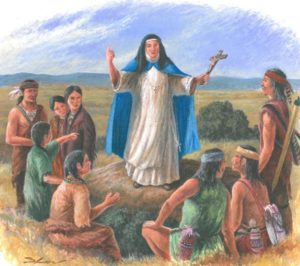

The Lady in Blue

The Venerable Maria of Jesus of Agreda (1602-1665) was an abbess and mystic. Her bilocation between her convent in Spain and native peoples in New Mexico, Texas and Arizona is legendary.

Maria of Jesus spent her entire life within the confines of her family compound in Agreda, Spain. She never left her cloister. When Maria was twelve, her mother converted the home into a convent for herself and her daughters. When she was 25, Maria became abbess of this Franciscan Convent of the Immaculate Conception.

Sr. Maria is mainly known for three parts of her life: an 11-year period of bilocation to New Mexico and Texas; her correspondence of 22 years with King Philip IV and a four-volume work on the life of the Virgin Mary, titled the Mystical City of God. She said the Virgin Mary herself dictated most of the material. She was investigated by the Inquisition several times but exonerated. Her friendship with the king may have been an important factor in ensuring that outcome.

Maria said she first visited New Mexico in 1620. It was the first of more than 500 journeys or flights, sometimes as many as four in one day. They continued until 1631. She did not know whether she traveled in the body or out of body. They started when she expressed a desire to see and evangelize the native peoples. They stopped, she said, when they had access to baptism and the Eucharist.

She spoke to people in Spanish but was understood. She understood the languages native peoples spoke to her. Because they did not know her name, they called her “The Lady in Blue” because of the blue cape or mantle she wore over her habit.

Sr. Maria was able to describe the plants and animals there, as well as the way people dressed and painted themselves. She described one landscape she visited as a place where two rivers meet. In San Angelo, Texas, the Middle Concho River is joined by the South Concho River. The current bishop of San Angelo, Bishop James Sis, said many of the native people in the area who are Catholic have a strong devotion to the Lady in Blue.

In 1690, Franciscan priest Fr. Damian Massanet helped to create San Francisco de los Tejas, the first mission in east Texas. In a report to the Viceroy, he relates an incident that took place during the expedition. While they were distributing cloth as gifts to the local people, their chief or “governor” as Fr. Massanet called him, asked for a piece of blue baize. He wanted to use it as a shroud to buy his mother when she died. Massanet writes, “I told him that cloth would be better, and he said that he did not want any other color than blue. I asked then what mystery was attached to the color blue, and the governor said that they were very fond of blue, particularly for burial clothes, because in times past a very beautiful woman visited them there, who descended from the heights, and that this woman was dressed in blue and that they wished to be like her.”

Two reports of a nun teaching the native people about Christ and Christianity reached the Archbishop of Mexico, Francisco Manzo y Zuniga about the same time. One report was from Maria’s confessor, Friar Sebastian Marilla, who contacted the Archbishop to learn if Maria’s report to him that she had mystically traveled to the southwest was true. The other report came from missionaries in the territory who related how the natives sought them out under the direction of a Lady in Blue. To determine the truth of the reports, the Archbishop assigned Friar Alonso de Benavides to investigate. Friar Benavides had arrived in New Mexico in 1626. He was a Franciscan priest of Portuguese descent. Charged by his order as Custodian (head) of the missions, Benavides toured New Mexico extensively, overseeing the establishment and strengthening of missions.

In 1629 Benavides was sitting outside the Isleta Mission (south of Albuquerque, New Mexico) when a group of 50 natives from an unknown tribe approached him and asked that he send missionaries to their territory. The travelers were Jumanos, and they had traveled a great distance from a place called Titlas, or Texas. The Jumanos said a woman dressed in blue had appeared in their midst and had taught them about the Jesus Christ and the Christian faith. She told them to ask for further instruction and baptism from the Franciscan missionaries. They knew where to find the Franciscan friars from the directions given to them by this Lady in Blue. Two missionaries were sent back with the Jumanos. The friars found the people well instructed in the faith and baptized the entire tribe.

Friar Benavides included this story in his famous 1630 Memorial, or report, which he personally presented to King Philip IV of Spain. This history of Spanish activity in the southwest included descriptions of the geography, culture of the native peoples, evangelization efforts, and the impact of contact with Spanish clergy, settlers and soldiers. Benavides praised the abundant wildlife, arable land and potential mineral wealth of New Mexico. It was a successful fund-raising document. King Philip IV continued to fully fund Franciscan missionary efforts in the region.

Benavides visited the abbess in Agreda in April 1631 and interviewed her over a period of three weeks. He wrote “she convinced me absolutely by describing to me all the things in New Mexico as I have seen them myself…She told me so many tales of this country, that I did not even remember them myself, and she brought them back to my mind.” He even obtained the habit she wore when she went there. “The veil radiates such a fragrance that it is a comfort to the spirit,” he wrote.

Friar Benavides is primarily remembered for his 1630 Memorial which included the first mention of the Lady in Blue; and for bringing the religious statue of La Conquistadora to New Mexico. On February 12, 1634, he presented Pope Urban VIII with a revised copy of his Memorial. In that edition Benavides urged that New Mexico be given its own bishop and a cathedral built in Santa Fe. He actively lobbied for that appointment. Instead, for some unknown reason, he was appointed as the new auxiliary bishop for the Portuguese colony of Goa. Benavides was last seen in Lisbon, taking ship for India. After that, he disappears from history. He may have died crossing the Arabian Sea.

Another written testimony to the presence of Sr. Maria among the natives in Arizona comes from Captain Juan Mateo Mange, who traveled with Jesuit priests Eusebio Francisco Kino and Adamo Gil on the expedition to the Colorado and Gila rivers in 1699. The explorers questioned some elderly natives and asked whether they had heard stories about Don Juan de Onate, who passed through their region with soldiers and horses around 1606. The people told the Spanish that they could remember hearing of such a group from the old people who were now dead. They added—without any prompting—that when they were children a beautiful white woman, dressed in white, brown and blue, with a cloth covering her head, had come to their land. She had spoken, shouted and harangued them…and showed them a cross. Warriors had shot her with arrows, leaving her for dead. She revived and disappeared into the air. They did not know where she came from or lived. After a few days, she returned again and then many times after to speak to them.

Sr. Maria only mentions her bilocation in two documents written almost twenty years apart. The first was a 1631 letter to Franciscan missionaries working in New Mexico to encourage them in their efforts to convert local people. She described her visits to native communities and the resistance to conversion by some members of these communities which feared Christianity as a source of evil. On several occasions the natives turned on her, and shot arrows at her, leaving her for dead. She said she felt the pain of the attacks, but when she would come to herself later in the Agreda convent there was no sign of wounds.

In 1650, Sr. Maria described her mystic journeys in a letter to Bishop Pedro Manero of the Inquisition. In her letter she attempted to clarify some of the information included in Friar Benavides Memorial (or report) published in 1631. She argued that some of the descriptions he included were not false but had been exaggerated. She always maintained that she was unsure as to whether she had traveled in corporeal form or only in spirit, or whether it may have been an angel disguised as her.

Is there any truth to Sr. Maria of Agreda’s claims?

The native peoples of the southwest U.S. and Mexico had extensive trade and travel networks. They also had contact with Spanish explorers, soldiers and religious since the 1530s—almost 100 years before Maria’s spiritual journeys. It is probable they heard stories about Catholic beliefs, practices and veneration of the Virgin Mary. The Blessed Mother is often portrayed wearing a blue cloak in statues and art. Cabeza de Vaca and his fellow shipwreck survivors, Esteban, Alonso Castillo and Andres Dorantes, sojourned with the Jumanos and other Pueblo peoples in their trek from Texas to Mexico. They undoubtedly used Catholic prayers and blessings as part of their healing ceremonies as shaman-doctors.

Could the natives have witnessed a Marian apparition, like Our Lady of Guadalupe, or heard stories about Our Lady of Guadalupe? She was also a beautiful woman dressed in a blue cloak. She appeared to Juan Diego several times in 1531. Stories of this apparition could have made their way north to other peoples.

Another Spanish nun, Mother Luisa de Carrion (1565-1636) also claimed to have undertaken many visits to the native people of New Mexico. Could it have been her? In 1629 her cross was carried by Franciscan priest Francisco de Porras to a mission he established at Awatovi among the Hopi. Mother Carrion fared less well with the Inquisition than Sr. Maria with her bilocation journeys. She was forced to have her tongue measured “to determine if it was short, like a witch’s.” The political tensions and social fissions Fr. Porras caused by his proselytizing were resented by many tribal elders. Poison was suspected when he died in 1633.

Sr. Maria may have heard stories about New Mexico, the native peoples and Franciscan missionaries from travelers, pilgrims and others who visited Agreda. I’m sure she yearned to go herself, but she was confined to a convent. In liminal space during prayer, Sr. Maria either took flight in her imagination, or really made the trip herself, bilocating to Texas, New Mexico and Arizona. I believe Sr. Maria bilocated at least once, traveling to the Jumanos people of Texas to direct them to the Franciscan missionaries to be baptized.

Who is the Lady in Blue? Was it Sr. Maria of Agreda; an apparition of the Virgin Mary, or a composite legend with its root in an ancient mystical event? Whatever the truth may be, she is an incongruous figure: a venerated woman in indigenous folklore, and a useful evangelist who helped promote Spain’s colonial ambitions in the 17th century southwest.