clarke, a Maryknoll sister and her companions Sr. Ita Ford, Sr. Dorothy Kazel and lay missionary Jean Donovan by soldiers in El Salvador’s military forces mirrors the deaths of the North American Martyrs by beatings, torture, and tomahawks.

Suspicions of Sorcery

One of the reasons these two groups of missionaries were killed was the perception they were introducing ideas and beliefs that would undermine or cause conflict with the existing native culture and power structure. The North American Martyrs were also suspected of sorcery and evil magic.

Jesuit missionaries worked among the Wendat, a people who lived in the Georgian Bay area of Central Ontario. The Wendat were farmers, hunters and traders who lived in villages surrounded by defensive wooden palisades for protection. The missionaries were not universally trusted by the people. Many Wendat believed them to be malevolent shamans or sorcerers who brought death and disease wherever they traveled. In fact, they did: terrible epidemics of smallpox,, flu and other infectious diseases followed in their footsteps and decimated the Wendat and other native peoples. The rivals and enemies of the Wendat, the Haudenosaunee, considered the Jesuits legitimate targets, as the missionaries were generally allied with the Wendat and French. Retaliation for attacks was also a reason for their raids and warfare.

Capture and Death

In 1642, a tribe of the Haudenosaunee, the Mohawks, captured Rene Goupil and Fr. Isaac Jogues as they were traveling from the Jesuit outpost of Sainte-Marie in Ontario to Quebec. They were brought to the Mohawk village of Ossernenon near present day Auriesville, New York. Both men were ritually tortured and mutilated and Goupil was killed. Fr. Jogues was taken in by a Mohawk family. He lived with a kindly “Auntie” and was protected by members of a clan. But his status in the tribe is unclear; he may also have been a slave.

Rescue and Return

Fr. Jogues was eventually rescued by Arendt Van Corlaer, a local Dutch official, and Rev. Johannes Megapolensis, a Dutch Reform minister. He returned to France for several years but then sailed back to Quebec. In 1646 Fr. Jogues and Jean de Lalande, a “donne” or lay Jesuit, were killed during during his second peace mission to Ossernenon. During his first peace mission to Ossernenon, Jogues was given permission by the clan leaders to establish a mission. Before he left for Quebec in June 1646 to gather supplies and helpers to build the mission, Fr. Jogues left a black box with his vestments, books and items. The black box generated suspicion and fear. Illness and crop failure plagued Ossernenon that summer and fall, and an evil spirit in the black box was blamed.

On October 14, 1646 Fr. Jogues, Lalande and a Wendat companion were ambushed a few days walk from Ossernenon. They arrived in the village on October 17 to await their fate. Members of the Bear Clan wanted to kill Jogues, the Wolf and Turtle Clans were against his death. Jogues was invited to a Bear Clan longhouse, but his Auntie counseled him against going. He went anyway and was tomahawked shortly after he entered the longhouse. Lalande heard the commotion and knew Jogues had been killed. Against the advice of the Auntie, he went to recover the body and whatever Jogues had carried with him. He was also killed.

Shrine of the North American Martyrs

Ossernenon, the site of the three Jesuits’ killings, is now known as the Shrine of Our Lady of Martyrs. It is also called the National Shrine of the North American Martyrs. Some archaeologists have recently disputed the location of Ossernenon, placing it nine miles to the west. However, on the shrine site there are signs indicating where the prisoners ran the gauntlet on their arrival from the river below; and the ravine where Rene Goupil’s body was tossed after two warriors killed him. The site is also the reputed birthplace of St. Kateri Tekakwitha. Born in 1656, she was the daughter of a Wendat captive and a Mohawk chieftain. She must have heard stories about the Jesuits growing up.

The World in Which They Lived

I traveled to Ossernenon/Auriesville last month to visit the martyrdom shrine and site. I wanted to sort out my feelings for the missionaries and see where they had lived out their faith and met their death. I first tried to see them in the context of their time. In the 17th century France, England and the Netherlands were fighting and agitating with one another all over the world to stake out riches, land and trading claims. The plague was still widespread in Europe, along with syphilis and other diseases picked up and carries by armies and traders. Thousands of witches were burned at the stake or hanged; the fear of the supernatural fanned by public hysteria over disease, crop failures and anxiety over the future. The reverberations and rivalries between Catholics and Protestants–the Reformation and the Catholic Revival–and subsequent clashes between competing Protestant ideologies were still being felt. Finally, there was a great movement of peoples in response to all these events–either to escape or take financial advantage of them.

The native nations of North America were impacted and changed by their contact with Europeans. They valued the European-made goods, and the increased territorial dominion from trade, firearms and military alliances. They also experienced an inflow of new religious ideas and observances as missionaries made their way to villages following the paths of traders and explorers.

There was an unflinchingly cruel aspect to the age. The native nations ritually tortured and maimed enemy captives; some of them were burned to death taking hours to die. Men, women and children of all ages would be tomahawked and scalped. As policy or retribution, Europeans and colonists annihilated whole villages. Their indiscriminate attacks often fell on villages and native leaders that had pledged peace and good will. Whites also killed for scalp bounties and introduced the first germ warfare by giving smallpox infected blankets to the natives, killing or sickening and scarring everyone. Colonists became accustomed to warriors and their families visiting or living close by to their settlements. The encounters could be friendly, uneasy or hostile.

Who Were the Martyrs?

Who were the three Ossernenon martyrs? Rene Goupil had aspired to be a Jesuit priest but was not accepted because he was deaf. Instead, he became a donne or lay Jesuit and volunteered to go to Quebec to help the missionaries as a physician. After hearing Fr. Jogues describe the great need for medical care in Huronia, he agreed to accompany him. During the voyage he was captured by the Mohawks and brought to Ossernenon. In what Fr. Jogues described as “an excess of devotion and love of the cross,” Rene Goupil made the sign of the cross over a Mohawk boy. Unaware of the meaning of this gesture the boy’s grandfather thought it was evil magic, and sent two warriors to kill him. Goupil either ignored or was not in the country long enough to understand that his blessing would be interpreted as an attempt by an evil shaman to betwitch a small child. Fr. Jogues describes what happened:

“One day, then, we went out of the village to obtain a little solace for our stricken souls and to pray more suitably with less disturbance. Two young men came after us to tell us that we must return to the house. I had some premonition of what was going to happen, and said to him, “My dearest brother, let us commend ourselves to our Lord and our good Mother, Mary. I think these people have some evil plan.” We had offered ourselves to the Lord shortly before with much love, beseeching him to receive our lives and our blood and unite them with his life and his Blood for the salvation of these poor natives. Accordingly, we returned to the village reciting our rosary, of which we had already said four decades. We stopped near the gate of the village to see what they might say to us. One of the two young Iroquois then drew out a hatchet which he had concealed under his blanket and struck Rene, who was in front of him. He fell motionless, his face to the ground, pronouncing the holy name of Jesus. At the blow, I turned around and saw the bloody hatchet. I knelt down to receive the blow that would unite me to my dear companion, but, as they hesitated, I rose again and ran to the dying man who was not far from me. They then struck him two blows on the head with the hatchet, which killed him, but not before I had given him absolution.”

What kind of person was Fr. Isaac Jogues? He was personally brave. He ran to the aid of his dying companion; and during one attack in Huronia he left a good hiding place to aid and comfort his fellow voyagers. Having faced death and torture on his first trip to North America, he left the safety of France to return to Quebec. He was single-minded in his passion for the salvation of souls. He loved the aloneness in the forest, even though supernatural forces were present: “How often on the stately trees if Ossernenon did I carve the most Sacred name of Jesus so that seeing it the demons might take to flight, and hearing it they might tremble with fear.” “The village was a prison to me. I avoided being seen. I loved the quiet, lonely places, in the solitude of which I begged God that he should not disdain to speak with his servant, that he should give me strength in the midst of these fearful trials.”

Did he have a death wish? As I walked along the Shrine’s paths and in the Ravine I couldn’t decide if he actively sought martyrdom for glory; or he wanted to experience suffering as a means of mystical union with Christ; or both. He might have also desired to validate his missionary work with martyrdom, since the French priests made so few converts and were generally unsuccessful in their missionary efforts.

Of the three Jesuits martyred in New York, I liked Jean de Lalande the best. His motives were the clearest and least complicated. He wanted to serve, was aware of danger and accepted it. I also imagine he had a keen curiosity and interest to see the wilderness and meet its people. Lalande arrived in Quebec as a lay brother. He accompanied Fr. Jogues to Ossernenon, offering his skills as a woodworker and woodsman during the journey and to help build the new mission. Lalande was killed when he tried to retrieve Jogues’ body. A brave gesture, since he probably knew he would be killed in the attempt.

What Did the Wendats and Mohawks Think?

They did not treat the French Jesuits any differently then they did their own in war and peace. The priests did not get the deference as clerics they would have expected in France and Quebec. They were expected to do physical labor and contribute to the welfare of the longhouse. I looked out over the ancient village site and marveled again at the hospitality and tolerance the Mohawks granted to the strangers in their midst. They attempted to integrate them into their own culture, fed them, and attempted to protect them at the cost of their own physical safety. The Jesuit missionaries were clumsy and cloddish and did not pick up on social cues or listen to the advice their “Auntie” and other people tried to give them. They were killed because some leaders believed they brought harm or disease to the people by their magic gestures and items used in devotions or Mass. The Jesuits were in the vanguard of Europeans who infected and wiped out whole villages. There might have been quite a different outcome if the native nations had not been wiped out by diseases to which Europeans were immune, but lethal to the native people.

How the Martyrs’ Story was Revived

As the French and British were beaten back into Canada and Europe the stories of the Jesuits killed in Ossernenon faded away. They weren’t American colonists and they were Catholic, so theirs wasn’t a history that was preserved. That changed when Fr. John J. Wynne, S.J. took an interest in them.

Widely recognized as an editor, educator and intellectual, Fr. Wynne (1859-1948) founded the Jesuit periodical America (1909) and the Catholic Encyclopedia. From the 1890s to his death in 1948, Fr. Wynne became a big promoter of these “American” martyrs so that immigrant Catholics might be perceived more readily as “real” Americans by the WASP elite in power.

The canonization of Fr. Isaac Jogues, Rene Goupil and Jean de Lalande in 1930 by Pope Pius XII gave the United States its first saints and martyrs. That provided some stature to the church in America, which was politically powerless in the Vatican and always suspect in matters of doctrinal purity. (“Americanism” was one of the Modernisms that infuriated the late 19th and early 20th century papacy.)

But devotion to the North American Martyrs never caught on in the United States. Immigrant Catholics didn’t warm to them since their rural Auriesville, NY shrine was hundreds of miles away from the struggles of urban Catholic ghettos. Most of the inhabitants were other tribes: Irish, German, Italian, Polish. Catholic colonists didn’t venerate them either because Jesuits like Fr. Sebastien Rale incited and led the Abenaki and others to attack settlers in New England. As the descendant of Maine settlers who were victimized by the French and their tribal allies, I was glad to read he was eventually killed and scalped by colonial troops.

Personal Reflections

I visited the Auriesville shrine last month shortly before it closed for the winter. I expected to scoff and came away a fan. I liked its rustic simplicity. I liked how the builders how incorporated the wooden palisades of the native people and French into the altar design. I especially liked the wooden chapel dedicated to St. Kateri Tekakwitha, where only screens separated worshipers from nature.

It is a shame that more people don’t visit the shrine. There is a lot to learn, and feel, and be inspired by the faith of the Jesuit martyrs and St. Kateri Tekakwitha. They sought God among the people they encountered, the rivers and lakes, forests and fields, and that sustained them. That makes them true North Americans.

We can be equally inspired by the Mohawk and the Wendats’ courage and loyalty, their patience and hospitality, allowing strangers and migrants into their homelands to preach, trade and settle. Their generosity cost many of them their lives, their lands, their way of life, in fact, everything. Some of them died for their new Christian faith. They should also be honored as saints and martyrs. I thought of them all with respect and gratitude, as I said a quiet prayer toward the end of a warm afternoon.

Additional Reading

The Jesuit Martyrs of North America: Isaac Jogues, John De Brebeuf, Gabriel Lalemant, Noel Chabanel, Anthony Daniel, Charles Garnier, Rene Goupil, John Lalande by John J. Wynne, S.J

The Death and Afterlife of the North American Martyrs by Emma Anderson

The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents (accounts of missionary activities from 1610-1701)

I stumbled on the name of Tanchelm thumbing through my copy of Magnificat. He was featured prominently in a story about St. Evermod, a bishop who died in 1178. Evermod was inspired to devote his life to God after hearing a sermon given by Saint Norbert, the founder of the Premonstratensian order. Evermod became a priest of Norbert’s order and was chosen to accompany him on a jorney to Antwerp to counter the followers of Tanchelm, an itinerant preacher who had been murdered a decade before by a priest.

“The city was at the time in a state of ferment due to the heretical preaching of Tanchelm,” the Magnificat huffed, “a man of depraved morals who attacked the hierarchy and the church’s teaching on the sacraments, particularly the Holy Eucharist.”

Evermod remained in Antwerp to combat Tanchelm’s “propaganda.” His apostolic zeal earned him an eventual sainthood, as it did St. Norbert, who is often pictured with a foot on Tanchelm holding a monstrance. Tanchelm’s heresy were his attacks on the doctrine of the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist.

Who was Tanchelm that he made two bishops saints in their attempts to overcome his preaching?