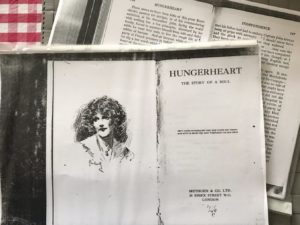

The First Catholic Lesbian Book: Hungerheart -The Story of a Soul

Hungerheart is a lesbian novel written by British author Christabel Marshall under her adopted male name, Christopher St. John. The book was published in 1915 in London by Methuen & Co. The novel is a first-person account of Joanna, “John” Montolivet that follows her search for love and passion. At one point she lives with Sally, a young actress, and they are “happy as a newly married pair, perhaps happier…” Sally decides to marry a man, and Joanna/John finds solace in the arms and bodies of stormy and dramatic women. Eventually she heads for quieter shores, and coverts to Catholicism. Her “friendship” with a young nun fulfills her heart’s hunger. “There are things that can be lived, but not chronicled, and our friendship is one of them,” Joanna/John describes. “Who in the world could understand our moments of union? Who in the cloister either? But they are understood in heaven…Thy love for me is wonderful, passing the love of men.”

Hungerheart never achieved the fame of another book written a decade later by another Catholic lesbian—Radclyffe Hall’s, The Well of Loneliness. Only a few copies of Hungerheart survive in research libraries. For some odd reason, it was not tagged with a homosexual or degenerate label but cataloged as a work about “Catholic spirituality.”

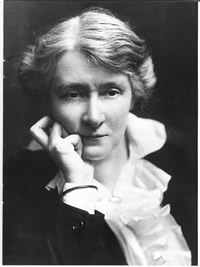

The author’s book embodied her voracious love life. Christine Gertrude Marshall a.k.a. Christopher Marie St. John (1871-1960) was an English suffragette, a playwright and writer. After college, Marshall served as secretary to Lady Randolph Churchill and actress Dame Ellen Terry. Marshall became romantically involved with Dame Ellen’s daughter, Edith (Edy) Craig (1869-1947). The two women began living together in 1899. Marshall attempted suicide when Craig accepted a marriage proposal from composer Martin Shaw in 1903. Edith Craig was an actress, director, producer and costume designer.

In 1912 Christabel Marshall converted to Catholicism and took the name, St. John out of affinity with St. John the Baptist. Her friend, Claire Atwood, converted around the same time. Atwood gave Una Troubridge and Radclyffe Hall, another Catholic couple and close friends, a relic of the true cross acquired by her ancestors from a pope. Una put it with candles and flowers in a shrine in her bedroom.

In 1916, artist Claire (Tony) Atwood (1866-1962) moved in with Craig and Marshall. Their menage a trois lasted until Craig’s death in 1947. Una Troubridge used to call them, “Edy and the boys.” They often wore men’s attire to match their male names. “Miss Craig,” wrote Virginia Woolf in her diary, “is a rosy, ruddy ‘personage’ in white waistcoat, with black bow & gold chain loosely knotted.” Marshall wrote rhat the three women “achieved independence within their intimate relationships…working respectively in theatre, art, and literature, and drew creative inspiration and support from one another.”

In 1932, when she was sixty-one, Marshall fell madly in love with Vita Sackville-West, a member of the Bloomsbury Group and a successful poet and writer. Their affair continued for several years and caused huge fights between Marshall and Craig. Atwood unsuccessfully tried to serve as a peacemaker.

In 1935, under her male name, Christopher St. John, Marshall wrote a biography of a distinguished physician, Dr. Christine Murrell, the first female member of the British Medical Association’s Central Council. Titled, “Christine Murrell, M.D., Her Life and Work,” St. John/Marshall wrote the dedication to both of Murrell’s lovers: Honor Bone, M. D. and Marie Lawson, a printer, editor, and tax resister. Like St. John/Marshall, Murrell had a threesome household.

Christabel Marshall/Christopher St. John died in 1960. She is buried next to Claire Atwood at St. John the Baptist’s Church, Small Hythe, England. This is the church where Dame Ellen Terry worshipped and where her funeral Mass was held in 1928. Edith Craig’s ashes were supposed to be buried there as well, but by the time of Marshall’s and Atwood’s deaths, they had been lost. A memorial was placed in the cemetery instead.

Why did so many Anglican clerics, creatives and/or socially prominent gays and lesbians convert to Catholicism in the Victorian and Edwardian eras? The Catholic Church has always been opposed to homosexual sex; but it also has been tolerant of gay sex among its members, including priests, the hierarchy and religious, as long as they were discreet and parroted official teaching in public. At that time, being Catholic was a little naughty, not socially acceptable, and showed a streak of rebellion and independence. Creatives were drawn to the sensuousness, the pageantry, and the mysteries in Catholicism. Catholicism emphasizes the body—the body of Christ in our mouth, the bodies of saints who give themselves up to pain and ecstasy, the homoerotic images found everywhere there are Catholic artists and cathedrals. For women, Catholicism offers many role models of women who lived full and fulfilling lives—without men.