Becket 2020

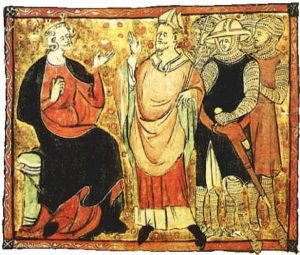

The headline read: “Thomas Becket’s bloody tunic returns to Canterbury 850 years after he died. Vatican to send back historic relic worn by archbishop as he was brutally murdered.” In 2020, Canterbury Cathedral will mark the 850th anniversary of Becket’s assassination, and the 800th anniversary of the creation of his shrine.

Celebrating Becket

Canterbury Cathedral, where Becket was killed on December 29, 1170 following a series of bitter disputes with King Henry II, became a shrine after Pope Alexander III made Becket a saint three years following the murder. It drew thousands of pilgrims (think of Canterbury Tales by Chaucer) until the shrine was destroyed by King Henry VIII in 1538.

Spotting a way to make money and draw visitors, Canterbury Cathedral is set to host a series of celebrations in 2020 to mark the anniversaries, including a joint church service by Catholics and Anglicans.

I wonder how they are going to navigate a potential P.R. nightmare: Archbishop Becket was killed because he refused to permit priests and others claiming clerical status to be tried in the King’s courts for rape, murder, theft and other serious crimes. This sounds a lot like the sex abuse scandals today–cardinals, bishops, church officials and popes refusing to turn criminal clerics over to secular authorities. Their top priority was to shield themselves and their priests from public exposure and civil justice. In the end their stance was about power, privilege and revenues.

The 1964 film, Becket, starring Richard Burton as Becket, and Peter O’Toole as Henry II gave a sympathetic portrayal of Becket as a principled man standing up to civil authority. Three decades of sex abuse scandals in the Catholic Church has ended portrayals of bishops as principled men. Most people today would clap and cheer to see a bishop knocked down. They prefer to rely on civil authorities for justice, not shifty archbishops or opaque canonical courts.

The King’s Friend

Thomas Becket, also known as St. Thomas of Canterbury, was born in London in 1119 or 1120. His parents were both of Norman descent. Becket was a self-made man. Recommended by Theobald of Bec, Archbishop of Canterbury, he was appointed Lord Chancellor in 1153 by King Henry II. They became very close friends. Henry even sent his son and heir, young Henry. to be educated in Becket’s household.

Some clues can be surmised about Becket’s character from stories about him: he was proud, vain, sensitive about his prerogatives and authority, but also warm and protective. He faced his death with courage and resolve. He sought to protect his monks from the knights who came to kill him. Henry’s son said he received more fatherly love from Becket in one day than he did from his father, the king, in a lifetime. Becket was described as dressing lavishly and extravagantly. While riding together through London on a cold winter’s day, King Henry saw a pauper shivering in his rags. He asked Becket if ht would not be charitable to give the man a cloak. Becket agreed that it would. The King grabbed Becket’s expensive fur cloak and a tussle ensued. The King finally succeeded in ripping it away and threw it to the beggar. Becket was very unhappy and offended.

Archbishop of Canterbury

Everything changed in 1162, when Archbishop Theobald of Canterbury died and his seat became vacant. King Henry immediately saw an opportunity to increase his influence over the church by naming his loyal adviser and friend, Thomas Becket, to the highest ecclesiastical post in the land. The pope agreed on his selection. In preparation for his appointment, Becket was ordained a priest on June 1, 1162. The next day he was ordained a bishop, and later that afternoon made Archbishop of Canterbury.

Becket changed on becoming Archbishop of Canterbury. He defended the rights of the church. He exhibited concern for the poor. He became an ascetic. He wore a filthy hair shirt under his vestments. This change is a great mystery, for which none of the chroniclers agree on an answer. Why did Becket evolve from a greedy and luxury-loving man, a loyal chancellor and friend, to a obstinate and contentious churchman? Did he take his appointment seriously? Was it an opportunity to be independently powerful from his friend, King Henry? Or did he really have a spiritual awakening and conversion? I have no answer, but lean toward the idea he found his vocation.

The Benefit of Clergy

The big fissure between King Henry and Archbishop Becket came over “the benefit of clergy” (Privilegium Clericale). When accused of a crime members of the clergy could claim they were outside the jurisdiction of secular courts and be tried in an ecclesiastical court under canon law instead. This usually resulted in a much lighter sentence or punishment. King Henry was determined to increase his control over the church by eliminating this custom. He wanted clerics convicted of serious crimes to be handed over to civil authorities for punishment. The church hierarchy disagreed, arguing that this would undermine the principle of clerical immunity.

Two violent crimes brought the problem to a head. A cleric in the diocese of Worcester was accused of mudering a man in order to rape his young daughter. King Henry ordered the man to be tried in a civil court. Becket intervened, commanding the Bishop of Worcester to put the man in an episcopal prison and not allow royal officials to touch him. In another notorious case, Philip of Bois, a canon of Bedford, was acquitted in the court of the Bishop of Lincoln on the charge of murdering a knight. Pushed by the family of the knight seeking justice, the Sheriff of Bedford attempted to re-open the case in a royal court. He was resisted, and furiously abused by Philip, the Bedford canon. Henry angrily demanded justice on the charge of homicide and on an additional charge of contempt. Becket attempted to solve the problem by banishing Philip for a few years, but the whole affair merely showed the inadequacy of canon law in punishing murderers, rapists and thieves.

The rift between the two men grew. King Henry felt betrayed. Archbishop Becket distrusted the motives of the king. The conflict became bitterly personal. Becket went into exile in France. Henry finally got to Becket through the archbishop’s pride. On May 24, 1170, the king had his son, Henry the Younger, crowned at Canterbury by the Archbishop of York. Becket could not stand the snub to the prestige of his office, and two months later the king and archbishop agreed to a compromise which allowed Becket to return and re-crown Henry’s son in a second ceremony.

While in France, Becket excommunicated the Bishops of Salisbury and Lincoln for their support of the king. He excommunicated the Archbishop of York for leading the first coronation. He refused to absolve them. More conflicts arose, and Henry, exasperated and enraged, uttered the final, fateful words: “Will no one rid me of this turbulent priest? What miserable drones and wretches have I nourished and brought up in my household, who let their lord be treated with such shameful contempt by a low-born cleric!”

Murder in the Cathedral

There are several contemporary accounts of what happened on Tuesday, December 29, 1170. Edward Grim, a clerk from Cambridge who was visiting Canterbury Cathedral gave an eyewitness description. Grim tried to protect Archbishop Becket, and nearly had his arm cut off by one of the knight’s swords. He published his account as Vita S. Thomae (Life of St. Thomas) in 1180.

Four knights first entered the cathedral near dusk without weapons. They left them outside by a tree. The knights were escorted in by one of Becket’s monks, Hugh de Horsea, later renamed “Hugh the Evil Clerk.” Becket was informed that four men had arrived to wished to speak with him. He consented to see them. The knights sat for a long time in silence. They confronted Becket and demanded he return with them to Winchester to give an accounting of his actions. He refused. After that the knights retrieved their weapons, and with drawn swords rushed back inside the cathedral for the killing.

“The bell for vespers began to sound, and the archbishop, with his cross borne in front of him, made his way as usual into the cathedral. Hardly had he reached the ascent to the choir than the noise of armed men and the shout of the knights announced that the pursuers were at hand. “Where is the archbishop, where is the traitor!” resounded through the hollow aisles, mingling strangely with the recitation of the psalms in the choir. Becket, hearing this, turned back a few steps, and calmly awaited their approach in the corner of the northern transept before a little altar of St. Benedict. “Here,” he cried, “is the archbishop, no traitor, but a priest of God.” All the clergy present abandoned Becket and fled the cathedral. Only the young clerk from Cambridge, Edward Grim, stayed with him.

The knights surrounded him. “Absolve,” they shouted, “and restore to communion those you have excommunicated and restore their powers to those whom you have suspended.” He answered, “I will not absolve them.”

“With rapid motion they laid sacrilegious hands on him, handling and dragging roughly outside the walls of the church so that there they would slay him or carry him from there as a prisoner, as they later confessed.” Becket struck the incendiary spark. He pushed against the most aggressive of the knights, Sir Reginald FitzUrse, calling him a pimp or panderer, and chiding him saying, “Don’t touch me Rainaldus, you who owe me faith and obedience, you who foolishly follow your accomplices.” The rebuff was too much for an enraged FitzUrse. He swung his sword at Becket, but only knocked off his skullcap. Sir William de Tracy struck next, cutting off the top of Becket’s head, and with the same blow cutting deeply into the arm of young Edward Grim, who was holding Becket protectively. Becket received a second blow on the head from FitzUrse and fell to the stone floor. Then the third knight, Sit Richard de Brito (or Sir Richard de Breton) “inflicted a grave wound on the fallen one, with this blow he shattered the sword on the stone and his crown, which was large, separated from his head so that the blood turned white from the brain yet no less did the brain turned red from the blood; it purpled the appearance of the church with the colours of the lily and the rose, the colours of the Virgin and the Mother and the life and death of the confessor and martyr…” Sir Richard de Brito cried, “Take that, for the love of my lord William, the King’s brother!” when he delivered the fatal blow. William FitzEmpress, the count of Anjou, was Henry’s youngest brother. It was believed by William’s friends that he died of a broken heart after Thomas Becket refused to allow his marriage to Isabel de Warenne, Countess of Survey.

The fourth knight, Sir Hugh de Morville, drove away onlookers who were gathering so the other knights could finish off Becket. The fifth man, Hugh de Horesa, a Canterbury monk, “placed his foot on the neck of the holy priest and precious martyr and, horrible to say, scattered his brains and blood over the floor, exclaiming to the rest, “Let us away, knights; he will rise no more.”

Becket’s body lay on the floor for several hours. Sometime before midnight, Gilbert, the chamberlain, entered the church and tore off a strip of his surplice to cover Becket’s mutilated head. The monks collected the scattered brains and placed the body on a bier in front of the high altar. They also cordoned off the area to block a growing crowd of onlookers, who were tearing off pieces of their garments and dipping them in Becket’s blood.

Cures and Pilgrims

Miracles attributed to Becket’s blood began almost immediately. On the night of the murder, one man took home a piece of bloody cloth to his sick wife who was instantly cured. Reports of similar cures followed in the next few days, mostly involving poor and sick local women.

In the following months, as people came to the cathedral to offer thanks, two monks wrote down the reports of cures. They were Benedict of Peterborough and William of Canterbury. Each man took a different approach. Benedict recorded many cases of poor women, widows and the sick, most of whom lived in the area. William began writing in 1172, when the shrine was becoming fashionable, and focused on wealthy and powerful men. He grouped miracles into types (healing, driving out demons, finding lost items) and the stories became increasingly fantastic. He claimed a Breton woman taught a starling to invoke St. Thomas, and when a kite seized the bird it repeated this phrase and the kite dropped dead, releasing the starling.

The Fate of the Knights

King Henry II did not punish the knights for the murder. He advised them to flee to Scotland. After a short stay, they went to Sir Hugh de Morville’s castle of Knaresborough in Yorkshire. All four were excommunicated by Pope Alexander III on Holy Thursday, March 25, 1171–three months after Becket’s murder.

The knights traveled to Rome and sought an audience with Pope Alexander, who despite their penitence, declared they should be exiled and fight in Jerusalem “in knightly arms in The Temple for 14 years.” After their service was completed, the pope instructed them to visit the holy places barefoot and in hair shirts and live alone for the rest of their lives on the Black Mountain near Antioch, spending their time in vigil, prayer and lamentation. The pope meted out a pretty harsh punishment to the four knights, considering they all had expressed contrition and made amends through various donations and endowments in Becket’s name. No one seems to know exactly what happened to the knights. According to one account, they went to Jerusalem and never returned. They were buried under the portico in the front of the Knights Templar Round Church built on the Temple of Solomon.

In other accounts, Sir Reginald FitzUrse fled to Ireland, where he fathered the McMahon clan. Sir William de Tracy died of leprosy in Italy on the way to the Holy Land. Sir Richard de Brito may have gone to the island of Jersey. Horsea the Evil Clerk disappears from history. Sir Hugh de Morville’s story has two possible endings. He went on pilgrimage to Jerusalem and died in 1173. In 1174 his lands passed to his sister, Maud. He was owner of Pendragon Castle, which according to legend, was built by Uther Pendragon, father of King Arthur. A Hugh de Morville also appears in the service of King Richard I, or Richard the Lionheart as a crusader. De Morville was named the king’s hostage in 1194 when King Richard had been captured by Leopold V, Duke of Austria. This Hugh de Morville provided an Anglo-Norman poem to lay priest and author Ulrich von Zatzikhoven for his romance, Lazelet. Nothing more is heard of de Morville. His sword was said to have passed to Carlisle Cathedral and was displayed for hundreds of years as The Becket Sword. The sword disappeared during the Reformation. Ironically, it was the only sword not used on Becket.

Canterbury Cathedral will be celebrating the 850 years of Becket’s martyrdom in 2020. They have a special section o on their website – Becket 2020 – detailing events, resources, partner institutions and branding requirements. Becket’s bloody vestments will undoubtedly be the most popular attraction.

2019 and 2020 will see continuing stories in Great Britain and elsewhere on cardinals and bishops who protected sexually abusive priests and “criminous clerks” (to use King Henry’s phrase); or indulged in sinful and criminal behavior themselves with few or no consequences. 800 years ago, King Henry attempted to try clerics charged with serious crimes in civil courts but failed. The cultural and political power of the Catholic Church was too strong.

The ethic of clerical immunity has remained in the institutional Church to this day; but their most potent weapons of excommunication and ban of the sacraments have no impact on today’s public prosecutors, appointed or elected officials. The Catholic Church is not the church of Christendom anymore and has lost much of its moral authority in Europe, as well as the Americas–home to most of the world’s Catholics. The Benefit of Clergy culture has brought the global church to such a crisis ta the pope has had to intervene to save it.

On February 21-24, 2019 Pope Francis will be convening a meeting at the Vatican of the heads of all the bishops’ conferences around the world to discuss the clerical sex abuse scandals and the importance of child protection. One of the action plans will be on the process of turning over bishops and clergy to secular authorities when they have been credibly abuse of abuse, or hindering investigations of abuse. Cardinal Blase J. Cupich of Chicago, one of the meeting’s organizers observed: “Pope Francis is calling for radical reform in the life of the Church, for he understands that this crisis is about the abuse of power and a culture of protection and privilege, which has created a climate of secrecy without accountability for misdeeds,” he said, adding that “all of that has to end.”

I wonder what the martyred Archbishop Becket would have to say about that?