|

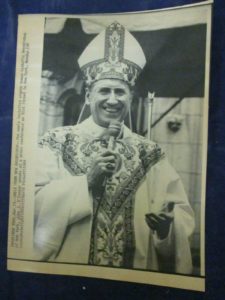

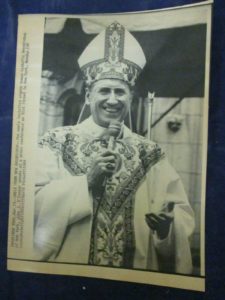

Cardinal Krol (left) Pope John Paul II celebrating Mass Cardinal John Krol, archbishop of Philadelphia (1961-1988), tried to dissuade Kirkridge, a Christian retreat house in Bangor, Pennsylvania, from hosting the first Conference for Catholic Lesbians in November 1982. Nothing public, just behind-the-scenes pressure. The caller first asked, then threatened. The Cardinal’s office didn’t have any leverage, since Kirkridge Retreat Center is an interfaith Christian community, not a Roman Catholic institution or organization. The Kirkridge staff had backbone, the request came to naught. Cardinal Krol did not want any public Catholic lesbian gathering in the neighboring diocese (Allentown) which was part of his ecclesiastical province. It would be a scandal.

I know this, because I received a call from my contact at Kirkridge to let me know that this had happened, and to reassure me we that we could still host our event there.

Who tipped Cardinal Krol’s office off, I don’t know, because at that time, we had barely begun to circulate notice of the conference. They must have seen an invitation letter to a speaker, picked up gossip from Dignity, or heard a rumor via a gay clerical network.

Cardinal Krol was described by New York Times writer Peter Steinfels as “an outspoken defender of traditional theology, hierarchical authority and strict church discipline.” He was also one of the first Catholic prelates to align with Republic Party figures. A photo taken in 1981 shows him with President Ronald Reagan.

Krol was used to working behind the scenes to stop scandals. In 2003, the report from a Philadelphia Grand Jury strafed Cardinal Krol and his successor, Cardinal Anthony Bevilacqua, charging that they protected predator priests and concealed sexual abuse of boys and girls. On page 30 of the report it notes: “For most of Cardinal Krol’s tenure, concealment mainly entailed persuading victims’ parents not to report the priests’ crimes to police, and transferring priests to other parishes if parents demanded it or if “general scandal” seemed imminent.”

The Conference for Catholic Lesbians (CCL) had a second conference at Kirkridge in 1984. There was no warning call from the Philadelphia Chancery this time. My feeling is that Cardinal Krol had bigger fish to fry that year including preparing the opening invocation at the August 1984 Republican National Convention. In his remarks, Krol agreed with comments that President Reagan had made earlier in the day that religion and politics are inseparable. “Our Republic was conceived and survived only on moral and religious foundations,” Krol said. “The most important right of all,” Kroll emphasized, “is the right of life, which must be protected by the government.”

Protecting the unborn was a high priority for Cardinal Krol. Protecting the institutional Church from scandal was also very important to him–more important than the life and faith of abused children and their families. How else could he justify reassigning priests who sexually violated children and teens to a new parish to continue the cycle of abuse?

Archbishop O’Connor, 1984 John J. O’Connor, Bishop of Scranton, Pennsylvania, arrived in New York City in January 1984. He was named Archbishop of New York shortly before his installation and made a cardinal by Pope John Paul II in 1985. O’Connor stayed in the news, and in the center of multiple controversies until he died in 2000. He was very passionate about several issues, particularly opposition to abortion and support of organized labor. He also didn’t mince words about lesbian and gay people: no hiring, housing, or civil rights protections. From the start he was a relentless foe of Mayor Edward Koch’s Executive Order 50, a directive which prohibited “agencies that receive city funds from discriminating against homosexuals in employment.”

Although he denied it, O’Connor pressured Francis Mugavero, Bishop of Brooklyn, to shift his diocese’s stance of engagement with gay people to stiff opposition to legal protections. In February 1984 they issued a joint statement in which they claimed that the gay rights bill was “exceedingly dangerous to our society,” explaining, “We believe it is clear that what the bill primarily and ultimately seeks to achieve is the legal approval of homosexual conduct and activity, something that the Catholic Church, and indeed other religious faiths, consider to be morally wrong. Our concern in this regard is heightened by the realization that it is a common perception of the public that whatever is declared legal, by that very fact, becomes morally right.”

Archbishop O’Connor was very clear on his position about homosexuals in the church’s employ–“We have said repeatedly that we have no problem whatsoever in employing people admitting to or not admitting to homosexual inclinations. If an individual avows engagement in homosexual activity, then we want to be able to say whether or not we will employ that person in this particular job, and we feel this is a perfectly appropriate thing for any agency. You know, we have five thousand, seven hundred youngsters in child-care agencies, and they are the ones currently at issue.” O’Connor said it would be wholly alien to Catholic teaching to employ in a child-care agency someone who openly advocated homosexuality.

In September 1984, I was a member of a delegation from the Coalition for Lesbian and Gay Rights (CLGR) who met with Archbishop O’Connor at the New York Catholic Center to discuss Executive Order 50. Terrence Cardinal Cooke, O’Connor’s predecessor, had refused to meet with Dignity/New York to discuss it. Coalition representatives were packed with Catholics, some of whom were members of Dignity and the Conference for Catholic Lesbians (CCL). When we arrived at the building, all in business attire, the guard at the door waved us through saying, “This way, ladies, or whatever…” As we got on the elevator, someone who knew who we were and where we were headed whispered, “Good luck.”

We were ushered into a conference room to wait for Archbishop O’Connor. I had a seat toward the end of the table facing the door. I saw Archbishop O’Connor striding down the corridor towards the meeting room. He was alone; no aides accompanied him. He looked grim. I don’t know what possessed me, but I winked at him. He winked back! We smiled. O’Connor walked into the room and walked around the table shaking everyone’s hand. I thought, “Perhaps there’s hope.” He sat down and the meeting started.

I can’t remember what was said, but all our arguments and personal experiences of ridicule, threats, and rejections by our friends, family, co-workers and faith based on our sexual orientation didn’t affect him. He said something to the effect that the Church would never accept us in the way we wished to live. The table went totally silent. It was a stunning moment; I felt the pain from his statement totally wash over me. I cried. Several other people at the table also cried, including a man who had recently lost his children in a custody battle. I turned to look at Archbishop O’Connor and saw that he looked surprised. He may have thought that our firmness and anger at our Church meant that we hated it or didn’t care. The opposite was true. There was nothing else to say and we left.

A few weeks later, I decided to write him a thank you note for the meeting. I told him I appreciated that he met with us and listened to what we had to say. I also said that while we strongly disagreed, I had respect for him for his straightforward expression of what he believed.

Three weeks later I received a reply to my letter.

Dear Karen:

Your letter…was extraordinarily kind and touched me deeply. I am indeed grateful. It is my sincere hope and prayer that through the years ahead I will be able to serve you in some way that you will consider helpful. My convictions about Church teaching are very deep. I do not anticipate a change in such teachings, and neither do I see it precluding our loving one another as brothers and sisters in Christ.

Please believe that I will give deeply sincere consideration to any recommendations that can help us in that regard in accordance with the tenets of the church which I am certain we both love.

You and your associates are very much in my masses and my prayers, and I ask that you keep me in yours as well.

Faithfully in Christ,

John J. O’Connor

We never spoke, or saw one another again, but the experience of meeting Archbishop O’Connor helped to guide me on how to engage with others with whom I don’t agree:

-Listen to adversaries as well as friends. One discussion may not change any minds, but it will have an impact and it shows a basic respect and courtesy.

-Look for the good in people. See a whole person, not just an opinion or point of view.

-Persevere. The Coalition members at the O’Connor meeting continued the fight for gay and lesbian civil rights. Dignity and CCL continued to work for the respect and recognition of lesbian and gay people in the Church.

On March 20, 1986, the New York City Council passed a homosexual rights bill by an unexpectedly wide margin of 21 to 14. The bill forbade discrimination based on sexual orientation in housing, employment, and public accommodations. The bill did provide an exemption for religious institutions.

The fear that the Archdiocese of New York expressed came true: public protections guaranteed by law did change public perception of lesbian and gay people. The widening acceptance and protection encouraged people to live and love more openly. As more and more gay people came out to their friends, family and colleagues, media portrayals also changed, which encouraged even more people, and younger people, to come out.

In 2013, even the highest level of the Church changed. In response to a question from the news media about a gay priest, Pope Francis made the statement, “Who am I to judge?”

Image by Federica Bordoni I went through the entire history of the Conference for Catholic Lesbians (1982-1996) in preparation for this article. In the many letters, notes, articles and comments I read, all the women, regardless of where they were on the spectrum of being Catholic and lesbian, said the same thing: it is very important for me to be who I am. I need to discover all of who I am and would like to do this within a community where I feel safe and understood. I want to be with others where I will feel supported and affirmed in my spiritual and sexual identity. And most of all, I would like to be heard and respected as I talk or pray from the reality of my life.

Susanne S. wrote an op-ed piece for her local paper called, “At Peace with Faith, Sexuality,” For those of us who identify as Catholic and lesbian, it elegantly, and very simply and clearly articulates how we have reconciled what appears on the surface to be a contradiction in terms.

“When I was growing up,” she writes, “I had two passions: one was God, the second was women. Though I have gone through a lot of soul searching with both, neither of those things has changed. I always felt a deep reverence and comfort in the church, and most specifically the Catholic Church. Two years ago, I converted to the Catholic faith, something I had wanted to do all my life. Fortunately, I found a wonderful parish to do this in.

Two years ago, in June, I rediscovered my true sexuality. My sexuality has been a little less easily professed than my faith in God, since, of course, there are so many attitudes that work to repress it. However, through this blessing, I realize life is not worth living unless I can include this part of myself, no more than it is worth living if I cannot profess my faith. All the wonderful feelings I had left behind, along with my ability to write poems, came back to me. I felt whole again. Even without a significant relationship on the horizon, my life has continued to become so much brighter.

To many people my being so intensely Catholic and lesbian at the same time may seem hypocritical. After all, doesn’t the Catholic Church condemn lesbianism and homosexuality in general? And to many feminists and lesbians, Catholicism represents the height of the patriarchy. Yet for me there is no conflict of interest. I recognize the church as an imperfect, human interpretation of Christ’s perfect teachings. I do not believe every word in the Bible is true, or that our pope speaks for God. What I do believe is that God in His/Her infinite wisdom and compassion can bring forth inspiration in spite of prejudice.

The Catholic faith speaks to me, not because it is accurate in hierarchy or rule, but because it feels accurate to me in feeling and in spirit. I also know, unlike many women who are not lesbian and fear the idea of lesbianism, that love as a lesbian is as Godly as heterosexual love is. My feelings are an experience of joy that matches the joy I feel when I watch a priest consecrate the host or present us with a newly baptized child.

I am sorry that there is so much fear and cynicism in the world that some straight people look at my lesbianism as sad and misguided (or worse), and some lesbians look at my love for the Catholic Church as naïve or anti-woman. I hope one day there will be more people who can see the ability to marry their faith with their sexuality. I thank God for both of those parts of me.”

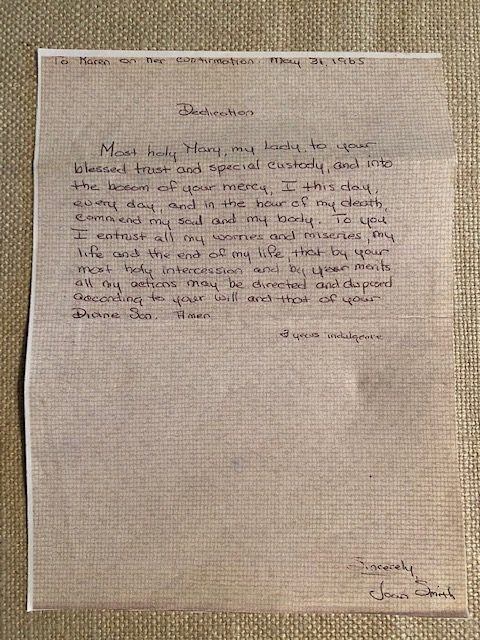

Joan Smith’s gift note Where does Faith begin? Mine began with a gift. May is typically the month for confirmations, and every May at Pentecost I remember my own, at St. Paul’s in Princeton, NJ. As we were getting ready for church, my sponsor came to the house. Unexpectedly, she brought another woman with her—a woman she introduced as her roommate. I hope I was friendly when we met, I was nervous and numb, and afraid Bishop Ahr would ask me a question I couldn’t answer. Too many times I went outside to play baseball or shoot hoops instead of sitting in the kitchen memorizing my confirmation questions.

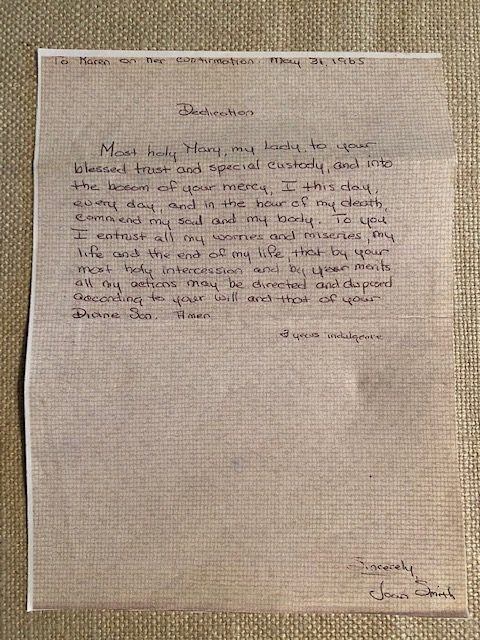

My sponsor’s friend was named Joan. She said she wanted to come and meet me. She had heard a lot about me from my sponsor, and she wanted to give me a gift on the occasion of my confirmation. It was her own statue of the Blessed Mother, given to her many years before. The note that accompanied her gift read:

To Karen on her confirmation, May 31, 1965

Most Holy Mary, my Lady, to your blessed trust and special custody, and into the bosom of your mercy, I this day, every day, and in the hour of my death, commend my soul and my body. To you I entrust all my worries and miseries, my life and the end of my life, that by your most holy intercession and by your merits all my actions may be directed and disposed according to your will and that of your Divine Son. Amen

The bottom of the note was signed, “Sincerely, Joan S-“

I never saw her again, or heard from her, or heard of her. I did not know who she was, or what her relationship was to my sponsor, although I suspect I do now. My sponsor, parents and I went off to St. Paul’s for the ceremony. At the altar rail, my sponsor gave my shoulder a reassuring squeeze as the bishop approached. I stopped being nervous. Like a ghostly visitation that replays itself every May anniversary, I see a tall woman with short brown hair smile warmly at a shy and nervous 12-year-old in a white robe and red cap. She entrusts her with a precious gift, one she hopes will protect and comfort her always.

How is Faith lost? When trust is lost. In an article that I wrote for CCL’s newsletter, “Images,” I asked: “what can we do if we are not reaching you?” I was touched by several of the responses I received. One letter began:

“When you wrote, “If we are not reaching you . . .the memories of the great bond, the exhilarating feeling of the fall [conference] of ’88, all make me want to reach out to you and the women who helped make it possible with an embrace. ‘Cause you all filled a great void in me at that time. But I have a personal problem to deal with now. To a question of faith, the need for it, the lack of it, the search for it. My faith has been going down steadily for a long time now, until I can come to the point of saying: I am not a Catholic anymore, I don’t believe in the Catholic church, I don’t care for what it represents, and I don’t care to change it because it should be replaced. I even feel that the women who are trying to be part of it, of having a voice there, should reconsider being part of a religion in the name of which millions of human beings have lost their lives (remember the Inquisition, the Holocaust). And yet last February, when I last got together with a CCL group I felt good. But it was the bonding with the women, not Christianity. I have met a woman with whom I have been going for about 6 weeks now and she is a Buddhist. I am exploring her faith, her religion. I have to do now you may ask, Quo Vadis Anno? Ex-nun, ex-cab driver, ex-actress, now future monk? But it is not that bad. Don’t be surprised to find a check in the mail one day. Not as a renewal, but as a sign of support. Because I care for the women of CCL.

How is faith renewed? By unexpected ways. Another woman responded in this way:

“I decided to write a note with my new membership check & tell you about me and why I joined you. I lost my life partner of 17 years, Laurie on April -, 198- to ovarian cancer. She and I had met as Little Falls Franciscans and lived together after we left the religious community. We remained closeted in our work places but built friendship (including many ex-nuns) & family support throughout those 17 years together. When Laurie was dying, last Feb. she wrote her funeral liturgy & there was no doubt that it would be a Catholic/Franciscan ceremony. She incorporated religious songs she loved, wrote her petitions wherein I was proudly recognized as her life partner, had Offertory gifts brought up including our ring, symbolizing our life together & gave instructions on her homily, making sure that I was recognized and a part of it. The church held 400-500 of our families (hers & mine), friends & co-workers who flew in from 8 states. Laurie used the Catholic ritual of the Mass to stay farewell to us and give our lives together respect & honor. I share this with you because if you had heard Laurie & me discuss the Catholic Church throughout the years you would have heard criticism, disgust, sarcasm & hurt over our unacceptance as lesbians & our second class status as women. We talked often of a church we wanted to support & grow in but for that growth we began to look elsewhere. Now I am grateful to the Church for the gift it has given me through its ritual & music, which Laurie used to say good-bye & which she transformed for us as a final tribute to all that she loved. It – the Church – came through for us in the end. My best wishes to you as you continue to publish issues that need to be dealt with, as you encourage community & foster individual spiritual-human growth.”

For many decades my faith as flickered as a tiny candle in a dark cold night. I could never understand why it did not go out, but it never did. One time on retreat, the woman who was my spiritual director asked me how I could call myself “Catholic” when I never went to church or received communion. I can’t recall my answer, but it was probably something like I couldn’t stand the church, but I felt connected to experiences and values growing up and at school. But, her comment bothered me, because some part of it rang true.

Some years after that comment, acknowledging there was a place inside of me that was empty and lonesome, my life partner, Lori (now my wife) and I began attending our neighborhood church in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn. We registered as a “Family.” As such, we received a box of weekly donation envelopes with both our names on it. Our good friend, Sr. Jeannine Gramick of New Ways Ministry, used our comment – “You know you’ve really made it when both names on are the envelope” in her film, “In Good Conscience.” We thought it was quite funny, but it was also quite an acknowledgement.

After some weeks of attending Mass regularly, we volunteered to help out on the social justice committee, and sold Fair Trade coffee after Mass. We made a lot of good friends, and got to know people and they got to know us. Participation in the weekly liturgy, the good community, volunteering with others, the works of charity, and being reminded of other needs besides my own, helped me to return and belong more fully to my faith.

I still and will always have trouble with the sexist language and the way some bishops and church officials pound away over issues like gay marriage. But, in our church, we both have a place. Doubt and Discouragement are my ever-present companions in the pew every Saturday at 4 o’clock Mass, but they have to move over to make room for Hope and Faith.

Kirkridge An unmet need for connection, support and affirmation was the spark behind the Conference for Catholic Lesbians (CCL) held at Kirkridge Retreat Center in November 1982. At that time, no Catholic women’s or gay organization spoke sensitively to the needs of Catholic lesbians, or in many cases, even acknowledged our existence at all. Except for a small presence in Dignity, we were invisible and voiceless.

The goal of the first conference was to come together with others who identified as Catholic and as lesbian; but also to articulate how these two identifications were often at odds in our church, in the gay and lesbian community, and in us. To be one, we had to hide the other. This lack of authenticity and wholeness affected every part of our lives and spirituality.

The conference organizers asked the participants what they hoped to get out of the conference. Among the major themes were the following:

-A greater understanding of myself as a Catholic lesbian; establish friendships with other lesbian women who treasure and nurture their spiritual selves; support and direction.

-A renewal of my Catholic faith and a way to combine it with my lesbianism to a workable balance.

-Prayer & community in a supportive environment. For three years I experienced those elements as a Sister of Mercy. Though it’s been five years since I left the community, the prayer, community and supportive atmosphere are still missed.

-Sharing ideas and experiences with other women of the same background and philosophy in an atmosphere of openness and acceptance. To be able to be proud of being a Catholic and a lesbian without punitive consequences.

-An answer to the question, “How can one be a sexually active lesbian and a Catholic?”

-Help toward resolving my indecision if a lesbian can be Christian, much less Catholic.

-To meet Catholic women, get a better view of women (gay) in the church and learn how to incorporate my Christian gayness in the straight world without becoming bitter.

-A sense of reassurance that Catholic lesbians have not abandoned the church; that God is an integral factor in other lesbians’ lives. An opportunity to discuss Catholicity with other lesbians.

-A greater appreciation of my place in the gay community as a deeply committed Christian woman.

-Meet new people, gain new insight, broaden my thinking and have fun.

-The opportunity to meet and talk with other Catholic lesbians. To share feelings/common problems. To be quite honest, just to be able to do something as a group of Catholic lesbians to come away with a feeling of belonging. That there really are more Catholic lesbians out there than the 1 or 2 we see at church occasionally.

Kirkridge vista What emerged from that weekend gathering was the realization that although there are many ways to identify as being Catholic or lesbian, we shared a bond to a faith with which we would always feel connected, even if we ceased to consider ourselves practicing church members.

What was special about Kirkridge and subsequent conferences was the opportunity to meet, hear and speak with other Catholic lesbians about shared gay experiences, especially the pain that often comes from a sense of rejection and exclusion. As one participated noted, “It is very rare to find lesbians who will own the fact that they have been/are part of the Catholic church. I hope to gain knowledge of other women’s experiences in order to share the past, and deal with the present with a new vision.”

Next: Chapter 2 – Anger and Sadness

Read the entire article here.The Importance of Being Who We Are3

I last saw Ed at the Christopher Street Festival in June 1988. Several dozen Conference for Catholic Lesbian marchers ended up at our booth in front of St. Veronica’s, we did a brisk business selling tee-shirts, buttons and handing out literature. It was a fun and exhilarating day. By connecting with the group and other Catholic lesbians, visitors were able to start to reconcile, or begin to come to terms with, the struggle of faith and sexuality. What they didn’t think was possible did exist.

Ed died of AIDS on February 28, 1989. His last job was at Trix, a gay hustler and strip bar in Times Square. A brief obituary appeared in section B, page 16 of the March 2, 1989, edition of The New York Times: “Edward Francis Murphy, a leader in the gay rights movement, died Sunday at St. Vincent’s Hospital in Manhattan. Mr. Murphy, who was 63 years old and lived in Manhattan, died of heart failure, said his longtime friend, Richard Mahoney. Mr. Murphy became a gay-rights advocate in the 1960s and founded the Christopher Street Festival, held annually the last week in June. He was the director of the One-to-One program at the Manhattan Development Center, a state institution for mentally retarded and developmentally disabled adults. Surviving are his mother, Dorothy, and a sister, Dorothy King, both of Queens. A memorial service is to be held today at 10 A.M. at St. Veronica’s Roman Catholic Church, 155 Christopher Street.” When Ed was arrested for his role in the “Chickens and Bulls” extortions he was living at 167 Christopher Street, close by St. Veronica’s.

St. Veronica’s Church, Christopher Street, NYC At Ed’s standing-room-only funeral, the priest remarked, “If Ed Murphy is not with God, then there is no God.” As pallbearers carried him to the hearse, a police escort stopped traffic and a tenor sang, “Danny Boy.” His obituary in the New York Native, a popular gay newspaper, described Murphy as “a patriarch to his own,” and said that “bigotry appalled him.” He was, the obituary stated, “a humanitarian with few peers whose like may not pass our way soon.” A few months later, Ed Murphy was named posthumous Grand Marshall of the 1989 New York City Gay Pride parade. The Cadillac Murphy traditionally rode in led the march, empty except for the driver.

I do remember that there was some opposition to him being named Grand Marshall. I didn’t know or can’t recall why some people didn’t want him honored—it was never stated clearly. I didn’t understand why people would object. It seemed to me that he did a lot for the gay community. Because he talked to me about it, I knew that Ed had a rough background between jail and jail violence. He spoke in a gruff, New Yawker way, but he was a good man and tried his best to help people. I appreciated what he did for us, and I was fond of him. At no time did I ever hear in conversation or read in gay papers about the Mafia involvement in Stonewall, or Ed’s past life as an extortionist and blackmailer.

In 1989, there were still lots of people around who knew Ed’s awful history. But not one word was written until author and journalist William McGowan’s ground-breaking article in the Wall Street Journal, “Before Stonewall” published on June 16, 2000; over a decade after Ed’s death. Why didn’t anyone come forward? Why was this information suppressed? Here’s one theory: people were afraid. If Ed was able to skate through the “Chickens and the Bulls” without going to jail—blackmailing rich, influential men—who was protecting him? What and who did he know that kept him walking around free? People who might have acted or spoken out chose discretion to save themselves a bad beating or worse. Whether this influence was true or not people believed that it was true and were afraid of him.

The silence regarding Ed Murphy is reminiscent of the silence surrounding the 1965 murder of Malcolm X. Decades later it came out the NYPD and FBI were involved in keeping track of Malcolm X using Black Muslim informants. Some members of the Nation of Islam also knew who the real killers were but didn’t say anything and let two innocent men be convicted and go to prison. Why? I believe that it was to protect themselves and their families from violence and to protect the reputation of the Nation of Islam. The reluctance that minority groups have toward exposing despicable deeds by their members is a defensive reaction to avoid more contempt and oppression by law enforcement and the public. It was better to forget than pursue justice. Like Ed Murphy, at least one of the killers hid in the open and volunteered for a lot of neighborhood charitable activities.

Ed Murphy had resentments and hostilities of his own, including a class resentment of affluent white men. “I resent the George Segal statue created in memory of Stonewall because those people in the statue don’t represent the people who fought back at Stonewall. Those are Fire Island guys in that statue. Those who fought were drag queens, Hispanics, street people.”

George Segal Statues, Greenwich Village, NYC Ed’s statement is true about the Stonewall Riots, but not about Gay Liberation. The latter was mostly the result of large numbers of middle class and affluent whites who came out, organized politically, and demanded change. White gay men, with their contacts and careers in business, law, media, arts, and the entertainment industry pushed hard, particularly with AIDS and later with marriage equality. Back in the late ‘70s, journalist Arthur Bell remarked on the discordant styles of Ed Murphy and the rising cohort of gay activists: “Then there’s his age, and his background, grating against the media image perpetuated by the Dewar’s White Label liberationists. It’s not right for the movement that the boss downtown looks as if he just stepped away from the crap game in Guys and Dolls. That Skull may embody gay liberation is difficult for them to perceive.” And his habit of referring to his “brothers” as “queens, cocksuckers, fags, and worse.”

Ed’s early class consciousness—like Trump era blue-collar resentment of elites—made it easier for him to shake down Wall Streeters and other professional men. He saw them use and discard prostitutes and return to their comfortable if closeted lives. Why not use them to make some money?

On the surface, it appears that after the Stonewall Riots, Ed Murphy experienced a metanoia like St. Paul on the road to Damascus. Before Stonewall, he victimized gay men as part of a money-making scheme; afterwards, he represented himself as one of few Stonewall habitues who really cared about gay rights. He continued to work in gay bars and clubs and expanded his large network of contacts and associates in the gay bar culture. He also became an active volunteer with mentally handicapped and disabled children and adults. By all accounts, he was very gentle and loving with them. Murphy also helped runaways, people with AIDSs and prostitutes who were broke and needed kindness and some cash. “When I was in jail,” he told a reporter, “a lot of people helped me. I’m trying to help somebody back.”

I asked my wife, Dr. Lori Mei, a social psychologist, how Murphy made such a complete change from brute to saint. “I don’t think that he necessarily did,” she said, “he just followed the money. He couldn’t continue to blackmail people; he was too identified at that point, but there was money to be found in charity and gay rights work.” Not as much money as in blackmail, but certainly enough to cobble a living between that and bar work. I think he also took pride in helping people out and was protective of people that he perceived as forgotten, scorned or unwanted.

Ed Murphy never expressed any regret for his role in the “Chickens and the Bulls” extortions or regret for the fear and misery suffered by his victims. Some saints led lives of depravity, but at some juncture expressed remorse for the evil they had done. “I ask Skull if he feels that he’s negating the bad in his life by doing good deeds,” said reporter Arthur Bell, “be it with the gay liberation movement, the crime commission, or the retarded.” “I don’t look at it that way,” Murphy answered. “My past is behind me. I was a crazy kid. I did crazy fucking things. I’m happy with what my life gave me.” Some people acknowledge their responsibility; some justify their misdeeds, others like Ed Murphy shrug them off and move on.

Ed Murphy, the Mafia at the Stonewall, and the “Chickens and the Bulls” scandal are pretty much forgotten today. That’s a shame. The shadowy interactions of these players shaped important episodes in gay, New York, and national history. What happened after Stonewall is the legacy of decades of mistreatment and contempt, and the need for homosexual men and women to lead a double life of quiet desperation. Men could satisfy their need for sex with prostitutes and one-night stands; many women had to be satisfied with close friends and fantasies. For centuries men caught with male prostitutes or decoys have been preyed upon by criminals. Since Ed Murphy procured and pimped, he was in a good position to blackmail.

The Stonewall Riots were a spontaneous public explosion by drag queens, teenagers and bar patrons who were fed up with being pushed around by police and exploited by mobsters. Gay Liberation started back in the 1950s with the Mattachine Society and the Daughters of Bilitis. It was propelled along by the same civil rights currents as the women’s liberation movement and Black Power but flexed a lot of muscle when middle class and affluent whites “came out” and were no longer subject to extortion. Ed Murphy the blackmailer and activist lit the fuse at Stonewall.

I met Ed Murphy almost 40 years ago. Ed reminded me of my father, a tough Irish city boy who made his own way. Ed was a hard man with a soft heart for people who shared his hardships. But I am also painfully aware of the men that Ed hurt, used, and ruined, especially the long-time Wall Street employees who lost their livelihoods and dignity because of Ed’s blackmail and thievery at Stonewall. “Stonewall” became a liberation icon to lesbians and gays around the world; but to the “old and trusted employees” who were turned out of their jobs on Wall Street because they were gay, and the blackmailed men searching for a way out of their loneliness, “Stonewall” was a source of misery and degradation.

Read the entire article. Ed_Murphy_Gay_Blackmailer_and_Activitist

Primary Sources for this Article

I am deeply indebted and grateful to the following writers for their research, books and articles on Ed Murphy, the Mafia, J. Edgar Hoover, and The Chickens and the Bulls scandal.

Phillip Crawford, Jr., The Mafia and the Gays; Queer Joints, Wise Guys and G-Men. A retired attorney, Crawford is a leading authority on the historic role of the Mafia in gay bars. From 2009 to ? Crawford blogged extensively about organized crime at “Friends of Ours.” The blog was located at http://bitterqueen.typepad.com. One particularly helpful post was “Stonewall Riots: A Gay Protest Against Mafia Bars – June 7, 2010. You can also find him online at https://phillipcrawfordjr.medium.com and his website.

Phillip Crawford William McGowan, Before Stonewall: Scandal, blackmail, a police crackdown. Shedding light on a forgotten case. The Wall Street Journal, June 16, 2000. The Chickens and the Bulls – The rise and incredible fall of a vicious extortion ring that preyed on prominent gay men in the 1960s. July 11, 2012. Mr. McGowan is a journalist. http://williammcgowan.com

Arthur Bell, “Skull Murphy – The Gay Double Agent. Village Voice, May 8, 1978. Arthur Bell (1939-1984) was a writer, journalist and gay rights activist who lived in New York City. Bell was a founder of the Gay Activists Alliance and wrote for many gay and mainstream papers, including the popular column, “Bell Tells” in the Village Voice.

David Carter, “Stonewall: The Riots that Sparked the Gay Revolution. St. Martin’s Press, 2004. David Carter gave a presentation before the United States Civil Service Commission on the History of the Stonewall Uprising and the LGBT Civil Rights Movement on June 7, 2019. His full statement can be read here – https://www.washingtonblade.com/2019/06/12/u-s-civil-rights-commission-reiterates-support-for-equality-act/

David Carter Douglas M. Childs, Ph.D., Professor of History at Penn State University. He has posted thousands of pages of FBI files on gays on his website: https://sites.psu.edu/dougsite/page-2/. He wrote a book, “Hoover’s War on Gays – Exposing the FBI’s ‘Sex Deviates’ Program, University Press of Kansas, 2015.

Anthony Summer, “Official and Confidential: The Secret Life of J. Edgar Hoover.” G. P. Putnam & Sons, 1993. https://www.anthonysummers.com. Summers specializes in investigative non-fiction books.

Karen A. Doherty and Barbara M., Conference for Catholic Lesbians (CCL) members and representatives, spoke and met with Ed Murphy around Gay Pride Day and the Christopher Street Festival – 1983-1988. https://nihilobstat.info/2006/06/10/edward-murphy-of-the-stonewall-inn/

Karen Doherty Additional Books, Newspaper Articles, & Blog Posts

Burton Hersh, Bobby and J. Edgar – The Historic Face-Off Between the Kennedys and J. Edgar Hoover That Transformed America, Carroll & Graf Publishers, 2007

Martin B. Duberman, Stonewall, Dutton, 1993

“Detective at Hotel is Held in Extortion,” The New York Times, August 5, 1965.

“Nine Seized Here in Extortion Ring – Hogan Says Gang Preyed on Homosexuals and Others,” by Jack Roth, The New York Times, February 18, 1966.

“Nationwide Ring Preying on Prominent Deviates – Bogus Policemen Victimize Theatrical Figures – Even Reach Into Pentagon,” by Jack Roth, The New York Times, March 3, 1966.

“3 Indicted Here as Sex Extorters – U.S. Charges Ex-Convicts Preyed on Homosexuals,” by Edward Ranzal, The New York Times, June 1, 1966.

William McGowan “Detective Accused as a Top Extorter,” The New York Times, July 1, 1966.

“Blackmail Paid by Congressman – Victim Among Thousands of Homosexuals Preyed by Ring of Extortionists,” by Jack Roth, The New York Times, May 17, 1967.

“Homo Nest Raided, Queen Bees are Stinging Mad,” by Jerry Lisker, New York Daily News, July 6, 1969.

“Christopher’s Emperor: Mike Umbers,” by Arthur Bell, Village Voice, July 22, 1971.

“Ex-Convict Brings Smiles to the Retarded” by Paul L. Montgomery, The New York Times, March 31, 1975.

“Edward Murphy, 63, A Gay-Rights Leader,” The New York Times, March 2, 1989.

SAGE (Senior Action in a Gay Environment) Newsletter, June 1989, New York, NY.

“Charges of Profit Skimming Roil ’92 Christopher Street Festival” by Peder Zane, The New York Times, June 26, 1992.

“J. Edgar’s Slip Was Showing,” by Murray Weiss, February 11, 1993.

Arthur Bell, 1970 “Partners for Life,” by Sidney Urquhart, Time Magazine, February 22, 1993. A review of the book, Official and Confidential: the Secret Life of J. Edgar Hoover by Anthony Summer.

“The Real Mob at Stonewall” by Lucian K. Truscott IV, The New York Times, June 26, 2006.

“Edward “The Skull” Murphy,” by R. Marc Kantrowitz, The Patriot Ledger, June 24, 2012.

“Half-Century Later, NYPD Apologies for Stonewall,” by Duncan Osborne, GayCityNews.com, June 6, 2019.

“Stonewall – Strange But True,” An Historian Goes to the Movies – Exploring history on the screen. Andrew E. Larsen, https://aelarsen.wordpress.com/2015/10/13/stonewall-strange-but-true/

“The Stonewall Inn,” A Gender Variance Who’s Who, Zagria Cowan, https://zagria.blogspot.com/2011/06/the-stonewall-inn.html#.YL6fyPlKhPZ

“Mafia Exploitation of Kids: Really a New Low?” Five Families of New York City. http://www.fivefamiliesnyc.com/2010/04/mafia-exploitation-of-kids-really-new.html

The website – Not Kansas – particularly “The Gay 60s, 1966-1970″

Douglas Childs

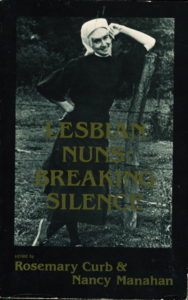

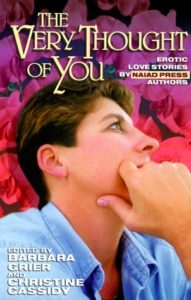

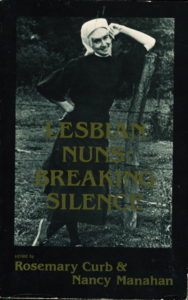

In 1985 the book, Lesbian Nuns: Breaking Silence, was published by Naiad Press. It was an explosive best-seller, thanks to the Boston Archdiocese and Cardinal Bernard Law, who complained about a local television interview with the book’s two editors. The archdiocese described the program as “an affront to the sensitivity of Roman Catholics.” The station cancelled the segment, and sales soared. “This is crazy,” Barbara Grier, a founder of Naiad Press told The New York Times, scrambling to fill orders for the book, “I’m a mouse giving birth to an elephant.” The editors, Rosemary Curb and Nancy Manahan, did have a successful appearance on the Phil Donohue show in April 1985 and went on a national tour for the book. Naiad Press went through four printings of the book, and eventually sold the mass distribution and paperback rights to Warner Books in 1986. Lesbian Nuns eventually sold several hundred thousand copies.

Lesbian Nuns: Breaking Silence included stories by 42 former nuns and women religious, and nine women still in religious life. Most used pseudonyms. All of them wrote about either discovering or acting on their lesbian identity while still in religious life. While there were very few detailed descriptions of sex and seduction, Naiad’s marketing promised to reveal what really goes on behind convent doors, breaking the silence “about erotic love between women in religious life.” While the lesbian religious in the book had affairs or relationships with other sisters, they also fell in love or lust with lay women, married and single. Often the love affair or sexual relationship was the cause of them leaving the convent: it was too hard to maintain a lover relationship and live a religious life. Sometimes the relationships continued but often they did not. I met and knew several of the contributors:

Nancy Manahan, one of the co-editors, worked with the Conference for Catholic Lesbians (CCL) to solicit contributors to the book. She also did a workshop on the book at our 1986 conference. I found Nancy to be a lovely, gracious, caring person.

Susan Weaver was an elegant, elderly woman. We got together several times during my visits to my parents home in Vermont. She made me a beautiful Christmas ornament that I put on my tree every year in memory of her.

Pat O’Donnell was a Dominican sister working at Picture Rocks Retreat house in Tucson, Arizona. She lost her job as the result of her coming out in the book. Pat continued to live and work in Tucson doing spiritual direction.

“Kate Quigley” lived in Montreal and had a long-term relationship with a married woman. The woman’s husband was aware of it. The three of them would go away on vacation together.

Charlotte Doclar worked with Sr. Jeannine Gramick at New Ways Ministry to outreach to lesbian nuns. I met her at a retreat for Catholic lesbians in 1981. Charlotte was friendly, jocular and good-natured. Her story is on the LGBTQ Religious Archives Network.

Dianne Weyers entered her community when she was 14. She left when she was in her late 30s or early 40s with a mysterious back ailment no doctor was able to diagnose but had a crippling effect on her. Since she could not sit upright for long, I typed her manuscript for the book. She felt very unwanted and persecuted by her community, particularly one sadistic superior. I never quite knew what to make of her.

“Sister Maria Nuscera” was a very vivacious lesbian religious in the Midwest. She fell in love and had an affair with a parishioner.

Margaret “Peg” Cruikshank was not one of the lesbian nuns but was one of the driving forces behind the creation of the book. Rosemary Curb and Nancy Manahan, the book’s co-editors, had previously published their own stories as lesbian religious in The Lesbian Path. Peg edited that book and introduced the pair in June 1981. She suggested to Barbara Grier that Manahan and Curb edit a book about lesbian nuns.

The nun on the cover of the book with the “come hither” look was Jean O’Leary, who left the convent and went on to become a co-director of the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force.

The Conference for Catholic Lesbians (CCL), was a group founded in the early 1980s to promote Catholic lesbian visibility and community. Beginning in 1982, the group had advertised and promoted the Lesbian Nuns book project to its members and readers, many of whom were lesbian religious and ex-nuns. CCL’s newsletter editor at that time, a wonderful woman named Pat, knew of Barbara Grier through the Daughters of Bilitis. DOB or Daughters was the first lesbian rights organization in the United States. Pat had been one of the editors of its newsletter, The Ladder. She described Grier as an aggressive, single-minded butch.

The unthinkable happened shortly after the publication of Lesbian Nuns. Barbara Grier, working to maximize income and visibility, offered excerpts of the book to gay and women’s publications like Philadelphia Gay News and Ms. Magazine. She also offered excerpts to Forum magazine; a men’s soft-core porn magazine published by Penthouse. The lead headline in the June 1985 Forum blared in capital letters: SEX LIVES OF LESBIAN NUNS. The lesbian nun stories that Forum bought included “They Shall Not Touch, Even in Jest,” “Finding My Way” and “South American Lawyer in the Cloister.”

Grier justified the decision by stating it would help the book reach a wider audience. She claimed that many women, some of them closeted lesbians, read their male family members’ copies of the magazine. An estimated 15% of Forum readers were female. In an interview with WomaNews, she expressed surprise about the outrage her Forum sale generated— “I had no idea anyone would object.” Even if you are a huge Barbara Grier fan, these two assumptions are hard to accept.

Since CCL had helped to solicit contributors to the book, personally, and through our conferences and newsletter, the organization sent a letter to Barbara Grier protesting the sale of the stories to Forum. We did get a letter back from her a few weeks later. The letter is now lost, but I remember what she wrote. The tone was matter of fact, no apology. She sold the rights to Forum to try to reach as many lesbians as possible. I don’t know if the tiny sliver of lesbian Forum readers would even be interested in the book, but the ensuing controversy certainly helped sales and attracted new customers to Naiad Press. Lesbian Nuns was their greatest publicity tool and best-selling book ever.

Naiad Press was founded in 1973 by Barbara Grier, her partner, Donna McBride, and another couple, Anyda Marchant and Muriel Crawford. The business began with $2,000 provided by Marchant, their first author. She wrote under the pen name, Sarah Aldridge. Over the years Naiad published over 500 books on unconditionally lesbian themes. Mostly romance novels, they included erotica, mysteries and science fiction. Naiad also reprinted some of the most important lesbian pulp novels of the 1940s and ‘50s, including the Beebo Brinker Chronicles by Ann Bannon. Their authors included Jane Rule, Katherine V. Forrest, Claire McNab, Lee Lynch and Karin Kallmaker. Cartoonist Alison Bechdel used to lampoon Naiad books by giving them bar code covers. Grier told Bechdel when she met her that she always loved seeing Naiad jokes in her comic strip. The founders fiercely disagreed over the Forum sale and it precipitated a split a few years later.

In 1973, no bookstores would take lesbian themed books, so Naiad started as a mail order business. Its initial list of 3800 names was the Daughters of Bilitis (DOB), membership list that Grier purloined when the organization folded in 1970. Grier used it to keep publishing The Ladder, DOB’s newsletter, for another two years until funding ran out. Many DOB activists felt Grier stole the list, but she defended her action as necessary for the magazine’s continued existence: “DOB was falling apart—we wanted The Ladder to survive.”

Grier got her start at DOB in 1957 as a book reviewer. Her reviews were written under the pseudonym Gene Damon. She wanted to “nourish all lesbians with books.” In 1968 she became editor of The Ladder. The magazine increased from 25 to more than 40 pages and tripled in subscriptions. She removed the word “Lesbian” from the front cover in order to reach more women. Her makeover was successful but not without conflict. She increased coverage of feminist news, but some DOB members wanted the focus to remain exclusively lesbian. In the late 1960s, the Daughters of Bilitis finally broke under the stresses and conflicts surrounding the political vs. the social aspects of the group; and whether to align with male-dominated gay rights groups, or lesbian separatist feminists. Grier was in the latter camp. The founders of DOB, Phyllis Lyon and Del Martin, leaned more toward acceptance and assimilation.

I skimmed my copy Lesbian Nuns a few months ago, and it spurred me to reflect on what I thought about Barbara Grier now, 35 years after I helped draft CCL’s protest letter to her. I also revisited my 2011 post on Grier, written shortly after she died.

In 1985, I thought Grier was a crud. How could a lesbian publisher sell personal, and often sad and painful coming out stories to a men’s sex magazine? Her goal–to reach as many lesbians as possible- was enough to override every other consideration and objection.

In 2020, my view of Grier is more nuanced. In order to become a successful publisher of lesbian literature in a homophobic world, she needed to be single-minded, relentless and ambitious to endure and prevail. She was a hard worker, tough, and totally dedicated to her ideal of lesbian visibility. “Her goal in publishing,” said Donna McBride, “was to make lesbians happy about themselves.” Books that made lesbians feel secure in their sexual identities were the best. Grier succeeded, and made the world a better place for lesbians. They could see themselves and their lives in books at last.

Grier was also blunt, nasty, calculating, and operated with flexible ethics—think of the Forum sale and the DOB membership list theft. I wonder if she had the idea of starting a book company when she took the list. I bet she did.

As lesbians and gay men continue to integrate into ordinary life and communities, workplaces, parishes, television shows and elected offices, this quote from Grier in 1968 flashes a warning: “When we have amalgamated and homogenized and pasteurized ourselves thoroughly, we can become one of the shapeless, formless, meaningless, ‘walk alike, talk alike, think alike’ things that now live in this country—and then who will write our poetry, our novels of intensity, who will burn a futile fire, howl at the moon aimlessly?”

|