|

I had the Sirius station tuned to the 60s channel when Dusty Springfield’s song, “I Only Want to Be With You” came on. “I don’t know what it is that makes me love you so,” she sings. “I only know I never want to let you go. ‘Cause you started something, oh, can’t you see? That ever since we met you’ve had a hold on me. It happens to be true, I only want to be with you.” I remembered during the song that Dusty Springfield was supposed to be bisexual; “Son of a Preacher Man” was another one of her big hits. When I got home I decided to google Dusty Springfield and see what became of her. Not only was Dusty Springfield not bisexual—she was a lesbian—she was in the midst of a torrid affair with a woman in Memphis when she recorded “Son of a Preacher Man.” Dusty Springfield was one of the most successful female British singers of the 1960s, with a half dozen singles in the top 20. “You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me,” (1966) was her biggest hit in the U.S. and the U.K.

“There is a sadness there in my voice. I was born with it. Sort of melancholy. Comes with being Irish-Scottish. Melancholy and mad at the same time.” – Dusty Springfield

“My sexuality has never been a problem to me but I think it has been for other people.” – Dusty Springfield

EARLY DAYS

Dusty Springfield was born Mary Catherine Isabel Bernadette O’Brien in London, England on April 16, 1939. Her mother was Irish and her father was Scots-Irish. She was a tomboy growing up, and given the name “Dusty” playing football (soccer) with the boys. She attended an all-girls school, St. Anne’s Convent School in Enfield, London. The nuns predicted that the shy girl was going to become a librarian. As a teen, Dusty had short auburn hair and glasses. She credited the school with her first “blues” performance during a school assembly. After she left at 16, Mary O’Brien recreated herself as “Dusty Springfield,” a glamorous blond with make-up, teased hair and mod outfits.

In the early years of her career Dusty remained a practicing Catholic. The tour bus stopped so she could go to confession or attend Mass. But as the Sixties progressed, the practice of her faith diminished, and she began her long struggle with alcohol, self-harm, and violence in her relationships. She was eventually diagnosed as suffering from bipolar disorder in addition to alcoholism.

Growing up, Dusty knew she was attracted to girls. Her first crush was on one of the nuns. She told Sue Cameron, one of her lovers, that she would watch a girl who lived across the street get undressed in front of the window. Her discovery of her lesbianism led to internal conflicts with her Irish Catholic upbringing, which she never resolved. Most Catholic lesbians and gays could not reconcile their sexuality and faith in the 1960s, and it is still a struggle today. To be one, we had to hide the other. This lack of authenticity and wholeness affected every part of Dusty’s life. Her inability to talk about that part of herself and her relationships produced terrible conflict and pain. For many years she managed it by drinking, drug use, and transient affairs and relationships, and the ever-present cloud of guilt and shame.

CAREER SUCCESS

Dusty had her first woman lover in 1963. In early 1964, her career took off with her first hit single, “I Only Want to Be With You.” Her desire for other women was forbidden in Britain at that time, so like most lesbian and gay artists, she performed for the straight majority but with emotions that were directed to her female partners and pursuits. During her peak, Dusty Springfield ranked among the most successful female performers on both sides of the Atlantic. Her blonde, bouffant hairstyle, heavy eye makeup, evening gowns, and stylized hand gestures, made her an icon of the Swinging Sixties.

She was in the limelight throughout the 1960s with such hits as “I Only Want to Be With You” (1964); “I Just Don’t Know What to Do With Myself” (1964), “You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me” (1965), “All I See is You” (1966), “The Look of Love” (1967), “Breakfast in Bed” (1969) and Son of a Preacher Man (1969). At the same time, Dusty was terrified that her lesbian love life would come to light and her career would be ruined. She also worried about its impact on family, friends and fans. Dusty Springfield hid her lesbianism for years, and used her Catholic upbringing as an excuse: “You have to concentrate on marriage and I’m a Catholic and can’t get divorced,” she said. Dusty was never reported to be in a relationship with a man.

PARADE OF LOVERS

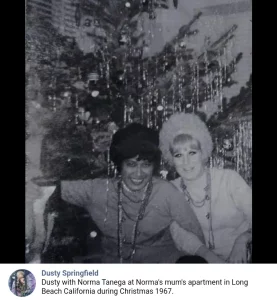

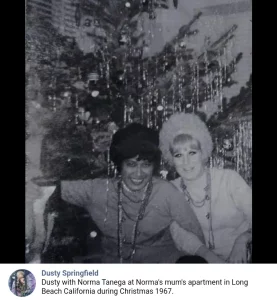

Dusty started churning through women beginning in the mid-sixties. In 1966 Springfield met American singer Norma Tanega, a Mexican-American singer, painter and activist. The couple fought just as hard as they loved. “I can’t tell you how many times I got that phone call at three in the morning,” said one of Dusty’s friends. “Get over here, Cat’s trying to kill me!” (Cat was Norma’s pet name for Dusty). Or, “John, come quick, Norma’s trying to kill me!” Dusty was prone to having flings behind Norma’s back. “I don’t mean that I leap into bed with someone special every night, but my affections are easily swayed and I can be very unfaithful. It’s fun while it’s happening, but it’s not fun afterwards because I’m filled with self-recriminations. The truth is I’m just very easily flattered by people’s attentions, and after a couple of vodkas I’m even more flattered.” She added, “I suppose to say I’m promiscuous is a bit of bravado on my part. I think it’s more thought than action. I’ve been that way ever since I discovered the meaning of the word. I used to go to confession and tell all my impure thoughts.”

Norma Tanega left Dusty in the early 70s when she found their relationship too difficult to sustain. According to Tanega, Dusty “wanted to be straight and she wanted to be a good Catholic, and she wanted to be black.” Springfield owned that while she was brought up Catholic, she no longer went to Mass. “It’s about six years since I made my Easter Duties. My mother’s going to love this. I still think that because I don’t go to Confession I’m going to go to hell but I haven’t done anything evil. I’m just lazy and self-indulgent.”

After Norma, Dusty began a string of on and off relationships, short affairs and one-night stands. From 1972-1978, she saw Faye Harris, an American photojournalist. In the 70s she was linked to the tennis pro Rosie Casals, although Casey’s said they were close friends, not lovers. There was a woman in Australia that shoved Dusty into a hotel fountain during a fight. In 1968, while recording her masterpiece album, “Dusty in Memphis,” she had a torrid affair with a woman named Sandy, drinking and partying so hard that she lost her voice. During the same trip, Dusty got into a fight with Sandy or another woman, which ended up with a TV in the hotel’s swimming pool at 4 am. One of them had picked up the TV and thrown it at the other. It went out the window and down 14 floors into the pool. One woman called the police on Dusty saying she had drugs. “As it happens I know who tipped them off,” she said. “There was a rather hysterical lady who was upset because I didn’t fancy her.”

In 1970 she gave an extremely brave interview to Ray Connolly in London’s Evening Standard, talking about her rumored attraction to women. “There’s one thing that’s always annoyed me, and I’m going to get into something nasty here. But I’ve got to say it because so many people say it to my face. A lot of people say I’m bent, and I’ve heard it so many times that I’ve almost learned to accept it. I don’t go leaping around to all the gay clubs but I can be very flattered. Girls run after me a lot and it doesn’t upset me. It upsets me when people insinuate things that aren’t true. I couldn’t stand to be thought of as a big butch lady. But I know I am perfectly capable of being swayed by a girl as by a boy. More and more people feel that way and I don’t see why I shouldn’t.”

THE OBSCURE YEARS

Dusty Springfield’s honesty came at a price— her popularity waned and she didn’t have a hit single for another 15 years. By the early 70s her stardom was over, and during the next decade and a half she faded into obscurity in LA as her fortune and career ebbed away. In 1972, Dusty had decided to flee the English press and move to California. The move left her short of money and without the support network she had in London. Her alcohol and drug use increased, and she found herself caught in an alcoholic haze that’s still too familiar to lesbians and gays torn between the closet and the need to live honestly. “When I knew Dusty, unfortunately, she was a mess,” said a lesbian business owner in LA who had a brief affair with her. “She was a very fragile, brilliant, special person—the sweetest, nicest person you could ever know. But she was also the most insecure person who ever lived. She was drinking, using, and slitting her wrists. She was so vulnerable.”

In the mid-seventies Dusty plucked up the courage to tell her parents that she was a lesbian—only to have it dismissed as unimportant or a joke. She was devastated by their reaction not to take her seriously. By then, her drug use was out of control, her love life reduced to a string of short-lived affairs, the sales from her recordings were low, and her royalties reduced to a trickle. She was often between stays in rehabs and hospitals. But she had yet to reach her lowest point.

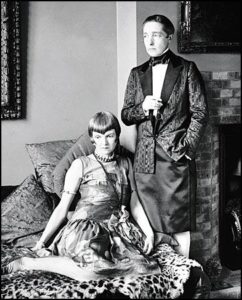

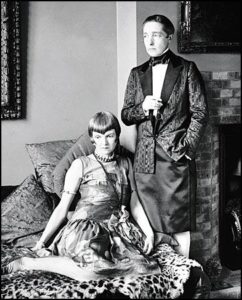

Dusty and Sue Cameron DEMONS, DRUGS AND ALCOHOLISM

In 1974, Springfield’s mother passed away. This brought her to a deep mental low. Her lover, Sue Cameron, said that Springfield would sit on the floor and hallucinate about demons. “She would scream a lot,” Cameron said. “She’s say, “Demons! Demons! They’re coming to get me! – over and over again. “She’d also threaten to harm herself. She said when she cut herself she knew she was alive, because she could feel it.” A succession of psychiatrists confirmed that Dusty was struggling not only with alcoholism but also mental illness; depression and bipolar disorder. She also attempted suicide multiple times. Cameron ended her relationship with Springfield when Dusty chased her with a knife. “I will never know whether she intended to hurt me or not,” Cameron said. “She was laughing at my terror as she came toward me, teasing me by thrusting the knife closer and closer as I backed up. In my heart I think she was playing a sick game that was almost out of her control. I ran out of there to save myself.”

In 1981, Dusty met Carole Pope of Rough Trade, a Toronto-based rock band known for their provocative lyrics. Their 1981 hit, “High School Confidential,” was one of the first explicitly lesbian-themed Top 40 hits in the world.

“She’s a cool blonde scheming bitch, She makes my body twitch. Walking down the corridor. What’s her perfume? Tigress by Faberge. She makes me cream my jeans when she comes my way.”

In 2000, Random House published Pope’s autobiography, Anti Diva. The book detailed Pope’s relationship with Springfield, how they met and first had sex. “My manager, Vicki Wickham, thought that Dusty and I should meet. I heard stories Vicki told about Dusty, and she sounded like a handful, but Vicki believed that you could have any woman you wanted if you put your mind to it. Her mantra, “Every Bird is pullable,” had become part of my philosophy. So, in the fall of 1980 I flew to New York to meet the Queen of the Mods and see her perform at a supper club called the Grand Finale. Vickie came with me. The place was packed with Dusty fanatics and celebs; the audience included Rock Hudson and Helen Reddy, the singer of “I am Woman.”

Carol Pope “My first words were, “Vicki suggested we meet.” Dusty looked at my shyly and smiled. We started to talk and joke around, and within minutes were flirting madly with each other. In the middle of our dance of seduction, Helen Reddy came backstage with her husband. Dusty and I turned to each other and said, after they left, “Why is she married? She seems like a big dyke.”

Some months later, Dusty invited Carol to see her at the Montreal Ritz-Carlton. “I tentatively knocked on the door of Dusty’s suite. She answered, then stepped back into a rococo décor accented with heavy black and gold wallpaper. She seemed shy and unsure, and she was not alone. Her assistant—a girl draped in peals who epitomized the meaning of the word preppy—was introduced as Westchester. She discreetly left the room. Yes, the air was thick with sexual tension. She offered me a drink, and the next thing I knew we were all over each other. We tumbled into bed, half-naked. It was the first time I’d been with an older woman. Dusty had several years on me, and I found the idea very erotic. I fixated on her sensual mouth and unfathomable eyes. The most erotic thing we ever did in bed was this: I would beg Dusty to sing to me. She would put her mouth up to my ear. Then the sound of her voice, so intimate and so close, would wash over me in waves of pure pleasure.

Carol Pope asked Dusty to sing background vocals on a song, “The Sacred and the Profane,” she wrote for Rough Trade’s 1981 album, “For Those Who Think Young.” “Under the influence of Dusty—my twisted Catholic girl—my brain was inundated with images of Fellini films and Catholic morality.”

The hairdresser teaser her coif

With his tail comb

She has the tortured look of a Magnani

Constantly hounded by the paparazzi

The blood of Rome runs through her veins

She’s frightened by her overactive hormones

Mondo Italiano La Dolce Vita

Lust is written all over her face

She loves the smell of danger…

The fury of fallen angels

The aspirations of saints

The sacred and the profane

The relationship between the two started to erode the first time Carol had to take Dusty to the emergency room. “Dusty had taken some pills, coke, and God knows what else.” Carol took the knife out of Dusty’s hands when she started to cut her arms. “I tried to ignore the faded scars on her arms…What kind of self-loathing drove her to it?…Dusty was mainly silent about her past and the origin of her demons.”

“We broke up in LA. I told her I was being torn apart by her behavior. She was lost and I cared deeply about her, but she was fucking up my life. Dusty was very sweet, and resigned to the outcome. A few months before she died, Dusty called Carol to apologize. “She said, “I’m sorry for the way I behaved when we were together. You know I loved you.”

Dusty started to attend Alcoholics Anonymous meetings to help her deal with her drinking. She met actress Teda Bracci at an AA meeting in 1982 and they moved in together in April 1983. Bracci recalled that during a trip to Rome Dusty kissed her on a balcony overlooking the Vatican in defiance of her faith.

The two women wed at the end of 1983, exchanging vows in a backyard ceremony in LA’s San Fernando Valley. A lanky and vivacious brunette, Bracci appeared in some action films: a biker chick in CC & Company with Joe Namath and Ann Margaret; a prison inmate in a few episodes of Falcon Crest, a popular TV soap opera; a female lead in the LA premiere of Hair; and headlined in famous Sunset Strip rock clubs like The Troubadour and the Whiskey-A-Go-Go. The “best lady” at the wedding ceremony said Dusty wore a formal wedding gown, and the other bride wore a pants outfit with a vest and tie. Dusty was trying to stay sober, so anyone who wanted a drink would need to retrieve a bottle of Jack Daniels that hung from a rope outside the bathroom window. “Everyone seemed happy and peaceful that day,” the best lady said.

But like her other relationships, her marriage to Bracci quickly deteriorated into drunken violence. In one incident, Dusty menaced Bracci with a broken cup and slashed her leg. Bracci responded by hitting Dusty repeatedly in the head with a boot.

The last straw came on a day when Dusty was drinking wine and taking Valium. Teda returned to their apartment and the inevitable fight ensued. Bracci hit Springfield in the mouth with a saucepan and her teeth were knocked out. A plastic surgeon was able to patch her up, but damage to her face was permanent. The couple separated, and by 1987 Dusty headed back to Britain and a revival of her musical career.

BREAST CANCER

Dusty recorded several songs with the Pet Shop Boys, including the hits, “What Have I Done to Deserve This,” (1987) and “Nothing Has Been Proved,” (1988). In 1994, during work on her last album, “A Very Fine Love,” Dusty discovered she had breast cancer. Although her initial treatment was successful, the cancer returned and she died on March 2, 1999, in Henley-on-Thames, Oxfordshire, one month short of her 60th birthday. She had a Catholic funeral Mass in St. Mary the Virgin Church. Her casket was brought to the church by a horse-drawn carriage as she requested, and “You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me” was playing as her casket was carried into the church. Hundreds of fans and people from the music business attended her funeral, including ex-lover, Carol Pope.

In her last interview with the New York Times, Dusty said she would be very happy if her life took her back to Ireland. Her brother Tom, honored her wish and scattered a portion of her ashes near her favorite spot, the Cliffs of Moher. The rest of her ashes are buried under a granite marker in St. Mary the Virgin churchyard in Henley.

In the months before her death, Dusty reflected on her life with two of her friends. Lee Everett-Akin was the widow of gay DJ Kenny Everett. Like Dusty, he was raised Catholic, and that formation stayed with him throughout his life. “Being “outed” was one of her greatest fears. She just felt that she would be rejected by everyone if her secret came out. “We had a great affinity around her sexuality because Kenny felt exactly the same way. He was terrified of people finding out. They were very similar people, in that they were both brought up strict Catholics and that brought with it an awful lot of guilt.” Lee added that one of Dusty’s biggest regrets toward the end of her life was that she never settled down with someone. “She had so much love to give, even though she knew she was impossible to live with. She would say, “My life would’ve been so different if I’d had a good relationship.” Lee Everett-Akin had tried to persuade Dusty to write her life story, but Dusty told her she couldn’t remember most of it because of drugs and drinking. “The saddest thing of all,” Everett-Akin said, “was that when she was dying she told me she was embarrassed by her life, by the drinking, the failed relationships. She felt she had made so many mistakes in her life.”

Lee Everett-Akin’s comments echoed those of another close Dusty friend, Simon Bell, who moved in with her for the last 14 months of her life. “There were certain things she was addicted to, like the drink and the drugs and indeed relationships, that she eventually learned she just couldn’t have, said Bell. “She was never totally comfortable with the fact that she was a lesbian. She was very open privately with me but I think her Catholic background stayed with her right to the end and she never completely came to terms with it.”

MY LANGAN LOVE

The anger and the sadness of being a gay or lesbian Catholic always remains. Allies in local parishes, sympathetic clergy, and the large poll numbers of Catholics who believe their LGBT brethren should be treated fairly and respectfully encourage our belief that we truly belong; but the words we heard growing up and as young adults—that we were sick, our desires were twisted, that God, Jesus and the Church were against us—still resonate in our memories and emotions.

Despite all the negativity and doubt, there are times when we feel at home—with a place, in a song, with ourselves. In a YouTube video search of Dusty singing, I chanced on a clip of her performing “My Lagan Love” during a 1967 TV show. It is an old Irish ballad. “People get the idea,” she starts, “that all Irish songs are either “Paddy McGinty’s Goat” or “When Irish Eyes are Smiling,” all those lovely sorts of Hollywood Irish songs. Actually, the most beautiful ones I’ve ever heard are played by a very old gentleman somewhere in Donegal…The song that impressed me most of all was the one I’m going to attempt to sing for you now, called My Lagan Love.” A harper accompanied Dusty, who played an acoustic guitar.

My Lagan Love

Where Lagan streams sing lullabies

There blows a lily fair.

The twilight gleam is in her eye,

The night is on her hair.

And like a lovesick Lennan-shee

She hath my heart in thrall.

No life have I, no liberty,

For Love is Lord of all.

And often when the beetles horn

Has lulled the eve to sleep

I’ll steal into her shelling lorn

And through the doorway creep.

There on the cricket’s singing stone,

She makes the boxwood fire

And sings in sweet and undertone

The song of hearts desire.

Her welcome, like her love for me,

Is from her heart within.

Her warm kiss is felicity

That knows no taint of sin.

And when I stir my foot to go,

‘It’s leaving Love and light,

To feel the wind of longing blow

From out the dark of night.

Dusty’s performance was shy and humble, which made her rendition of the song even more piercingly beautiful. The verses of anticipation, desire, love and longing were authentic; not the covert references to love in her Top 40 hits. Dusty was fully at home and in peace in the love song, and it was beautiful to hear, see and experience.

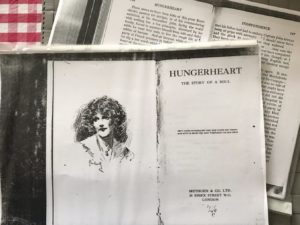

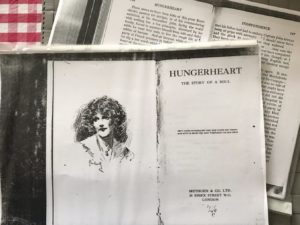

Hungerheart is a lesbian novel written by British author Christabel Marshall under her adopted male name, Christopher St. John. The book was published in 1915 in London by Methuen & Co. The novel is a first-person account of Joanna, “John” Montolivet that follows her search for love and passion. At one point she lives with Sally, a young actress, and they are “happy as a newly married pair, perhaps happier…” Sally decides to marry a man, and Joanna/John finds solace in the arms and bodies of stormy and dramatic women. Eventually she heads for quieter shores, and coverts to Catholicism. Her “friendship” with a young nun fulfills her heart’s hunger. “There are things that can be lived, but not chronicled, and our friendship is one of them,” Joanna/John describes. “Who in the world could understand our moments of union? Who in the cloister either? But they are understood in heaven…Thy love for me is wonderful, passing the love of men.”

Hungerheart never achieved the fame of another book written a decade later by another Catholic lesbian—Radclyffe Hall’s, The Well of Loneliness. Only a few copies of Hungerheart survive in research libraries. For some odd reason, it was not tagged with a homosexual or degenerate label but cataloged as a work about “Catholic spirituality.”

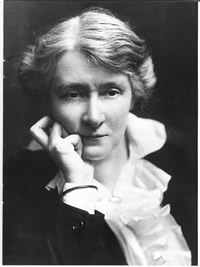

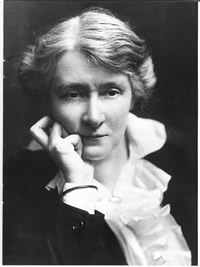

Christabel Marshall The author’s book embodied her voracious love life. Christine Gertrude Marshall a.k.a. Christopher Marie St. John (1871-1960) was an English suffragette, a playwright and writer. After college, Marshall served as secretary to Lady Randolph Churchill and actress Dame Ellen Terry. Marshall became romantically involved with Dame Ellen’s daughter, Edith (Edy) Craig (1869-1947). The two women began living together in 1899. Marshall attempted suicide when Craig accepted a marriage proposal from composer Martin Shaw in 1903. Edith Craig was an actress, director, producer and costume designer.

In 1912 Christabel Marshall converted to Catholicism and took the name, St. John out of affinity with St. John the Baptist. Her friend, Claire Atwood, converted around the same time. Atwood gave Una Troubridge and Radclyffe Hall, another Catholic couple and close friends, a relic of the true cross acquired by her ancestors from a pope. Una put it with candles and flowers in a shrine in her bedroom.

In 1916, artist Claire (Tony) Atwood (1866-1962) moved in with Craig and Marshall. Their menage a trois lasted until Craig’s death in 1947. Una Troubridge used to call them, “Edy and the boys.” They often wore men’s attire to match their male names. “Miss Craig,” wrote Virginia Woolf in her diary, “is a rosy, ruddy ‘personage’ in white waistcoat, with black bow & gold chain loosely knotted.” Marshall wrote rhat the three women “achieved independence within their intimate relationships…working respectively in theatre, art, and literature, and drew creative inspiration and support from one another.”

Edith Craig In 1932, when she was sixty-one, Marshall fell madly in love with Vita Sackville-West, a member of the Bloomsbury Group and a successful poet and writer. Their affair continued for several years and caused huge fights between Marshall and Craig. Atwood unsuccessfully tried to serve as a peacemaker.

In 1935, under her male name, Christopher St. John, Marshall wrote a biography of a distinguished physician, Dr. Christine Murrell, the first female member of the British Medical Association’s Central Council. Titled, “Christine Murrell, M.D., Her Life and Work,” St. John/Marshall wrote the dedication to both of Murrell’s lovers: Honor Bone, M. D. and Marie Lawson, a printer, editor, and tax resister. Like St. John/Marshall, Murrell had a threesome household.

Christabel Marshall/Christopher St. John died in 1960. She is buried next to Claire Atwood at St. John the Baptist’s Church, Small Hythe, England. This is the church where Dame Ellen Terry worshipped and where her funeral Mass was held in 1928. Edith Craig’s ashes were supposed to be buried there as well, but by the time of Marshall’s and Atwood’s deaths, they had been lost. A memorial was placed in the cemetery instead.

Why did so many Anglican clerics, creatives and/or socially prominent gays and lesbians convert to Catholicism in the Victorian and Edwardian eras? The Catholic Church has always been opposed to homosexual sex; but it also has been tolerant of gay sex among its members, including priests, the hierarchy and religious, as long as they were discreet and parroted official teaching in public. At that time, being Catholic was a little naughty, not socially acceptable, and showed a streak of rebellion and independence. Creatives were drawn to the sensuousness, the pageantry, and the mysteries in Catholicism. Catholicism emphasizes the body—the body of Christ in our mouth, the bodies of saints who give themselves up to pain and ecstasy, the homoerotic images found everywhere there are Catholic artists and cathedrals. For women, Catholicism offers many role models of women who lived full and fulfilling lives—without men.

Christopher St. John’s Shrine

Image by Federica Bordoni I went through the entire history of the Conference for Catholic Lesbians (1982-1996) in preparation for this article. In the many letters, notes, articles and comments I read, all the women, regardless of where they were on the spectrum of being Catholic and lesbian, said the same thing: it is very important for me to be who I am. I need to discover all of who I am and would like to do this within a community where I feel safe and understood. I want to be with others where I will feel supported and affirmed in my spiritual and sexual identity. And most of all, I would like to be heard and respected as I talk or pray from the reality of my life.

Susanne S. wrote an op-ed piece for her local paper called, “At Peace with Faith, Sexuality,” For those of us who identify as Catholic and lesbian, it elegantly, and very simply and clearly articulates how we have reconciled what appears on the surface to be a contradiction in terms.

“When I was growing up,” she writes, “I had two passions: one was God, the second was women. Though I have gone through a lot of soul searching with both, neither of those things has changed. I always felt a deep reverence and comfort in the church, and most specifically the Catholic Church. Two years ago, I converted to the Catholic faith, something I had wanted to do all my life. Fortunately, I found a wonderful parish to do this in.

Two years ago, in June, I rediscovered my true sexuality. My sexuality has been a little less easily professed than my faith in God, since, of course, there are so many attitudes that work to repress it. However, through this blessing, I realize life is not worth living unless I can include this part of myself, no more than it is worth living if I cannot profess my faith. All the wonderful feelings I had left behind, along with my ability to write poems, came back to me. I felt whole again. Even without a significant relationship on the horizon, my life has continued to become so much brighter.

To many people my being so intensely Catholic and lesbian at the same time may seem hypocritical. After all, doesn’t the Catholic Church condemn lesbianism and homosexuality in general? And to many feminists and lesbians, Catholicism represents the height of the patriarchy. Yet for me there is no conflict of interest. I recognize the church as an imperfect, human interpretation of Christ’s perfect teachings. I do not believe every word in the Bible is true, or that our pope speaks for God. What I do believe is that God in His/Her infinite wisdom and compassion can bring forth inspiration in spite of prejudice.

The Catholic faith speaks to me, not because it is accurate in hierarchy or rule, but because it feels accurate to me in feeling and in spirit. I also know, unlike many women who are not lesbian and fear the idea of lesbianism, that love as a lesbian is as Godly as heterosexual love is. My feelings are an experience of joy that matches the joy I feel when I watch a priest consecrate the host or present us with a newly baptized child.

I am sorry that there is so much fear and cynicism in the world that some straight people look at my lesbianism as sad and misguided (or worse), and some lesbians look at my love for the Catholic Church as naïve or anti-woman. I hope one day there will be more people who can see the ability to marry their faith with their sexuality. I thank God for both of those parts of me.”

At the 1982 conference at Kirkridge, one of the workshop speakers, Dr. Lorna Hochstein, talked about our relationship with God. She asked us to reflect on the ways in which our relationships with ourselves, with others and with God are affected by the degree to which we acknowledge to ourselves and others that God created us lesbian. Because of that fact we live, love and experience God and the world in a special, particular and complementary way.

Dr. Hochstein told participants that she was not proposing that they disclose their sexual orientation regardless of consequences. But she repeatedly pointed out that invisibility and silence in themselves have consequences: “There are consequences in our relationships with others and thus with God when we choose to keep silent—consequences which affect our understanding of ourselves and the world’s understanding of us. But more important, consequences which affect our understanding and the world’s understanding of God.”

My own relationship with God had been shriveled and bitter for many years. I blamed God for my alcoholism with its horrible pain and loneliness. I wouldn’t set foot in a church I was so angry at God. I was not alone in my feeling of anger: “For the past several months,” a woman wrote, “my personal life has been rather chaotic. And unfortunately, one of the results of that chaos is a great deal of anger directed at God. Despite having physically left the Church, several years ago, that is a new emotion for me. I think the only way I am going to get over that anger is to deal with it directly, a kind of one on one with God. I think all I’m capable of right now is going back to Mass and working through the anger.” We were both estranged from God. The writer’s goal was a one-on-one encounter, but mine was to walk away.

God and I are getting along better these days, although the relationship is not perfect. Over time, and with much searching and self-forgiveness, I have changed the way I see myself, and this has changed how I perceive God. The less harsh and more understanding we are with ourselves and others; the more God has become a close presence of awareness rather than a remote figure of judgment. I can feel God in the beauty of the sun on rippling water in a bay; or in the melody of a hymn everyone enjoys singing together.

One problem lesbian and gay Catholics face is that others attempt to stand between us and God. If we let this happen, we allow ourselves to be marginalized. This is the agenda of particularly conservative or traditionalist Catholics, who are happy to position God in judgment of others whose opinions, values and “lifestyles” are those which traditionalists find distasteful. These conservative Catholics often point to laws in the Bible as justification for how they act and what they say. As for members of the church hierarchy condemning homosexuality, the institution has been discredited by its own hypocrisy on sexual standards and activity, particularly the sexual abuse of children and young people. Bishops as a group have been discredited not only by the behavior of those who protected predator priests, but by all the rest who said and did nothing. By remaining silent and doing nothing, they lost their moral authority.

It is ironic to contemplate that the success of Jesus’ ministry and sacrifice was built on St. Peter’s rejection of legalism. In a dream, God commanded Peter not to exclude others from receiving the “Good News.” “You yourselves know that it is unlawful for a Jew to associate with or to visit a Gentile;” said St. Peter, “but God has shown me that I should not call anyone profane or unclean.” This change of heart by St. Peter changed the whole course of Christianity. In the 1992 book, The Acts of the Apostles,” theologians Luke Timothy Johnson and Daniel J. Harrington, S.J., write that this episode not only signifies a radical change in Peter’s identity as a member of “God’s people,” but also “the implication is that all things God created are declared clean by him, and are not affected by human discriminations.”

There is a lot of anger and sadness present in Catholic lesbians and gay men when it comes to our church. Our sexual orientation had to be kept bottled up and silent if we wanted to continue to belong to our families and church. This inability to talk about our attractions and that part of us produced terrible conflict and pain. Our need to matter and our need to belong are as fundamental as our need to eat and drink. Ostracism—rejection, silence, exclusion—is one of the most powerful punishments that can be inflicted. Many of us left the church at that point, with a bitterness that came from feeling betrayed at our deepest core. When we needed kindness and understanding the most, our church utterly failed us.

There is some improvement in the atmosphere today, with dedicated parish ministries, people and clergy of good will who are warm and welcoming. Official church teaching now calls for tolerance and acceptance, but church practice frequently belies this. Countless stories continue to be recorded of lesbian and gay Catholics who are fired from parish or diocesan jobs simply for going public that they live in a same-sex relationship; couples who are booted out of pastoral ministries because they are married; and gay parents who have to constantly hear statements from church hierarchy that we are morally unfit to adopt or raise children. The church hierarchy continues to lead the charge that same-sex marriage will destroy the family, even civilization.

What is most laughable about this farce is that these statements are coming from mouths that have yet to publicly chastise and remove a brother bishop for protecting predator colleagues or priests at the expense of vulnerable children and young people. Gay men in the church have to deal with homophobia but Catholic lesbians have a double whammy: the issue of homosexuality, and the complete marginalization of ourselves as women.

In her testimony at a public hearing sponsored by the Boston Women’s Ordination Conference, in spring 1980, Dr. Lorna Hochstein addressed the topic, “Woman and Roman Catholic: Is it Possible?” What she said was:

“No: it’s not possible to be a woman and a Roman Catholic. And yet I am. Somehow I am. I am because I was born a Catholic, because I was raised a Catholic, because I think in Catholic categories and speak in Catholic vocabulary. I am a Catholic because I miss that church’s rituals when I’m without them, and because a cross hung with a body speaks infinitely more to me than one without the body. I am Catholic because my heart and soul want to be Catholic. I’m a Catholic one day at a time, one week at a time, and I’m a Catholic with varying degrees of intensity. Each time I go to a liturgy, I make a deliberate choice. Each time I say “Yes, I am a Catholic,” it is because on that day I can somehow believe that I am whole, valuable, and complete person who is also a woman; and on that day I am able to be such a woman in a church which denies me recognition of my full humanity by saying I am not able, that I am not adequate, to represent the humanity of Christ.”

“I am a human being, a female human being, before I am Catholic. I am a female human being called by God to minister to others as fully as I am able, and because of this, I live as a witness to the sinfulness of my church, the church that presumes to know what it is that God wants for me. More than that, it presumes to know what God wants and doesn’t want for every single Catholic woman in the world. Before I was born, my church knew that God would never call me or any other woman to be a priest, deacon or altar server. Before any woman is born, the hierarchy of my church knows that “God the Father” will be enough for each and every one of us. How can they presume so much?”

“Today I am a Catholic. Tonight as I speak, I am a Catholic. But I am a woman first, and as such, I live on the boundary of that institution, with one foot already outside. So I manage to keep my own self whole. I keep my sanity and live with this contradiction. Today I am a Catholic. But tomorrow I might leave.”

In the 41 years since those words were spoken one thing changed: we now have female altar servers in many parishes. An overwhelming majority of people who identify themselves as Catholic support women’s ordination. They also support same-sex marriage in a higher proportion than the U.S. population as a whole. Then why does the institutional church remain so resistant to even talking about change?”

Next: Finding Our Place as Catholic Lesbians: Chapter 3 – Courage

Kirkridge An unmet need for connection, support and affirmation was the spark behind the Conference for Catholic Lesbians (CCL) held at Kirkridge Retreat Center in November 1982. At that time, no Catholic women’s or gay organization spoke sensitively to the needs of Catholic lesbians, or in many cases, even acknowledged our existence at all. Except for a small presence in Dignity, we were invisible and voiceless.

The goal of the first conference was to come together with others who identified as Catholic and as lesbian; but also to articulate how these two identifications were often at odds in our church, in the gay and lesbian community, and in us. To be one, we had to hide the other. This lack of authenticity and wholeness affected every part of our lives and spirituality.

The conference organizers asked the participants what they hoped to get out of the conference. Among the major themes were the following:

-A greater understanding of myself as a Catholic lesbian; establish friendships with other lesbian women who treasure and nurture their spiritual selves; support and direction.

-A renewal of my Catholic faith and a way to combine it with my lesbianism to a workable balance.

-Prayer & community in a supportive environment. For three years I experienced those elements as a Sister of Mercy. Though it’s been five years since I left the community, the prayer, community and supportive atmosphere are still missed.

-Sharing ideas and experiences with other women of the same background and philosophy in an atmosphere of openness and acceptance. To be able to be proud of being a Catholic and a lesbian without punitive consequences.

-An answer to the question, “How can one be a sexually active lesbian and a Catholic?”

-Help toward resolving my indecision if a lesbian can be Christian, much less Catholic.

-To meet Catholic women, get a better view of women (gay) in the church and learn how to incorporate my Christian gayness in the straight world without becoming bitter.

-A sense of reassurance that Catholic lesbians have not abandoned the church; that God is an integral factor in other lesbians’ lives. An opportunity to discuss Catholicity with other lesbians.

-A greater appreciation of my place in the gay community as a deeply committed Christian woman.

-Meet new people, gain new insight, broaden my thinking and have fun.

-The opportunity to meet and talk with other Catholic lesbians. To share feelings/common problems. To be quite honest, just to be able to do something as a group of Catholic lesbians to come away with a feeling of belonging. That there really are more Catholic lesbians out there than the 1 or 2 we see at church occasionally.

Kirkridge vista What emerged from that weekend gathering was the realization that although there are many ways to identify as being Catholic or lesbian, we shared a bond to a faith with which we would always feel connected, even if we ceased to consider ourselves practicing church members.

What was special about Kirkridge and subsequent conferences was the opportunity to meet, hear and speak with other Catholic lesbians about shared gay experiences, especially the pain that often comes from a sense of rejection and exclusion. As one participated noted, “It is very rare to find lesbians who will own the fact that they have been/are part of the Catholic church. I hope to gain knowledge of other women’s experiences in order to share the past, and deal with the present with a new vision.”

Next: Chapter 2 – Anger and Sadness

Read the entire article here.The Importance of Being Who We Are3

I last saw Ed at the Christopher Street Festival in June 1988. Several dozen Conference for Catholic Lesbian marchers ended up at our booth in front of St. Veronica’s, we did a brisk business selling tee-shirts, buttons and handing out literature. It was a fun and exhilarating day. By connecting with the group and other Catholic lesbians, visitors were able to start to reconcile, or begin to come to terms with, the struggle of faith and sexuality. What they didn’t think was possible did exist.

Ed died of AIDS on February 28, 1989. His last job was at Trix, a gay hustler and strip bar in Times Square. A brief obituary appeared in section B, page 16 of the March 2, 1989, edition of The New York Times: “Edward Francis Murphy, a leader in the gay rights movement, died Sunday at St. Vincent’s Hospital in Manhattan. Mr. Murphy, who was 63 years old and lived in Manhattan, died of heart failure, said his longtime friend, Richard Mahoney. Mr. Murphy became a gay-rights advocate in the 1960s and founded the Christopher Street Festival, held annually the last week in June. He was the director of the One-to-One program at the Manhattan Development Center, a state institution for mentally retarded and developmentally disabled adults. Surviving are his mother, Dorothy, and a sister, Dorothy King, both of Queens. A memorial service is to be held today at 10 A.M. at St. Veronica’s Roman Catholic Church, 155 Christopher Street.” When Ed was arrested for his role in the “Chickens and Bulls” extortions he was living at 167 Christopher Street, close by St. Veronica’s.

St. Veronica’s Church, Christopher Street, NYC At Ed’s standing-room-only funeral, the priest remarked, “If Ed Murphy is not with God, then there is no God.” As pallbearers carried him to the hearse, a police escort stopped traffic and a tenor sang, “Danny Boy.” His obituary in the New York Native, a popular gay newspaper, described Murphy as “a patriarch to his own,” and said that “bigotry appalled him.” He was, the obituary stated, “a humanitarian with few peers whose like may not pass our way soon.” A few months later, Ed Murphy was named posthumous Grand Marshall of the 1989 New York City Gay Pride parade. The Cadillac Murphy traditionally rode in led the march, empty except for the driver.

I do remember that there was some opposition to him being named Grand Marshall. I didn’t know or can’t recall why some people didn’t want him honored—it was never stated clearly. I didn’t understand why people would object. It seemed to me that he did a lot for the gay community. Because he talked to me about it, I knew that Ed had a rough background between jail and jail violence. He spoke in a gruff, New Yawker way, but he was a good man and tried his best to help people. I appreciated what he did for us, and I was fond of him. At no time did I ever hear in conversation or read in gay papers about the Mafia involvement in Stonewall, or Ed’s past life as an extortionist and blackmailer.

In 1989, there were still lots of people around who knew Ed’s awful history. But not one word was written until author and journalist William McGowan’s ground-breaking article in the Wall Street Journal, “Before Stonewall” published on June 16, 2000; over a decade after Ed’s death. Why didn’t anyone come forward? Why was this information suppressed? Here’s one theory: people were afraid. If Ed was able to skate through the “Chickens and the Bulls” without going to jail—blackmailing rich, influential men—who was protecting him? What and who did he know that kept him walking around free? People who might have acted or spoken out chose discretion to save themselves a bad beating or worse. Whether this influence was true or not people believed that it was true and were afraid of him.

The silence regarding Ed Murphy is reminiscent of the silence surrounding the 1965 murder of Malcolm X. Decades later it came out the NYPD and FBI were involved in keeping track of Malcolm X using Black Muslim informants. Some members of the Nation of Islam also knew who the real killers were but didn’t say anything and let two innocent men be convicted and go to prison. Why? I believe that it was to protect themselves and their families from violence and to protect the reputation of the Nation of Islam. The reluctance that minority groups have toward exposing despicable deeds by their members is a defensive reaction to avoid more contempt and oppression by law enforcement and the public. It was better to forget than pursue justice. Like Ed Murphy, at least one of the killers hid in the open and volunteered for a lot of neighborhood charitable activities.

Ed Murphy had resentments and hostilities of his own, including a class resentment of affluent white men. “I resent the George Segal statue created in memory of Stonewall because those people in the statue don’t represent the people who fought back at Stonewall. Those are Fire Island guys in that statue. Those who fought were drag queens, Hispanics, street people.”

George Segal Statues, Greenwich Village, NYC Ed’s statement is true about the Stonewall Riots, but not about Gay Liberation. The latter was mostly the result of large numbers of middle class and affluent whites who came out, organized politically, and demanded change. White gay men, with their contacts and careers in business, law, media, arts, and the entertainment industry pushed hard, particularly with AIDS and later with marriage equality. Back in the late ‘70s, journalist Arthur Bell remarked on the discordant styles of Ed Murphy and the rising cohort of gay activists: “Then there’s his age, and his background, grating against the media image perpetuated by the Dewar’s White Label liberationists. It’s not right for the movement that the boss downtown looks as if he just stepped away from the crap game in Guys and Dolls. That Skull may embody gay liberation is difficult for them to perceive.” And his habit of referring to his “brothers” as “queens, cocksuckers, fags, and worse.”

Ed’s early class consciousness—like Trump era blue-collar resentment of elites—made it easier for him to shake down Wall Streeters and other professional men. He saw them use and discard prostitutes and return to their comfortable if closeted lives. Why not use them to make some money?

On the surface, it appears that after the Stonewall Riots, Ed Murphy experienced a metanoia like St. Paul on the road to Damascus. Before Stonewall, he victimized gay men as part of a money-making scheme; afterwards, he represented himself as one of few Stonewall habitues who really cared about gay rights. He continued to work in gay bars and clubs and expanded his large network of contacts and associates in the gay bar culture. He also became an active volunteer with mentally handicapped and disabled children and adults. By all accounts, he was very gentle and loving with them. Murphy also helped runaways, people with AIDSs and prostitutes who were broke and needed kindness and some cash. “When I was in jail,” he told a reporter, “a lot of people helped me. I’m trying to help somebody back.”

I asked my wife, Dr. Lori Mei, a social psychologist, how Murphy made such a complete change from brute to saint. “I don’t think that he necessarily did,” she said, “he just followed the money. He couldn’t continue to blackmail people; he was too identified at that point, but there was money to be found in charity and gay rights work.” Not as much money as in blackmail, but certainly enough to cobble a living between that and bar work. I think he also took pride in helping people out and was protective of people that he perceived as forgotten, scorned or unwanted.

Ed Murphy never expressed any regret for his role in the “Chickens and the Bulls” extortions or regret for the fear and misery suffered by his victims. Some saints led lives of depravity, but at some juncture expressed remorse for the evil they had done. “I ask Skull if he feels that he’s negating the bad in his life by doing good deeds,” said reporter Arthur Bell, “be it with the gay liberation movement, the crime commission, or the retarded.” “I don’t look at it that way,” Murphy answered. “My past is behind me. I was a crazy kid. I did crazy fucking things. I’m happy with what my life gave me.” Some people acknowledge their responsibility; some justify their misdeeds, others like Ed Murphy shrug them off and move on.

Ed Murphy, the Mafia at the Stonewall, and the “Chickens and the Bulls” scandal are pretty much forgotten today. That’s a shame. The shadowy interactions of these players shaped important episodes in gay, New York, and national history. What happened after Stonewall is the legacy of decades of mistreatment and contempt, and the need for homosexual men and women to lead a double life of quiet desperation. Men could satisfy their need for sex with prostitutes and one-night stands; many women had to be satisfied with close friends and fantasies. For centuries men caught with male prostitutes or decoys have been preyed upon by criminals. Since Ed Murphy procured and pimped, he was in a good position to blackmail.

The Stonewall Riots were a spontaneous public explosion by drag queens, teenagers and bar patrons who were fed up with being pushed around by police and exploited by mobsters. Gay Liberation started back in the 1950s with the Mattachine Society and the Daughters of Bilitis. It was propelled along by the same civil rights currents as the women’s liberation movement and Black Power but flexed a lot of muscle when middle class and affluent whites “came out” and were no longer subject to extortion. Ed Murphy the blackmailer and activist lit the fuse at Stonewall.

I met Ed Murphy almost 40 years ago. Ed reminded me of my father, a tough Irish city boy who made his own way. Ed was a hard man with a soft heart for people who shared his hardships. But I am also painfully aware of the men that Ed hurt, used, and ruined, especially the long-time Wall Street employees who lost their livelihoods and dignity because of Ed’s blackmail and thievery at Stonewall. “Stonewall” became a liberation icon to lesbians and gays around the world; but to the “old and trusted employees” who were turned out of their jobs on Wall Street because they were gay, and the blackmailed men searching for a way out of their loneliness, “Stonewall” was a source of misery and degradation.

Read the entire article. Ed_Murphy_Gay_Blackmailer_and_Activitist

Primary Sources for this Article

I am deeply indebted and grateful to the following writers for their research, books and articles on Ed Murphy, the Mafia, J. Edgar Hoover, and The Chickens and the Bulls scandal.

Phillip Crawford, Jr., The Mafia and the Gays; Queer Joints, Wise Guys and G-Men. A retired attorney, Crawford is a leading authority on the historic role of the Mafia in gay bars. From 2009 to ? Crawford blogged extensively about organized crime at “Friends of Ours.” The blog was located at http://bitterqueen.typepad.com. One particularly helpful post was “Stonewall Riots: A Gay Protest Against Mafia Bars – June 7, 2010. You can also find him online at https://phillipcrawfordjr.medium.com and his website.

Phillip Crawford William McGowan, Before Stonewall: Scandal, blackmail, a police crackdown. Shedding light on a forgotten case. The Wall Street Journal, June 16, 2000. The Chickens and the Bulls – The rise and incredible fall of a vicious extortion ring that preyed on prominent gay men in the 1960s. July 11, 2012. Mr. McGowan is a journalist. http://williammcgowan.com

Arthur Bell, “Skull Murphy – The Gay Double Agent. Village Voice, May 8, 1978. Arthur Bell (1939-1984) was a writer, journalist and gay rights activist who lived in New York City. Bell was a founder of the Gay Activists Alliance and wrote for many gay and mainstream papers, including the popular column, “Bell Tells” in the Village Voice.

David Carter, “Stonewall: The Riots that Sparked the Gay Revolution. St. Martin’s Press, 2004. David Carter gave a presentation before the United States Civil Service Commission on the History of the Stonewall Uprising and the LGBT Civil Rights Movement on June 7, 2019. His full statement can be read here – https://www.washingtonblade.com/2019/06/12/u-s-civil-rights-commission-reiterates-support-for-equality-act/

David Carter Douglas M. Childs, Ph.D., Professor of History at Penn State University. He has posted thousands of pages of FBI files on gays on his website: https://sites.psu.edu/dougsite/page-2/. He wrote a book, “Hoover’s War on Gays – Exposing the FBI’s ‘Sex Deviates’ Program, University Press of Kansas, 2015.

Anthony Summer, “Official and Confidential: The Secret Life of J. Edgar Hoover.” G. P. Putnam & Sons, 1993. https://www.anthonysummers.com. Summers specializes in investigative non-fiction books.

Karen A. Doherty and Barbara M., Conference for Catholic Lesbians (CCL) members and representatives, spoke and met with Ed Murphy around Gay Pride Day and the Christopher Street Festival – 1983-1988. https://nihilobstat.info/2006/06/10/edward-murphy-of-the-stonewall-inn/

Karen Doherty Additional Books, Newspaper Articles, & Blog Posts

Burton Hersh, Bobby and J. Edgar – The Historic Face-Off Between the Kennedys and J. Edgar Hoover That Transformed America, Carroll & Graf Publishers, 2007

Martin B. Duberman, Stonewall, Dutton, 1993

“Detective at Hotel is Held in Extortion,” The New York Times, August 5, 1965.

“Nine Seized Here in Extortion Ring – Hogan Says Gang Preyed on Homosexuals and Others,” by Jack Roth, The New York Times, February 18, 1966.

“Nationwide Ring Preying on Prominent Deviates – Bogus Policemen Victimize Theatrical Figures – Even Reach Into Pentagon,” by Jack Roth, The New York Times, March 3, 1966.

“3 Indicted Here as Sex Extorters – U.S. Charges Ex-Convicts Preyed on Homosexuals,” by Edward Ranzal, The New York Times, June 1, 1966.

William McGowan “Detective Accused as a Top Extorter,” The New York Times, July 1, 1966.

“Blackmail Paid by Congressman – Victim Among Thousands of Homosexuals Preyed by Ring of Extortionists,” by Jack Roth, The New York Times, May 17, 1967.

“Homo Nest Raided, Queen Bees are Stinging Mad,” by Jerry Lisker, New York Daily News, July 6, 1969.

“Christopher’s Emperor: Mike Umbers,” by Arthur Bell, Village Voice, July 22, 1971.

“Ex-Convict Brings Smiles to the Retarded” by Paul L. Montgomery, The New York Times, March 31, 1975.

“Edward Murphy, 63, A Gay-Rights Leader,” The New York Times, March 2, 1989.

SAGE (Senior Action in a Gay Environment) Newsletter, June 1989, New York, NY.

“Charges of Profit Skimming Roil ’92 Christopher Street Festival” by Peder Zane, The New York Times, June 26, 1992.

“J. Edgar’s Slip Was Showing,” by Murray Weiss, February 11, 1993.

Arthur Bell, 1970 “Partners for Life,” by Sidney Urquhart, Time Magazine, February 22, 1993. A review of the book, Official and Confidential: the Secret Life of J. Edgar Hoover by Anthony Summer.

“The Real Mob at Stonewall” by Lucian K. Truscott IV, The New York Times, June 26, 2006.

“Edward “The Skull” Murphy,” by R. Marc Kantrowitz, The Patriot Ledger, June 24, 2012.

“Half-Century Later, NYPD Apologies for Stonewall,” by Duncan Osborne, GayCityNews.com, June 6, 2019.

“Stonewall – Strange But True,” An Historian Goes to the Movies – Exploring history on the screen. Andrew E. Larsen, https://aelarsen.wordpress.com/2015/10/13/stonewall-strange-but-true/

“The Stonewall Inn,” A Gender Variance Who’s Who, Zagria Cowan, https://zagria.blogspot.com/2011/06/the-stonewall-inn.html#.YL6fyPlKhPZ

“Mafia Exploitation of Kids: Really a New Low?” Five Families of New York City. http://www.fivefamiliesnyc.com/2010/04/mafia-exploitation-of-kids-really-new.html

The website – Not Kansas – particularly “The Gay 60s, 1966-1970″

Douglas Childs

“Then Stephen took Angela into her arms and she kissed her full on the lips.” That sentence has thrilled tens of thousands of lesbian readers, including me, to finally see, feel, imagine their desire in print. When British novelist Radclyffe Hall (1880-1943) published The Well of Loneliness in 1928, it was the first widely read novel to feature lesbian love. A British court judged the book obscene because of the words “and that night they were not divided.”

It tells the story of Stephen Gordon, a woman given a man’s name by parents that wanted a boy, who is irresistibly drawn to other women. She was born on Christmas Eve and named after the first Christian martyr. As a girl she had a dream: “that in some queer way she was Jesus.” Seven-year-old Stephen develops a crush on the Gordon’s maid, Collins. When she discovers that Collins has “housemaid’s knee” she prays that the affliction be transferred to her. “I would like to wash Collins in my blood, Lord Jesus—I would very much like to be a Saviour to Collins—I love her, and I want to be hurt like You were.” Stephen is later devastated when she catches Collins sharing a kiss with the footman.

As a young woman Gordon has an affair when a neighbor’s wife. After a confrontation with her mother about her “unnatural” love, she retreats to her father’s study and discovers a book by German psychiatrist, Krafft-Ebing, on deviant sexuality. After she reads it, she understands what she is—a female “invert,” a lesbian. She opens a Bible, and seeking a sign, reads Genesis 4:15: “And the Lord set a mark upon Cain…” Radclyffe Hall used the mark of Cain, a sign of crime and exile, throughout the book for the status of “inverts.”

Stephen meets Mary Llewellyn, the love of her life, in France during World War I. The two set out to build a life together, but Stephen believes that Mary’s life is suffering because as a couple they are an object of scorn and contempt. To “save” her, she feigns an affair with another woman to drive Mary into the arms of a man who admires and wants her. Mary leaves her and marries. Stephen is devastated and alone. She has a vision of being thronged by millions of inverts from throughout time, living, dead and unborn. They beg her to speak with God for them. Possessing her, she articulates their collective prayer: “God,” she grasped. “We believe, we have told You we believe…We have not denied You, then rise up and defend us. Acknowledge us, oh God, before the whole world. Give us also the right to our existence!”

Radclyffe Hall was a pioneer in her efforts to reconcile Christianity and homosexuality. Her defense of gay men and lesbians took the form of a religious argument: if God created inverts, the rest of humanity should accept them. Declaring homosexuality to be a “part of nature, in harmony with it, rather than against it.” She posed the question to her attackers: “if it occurs in and is a part of nature, how can it be unnatural?” She also knew the price that gay and lesbian people pay to remain in the closet and railed against the “conspiracy of silence” saying, “Nothing is so spiritually degrading or so undermining of one’s morale as living a lie.”

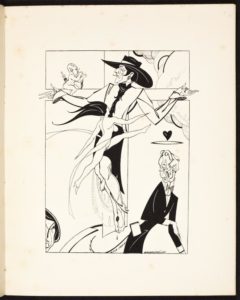

The controversy over The Well of Loneliness was lampooned in The Sink of Solitude, a satirical pamphlet by Beresford Egan, novelist, and illustrator. One drawing shows an immediately recognizable Radclyffe Hall with her trademark Spanish riding hat nailed to a cross. A near-nude Sappho leaps in front of the martyred “St. Stephen” and Cupid perches on the crossbeam. While Egan agreed with Hall’s arguments, he spoofed her piety and moralizing.

Radclyffe Hall is like many Catholic lesbians I have met: conventional, judgmental, spiritual, and often promiscuous.

She was born Marguerite Radclyffe on August 12, 1880 at Christchurch, Bournemouth, England. In later life she was called John by her friends and lovers, and M. Radclyffe Hall or Radclyffe Hall in her books. Her mother, Marie, was an American and her father, Radclyffe Radclyffe Hall, was English. Her parents divorced when she was two and Marie remarried a musician, Albert Visetti. The young girl never liked him. She reached young womanhood without much education or interests except chasing women. Her specialty seems to be the seduction of married women.

In 1907, at 27, unattached and drifting, Hall made a trip to Bad Homburg, Germany, known for its wellness spas and baths. She became smitten with Mabel (Ladye) Batten, a renowned beauty and amateur singer. Batten’s portraits were painted by John Singer Sargent and Edward John Poynter. The 50-year-old married grandmother had ties to aristocratic society and was rumored to have had an affair with King Edward VII. The poet-adventurer Wilfrid Scawen Blunt was an admirer. Witty, elegant, cultured, beautiful and worldly, Batten was everything Hall desired. They became lovers and stayed together until Batten’s death in 1915.

Batten was a major influence on Hall, and encouraged her to write poetry. Hall’s first book of poems, A Sheaf of Verses, published in 1908, reveals her first, tentative references to homosexuality. A second book of poetry including the “Ode to Sapho” was published later that year. Her third volume came out a year later. When Batten’s husband died in 1910, the two women made a home together. Hall’s fourth poetry anthology was dedicated to Batten.

Batten was politically conservative, and Hall adopted her positions. Ladye was also a Catholic convert, and under her encouragement and influence, Radclyffe Hall was received into the Catholic church on February 5, 1912. She was 32. Her baptismal name was Antonia, and she chose Anthony as her patron saint. Hall and Batten worshiped together at London’s fashionable Church of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, known as the Brompton Oratory. In 1913, Hall and Batten made a pilgrimage to the Vatican. They went to Mass at St. Peter’s Basilica. Pope Pius X blessed them in a semi-private audience with other substantial donors. They returned to London with religious-themed triptychs, gilt angels and an alabaster Madonna.

The refined Ladye was both a maternal and wifely figure for Radclyffe Hall. The once-feminine Hall, who wore skirts all her life and only had her waist length blond hair cut in her 30s, started to cultivate a more masculine appearance, close-cropped hair, tailored jackets and bow-ties. Batten gave Hall the nickname “John” after noting her resemblance to one of Hall’s male ancestors. She used this name for the rest of her life. Was Hall butchy, a butch, stone butch, or these days – a transman? It’s hard to say. She said that she had a man’s soul in her body.

In 1915, 35-year-old Radclyffe Hall met Una Troubridge (1887-1963), a 28-year-old cousin of Mabel Batten, at a tea party in London. They were immediately sexually attracted to one another and began an affair. Their relationship that would last until Hall’s death in 1943. Troubridge was a sculptor and mother of a young daughter. She was married to Vice-Admiral Ernest Troubridge, a career naval officer who was 25 years her senior. Hall’s affair with Troubridge caused an uneasy situation among the three women.

In May 1916, Batten suffered a cerebral hemorrhage after a quarrel with Hall over Troubridge. She died ten days later. Guilty and grief-stricken, Hall believed her infidelity had hastened Batten’s end. She had Batten’s body embalmed and buried her with a silver crucifix blessed by Pope Pius X. Soon after Batten’s death, Hall and Troubridge developed an interest in spiritualism and began attending seances with a medium, Mrs. Gladys Osborne Leonard. They believed Batten’s spirit gave them advice.

Most of the stories, poems and novels Radclyffe Hall wrote touched on Christian themes, Catholic imagery, lesbian desire or all three. In 1924, Radclyffe published The Forge, a fictionalized portrait of American lesbian artist Romaine Brooks, and The Unlit Lamp, a novel about a girl who dreams of going to college and setting up a “Boston marriage” with her tutor, Elizabeth. A Saturday Life (1925) follows the life of a girl who takes up and discards many artistic pursuits with the support of an older woman who is in love with the girl’s mother. Hall’s fourth novel, Adam’s Breed (1926) centered on the spiritual struggles of a young man over excess consumption by modern society. He becomes disgusted with his job as a waiter and even with food itself, gives away his belongings and lives as a hermit in the forest. The story also reflect’s Hall’s concern about the plight of animals. The book won the 1926 James Tait Black Memorial Prize for fiction and the Femina Vie Heureuse Prize for best English novel.

In early July 1926 Hall completed the short story, “Miss Ogilvy Finds Herself,” which dealt with homosexuality. Later than month she began writing Stephen, the novel that became The Well of Loneliness (1928). The Master of the House (1932) is an adaptation of the Christ story in a contemporary setting. Christophe Benedict, the main character, is a deeply spiritual and compassionate carpenter who lives in Provence, France. He is born to a carpenter named Jouse and his wife, Marie. Christophe ends up being crucified by Turks in Palestine during World War I. Writing the book was so spiritually intense that Hall developed stigmata on the palms of her hands.

In the 1930s Hall and Troubridge made their home in Rye, a village in East Sussex where many writers lived. Hall used Rye as the setting for the book, The Sixth Beatitude (1936), her last novel. It is the story of Hannah Bullen, a strong-bodied young woman. Hannah Bullen’s unconventional life (unmarried mother of two children) is beset by poverty and strife within her family. Hall uses the sixth Beatitude to portray Bullen’s purity of heart and mind by sticking with them. An independently wealthy heiress, Hall gave generously to the local church. Saint Anthony of Padua was constructing a new building when they moved to Rye. Biographer Diana Souhami wrote that Hall “poured money into the church” to bring it to completion and furnish it. “She paid for its roof, pews, outstanding debts, paintings of the Stations of the Cross and a rood screen of Christ the King. A tribute to Ladye was engraved on a brass plaque set into the floor: “Of your charity, Pray for the soul of Mabel Veronica Batten, In memory of whom this rood was given.”

What is the attraction of lesbian and gay men to Catholicism? Why did so many late 19th century writers, intellectuals, artists, clergy and bohemians (with gay lovers, tendencies or friends) take the plunge into the faith? Notable converts include Oscar Wilde, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Aubrey Beardsley, lovers Katherine Bradley and Edith Cooper, Ronald Firbank, Maurice Baring, Eric Gill, Robert Hugh Benson, John Henry Newman, Frederick Rolfe, Marc-Andre Raffalovich, John Gray; and, of course, Mabel Batten, Radclyffe Hall and Una Troubridge.

Oscar Wilde opined on the attraction of the Roman Catholic Church for outre artistic figures and rebels. He said that Catholicism was “for saints and sinners,” while…” for respectable people, the Anglican Church will do.” Becoming Catholic was an act that allowed one to become both rebellious and steeped in tradition. Irish playwright and novelist Emma Donoghue observed: “Being Catholic in England meant becoming slightly foreign, aloof from the establishment; as a church it was associated with the rich and the poor, but definitely not the bourgeoisie.” For much of English society, to become Catholic was to cross society’s lines to a suspect, “other,” even deviant, religion. But the “otherness” may have been a reason behind its attractiveness.

The sensuousness and eroticism present in Catholic art and ritual have a magnetic appeal to lesbian and gay people. Beautiful men, barely covered; women with their heads thrown back in orgasmic passion—a feast for the eyes and imagination. We can appreciate symbolic and hidden meanings, the emphasis on the body, particularly the Eucharist, where we take the body of Christ into our mouth; and the mystery inherent in ourselves and in the spiritual world.

Modern scholars have explored the role of religion in Radclyffe Hall’s work. Catholic Figures, Queer Narratives (2007) includes the chapter “The Well of Loneliness and the Catholic Rhetoric of Sexual Dissidence” by Richard Dellamora. He explores Hall’s life and work. Ed Madden, English professor at the University of South Carolina, examines Hall’s use of Christ’s imagery and symbolism in Reclaiming the Sacred: The Bible in Gay and Lesbian Culture (2003) edited by Raymond-Jean Frontain.

Like a bee sipping nectar from flower to flower, Hall’s desire for women never waned. Her indiscretions as “man of the house” could be overlooked as long as they were brief. Una Troubridge and Radclyffe Hall stayed together as a couple until Hall’s death in London from colon cancer in 1943. The relationship survived Hall’s numerous flirtations and Hall’s last torrid affair with her 28-year-old White Russian nurse, Evguenia Souline (1906?-1958). Souline was hired to help care for Hall during an illness, and their relationship blossomed into much more. Despite the initial protests of Troubridge, the three women lived together in Florence, Italy. At the outbreak of World War II they left and settled in Devon, England. “Darling—I wonder if you realize how much I am counting on your coming to England,” Hall wrote to Souline, “how much it means to me—it means all the world, and indeed my body shall be all, all yours, as yours will be all, all mine, beloved. And we two will lie close in each others arms, close, close, always trying to lie even closer, and I will kiss your mouth and your eyes and your breasts—I will kiss your body all over—And you shall kiss me back again many times as you kissed me when we were in Paris. And nothing will matter but just we two, we two longing loves at last come together. I wake up in the night & think of these things & then I can’t sleep for my longing, Soulina.” Una Troubridge cannot have been happy reading that note. Even so, much of Hall’s correspondence to Evgenia Souline has been preserved. Troubridge burned Souline’s letters to Hall.

Radclyffe Hall died at her flat in Pimlico on October 7, 1943. She bequeathed her entire estate to Troubridge. At her request, she was buried in a vault next to Mabel Batten in Highgate Cemetery in London. Souline was given a small allowance and disappears from the story. At the time of her death, The Well of Loneliness had been translated into 14 languages and was selling more than 100,000 copies a year. It has never gone out of print. For decades, it was the only lesbian book generally available.

Troubridge, now a wealthy woman, moved to Italy and died of cancer in Rome in September 1963, at age 76. Shortly before Troubridge died, a woman asked her how she and Hall reconciled their relationship with their Catholic faith. What did they do about confession? Troubridge answered, “There was nothing to confess.” Troubridge left written instructions that her coffin be placed in the vault in Highgate Cemetery where Hall and Batten had been buried, but the instructions were discovered too late. She was buried in the English Cemetery in Rome, and on her coffin was inscribed, “Una Vincenzo Troubridge, the friend of Radclyffe Hall.” Years later her tomb was removed and her remains were lost.

The Well of Loneliness has been criticized by lesbians for its stereotypical butch-femme coupling, energetic lesbians who are always masculine looking, and requisite unhappy ending of a love affair or relationship between two women. What is totally ignored is Hall’s Christianity and Catholic faith in her life and writing. A friend once observed to me that it is easier to be a lesbian in the Catholic Church than a Catholic in the lesbian community. Like 19th and 20th century biographers who often left out, or slyly alluded to their subject’s homosexual life; too many “herstory” archivists, writers and editors deliberately omit lesbian religious faith and commitment. This bigotry needs to stop.

“Who are you to deny our right to love” – Radclyffe Hall The Well of Loneliness

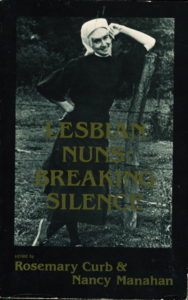

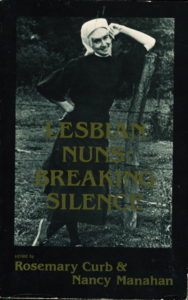

In 1985 the book, Lesbian Nuns: Breaking Silence, was published by Naiad Press. It was an explosive best-seller, thanks to the Boston Archdiocese and Cardinal Bernard Law, who complained about a local television interview with the book’s two editors. The archdiocese described the program as “an affront to the sensitivity of Roman Catholics.” The station cancelled the segment, and sales soared. “This is crazy,” Barbara Grier, a founder of Naiad Press told The New York Times, scrambling to fill orders for the book, “I’m a mouse giving birth to an elephant.” The editors, Rosemary Curb and Nancy Manahan, did have a successful appearance on the Phil Donohue show in April 1985 and went on a national tour for the book. Naiad Press went through four printings of the book, and eventually sold the mass distribution and paperback rights to Warner Books in 1986. Lesbian Nuns eventually sold several hundred thousand copies.

Lesbian Nuns: Breaking Silence included stories by 42 former nuns and women religious, and nine women still in religious life. Most used pseudonyms. All of them wrote about either discovering or acting on their lesbian identity while still in religious life. While there were very few detailed descriptions of sex and seduction, Naiad’s marketing promised to reveal what really goes on behind convent doors, breaking the silence “about erotic love between women in religious life.” While the lesbian religious in the book had affairs or relationships with other sisters, they also fell in love or lust with lay women, married and single. Often the love affair or sexual relationship was the cause of them leaving the convent: it was too hard to maintain a lover relationship and live a religious life. Sometimes the relationships continued but often they did not. I met and knew several of the contributors:

Nancy Manahan, one of the co-editors, worked with the Conference for Catholic Lesbians (CCL) to solicit contributors to the book. She also did a workshop on the book at our 1986 conference. I found Nancy to be a lovely, gracious, caring person.

Susan Weaver was an elegant, elderly woman. We got together several times during my visits to my parents home in Vermont. She made me a beautiful Christmas ornament that I put on my tree every year in memory of her.

Pat O’Donnell was a Dominican sister working at Picture Rocks Retreat house in Tucson, Arizona. She lost her job as the result of her coming out in the book. Pat continued to live and work in Tucson doing spiritual direction.

“Kate Quigley” lived in Montreal and had a long-term relationship with a married woman. The woman’s husband was aware of it. The three of them would go away on vacation together.

Charlotte Doclar worked with Sr. Jeannine Gramick at New Ways Ministry to outreach to lesbian nuns. I met her at a retreat for Catholic lesbians in 1981. Charlotte was friendly, jocular and good-natured. Her story is on the LGBTQ Religious Archives Network.

Dianne Weyers entered her community when she was 14. She left when she was in her late 30s or early 40s with a mysterious back ailment no doctor was able to diagnose but had a crippling effect on her. Since she could not sit upright for long, I typed her manuscript for the book. She felt very unwanted and persecuted by her community, particularly one sadistic superior. I never quite knew what to make of her.

“Sister Maria Nuscera” was a very vivacious lesbian religious in the Midwest. She fell in love and had an affair with a parishioner.

Margaret “Peg” Cruikshank was not one of the lesbian nuns but was one of the driving forces behind the creation of the book. Rosemary Curb and Nancy Manahan, the book’s co-editors, had previously published their own stories as lesbian religious in The Lesbian Path. Peg edited that book and introduced the pair in June 1981. She suggested to Barbara Grier that Manahan and Curb edit a book about lesbian nuns.

The nun on the cover of the book with the “come hither” look was Jean O’Leary, who left the convent and went on to become a co-director of the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force.