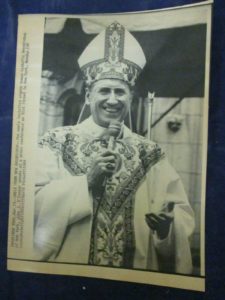

Meeting Archbishop John J. O’Connor

John J. O’Connor, Bishop of Scranton, Pennsylvania, arrived in New York City in January 1984. He was named Archbishop of New York shortly before his installation and made a cardinal by Pope John Paul II in 1985. O’Connor stayed in the news, and in the center of multiple controversies until he died in 2000. He was very passionate about several issues, particularly opposition to abortion and support of organized labor. He also didn’t mince words about lesbian and gay people: no hiring, housing, or civil rights protections. From the start he was a relentless foe of Mayor Edward Koch’s Executive Order 50, a directive which prohibited “agencies that receive city funds from discriminating against homosexuals in employment.”

Although he denied it, O’Connor pressured Francis Mugavero, Bishop of Brooklyn, to shift his diocese’s stance of engagement with gay people to stiff opposition to legal protections. In February 1984 they issued a joint statement in which they claimed that the gay rights bill was “exceedingly dangerous to our society,” explaining, “We believe it is clear that what the bill primarily and ultimately seeks to achieve is the legal approval of homosexual conduct and activity, something that the Catholic Church, and indeed other religious faiths, consider to be morally wrong. Our concern in this regard is heightened by the realization that it is a common perception of the public that whatever is declared legal, by that very fact, becomes morally right.”

Archbishop O’Connor was very clear on his position about homosexuals in the church’s employ–“We have said repeatedly that we have no problem whatsoever in employing people admitting to or not admitting to homosexual inclinations. If an individual avows engagement in homosexual activity, then we want to be able to say whether or not we will employ that person in this particular job, and we feel this is a perfectly appropriate thing for any agency. You know, we have five thousand, seven hundred youngsters in child-care agencies, and they are the ones currently at issue.” O’Connor said it would be wholly alien to Catholic teaching to employ in a child-care agency someone who openly advocated homosexuality.

In September 1984, I was a member of a delegation from the Coalition for Lesbian and Gay Rights (CLGR) who met with Archbishop O’Connor at the New York Catholic Center to discuss Executive Order 50. Terrence Cardinal Cooke, O’Connor’s predecessor, had refused to meet with Dignity/New York to discuss it. Coalition representatives were packed with Catholics, some of whom were members of Dignity and the Conference for Catholic Lesbians (CCL). When we arrived at the building, all in business attire, the guard at the door waved us through saying, “This way, ladies, or whatever…” As we got on the elevator, someone who knew who we were and where we were headed whispered, “Good luck.”

We were ushered into a conference room to wait for Archbishop O’Connor. I had a seat toward the end of the table facing the door. I saw Archbishop O’Connor striding down the corridor towards the meeting room. He was alone; no aides accompanied him. He looked grim. I don’t know what possessed me, but I winked at him. He winked back! We smiled. O’Connor walked into the room and walked around the table shaking everyone’s hand. I thought, “Perhaps there’s hope.” He sat down and the meeting started.

I can’t remember what was said, but all our arguments and personal experiences of ridicule, threats, and rejections by our friends, family, co-workers and faith based on our sexual orientation didn’t affect him. He said something to the effect that the Church would never accept us in the way we wished to live. The table went totally silent. It was a stunning moment; I felt the pain from his statement totally wash over me. I cried. Several other people at the table also cried, including a man who had recently lost his children in a custody battle. I turned to look at Archbishop O’Connor and saw that he looked surprised. He may have thought that our firmness and anger at our Church meant that we hated it or didn’t care. The opposite was true. There was nothing else to say and we left.

A few weeks later, I decided to write him a thank you note for the meeting. I told him I appreciated that he met with us and listened to what we had to say. I also said that while we strongly disagreed, I had respect for him for his straightforward expression of what he believed.

Three weeks later I received a reply to my letter.

Dear Karen:

Your letter…was extraordinarily kind and touched me deeply. I am indeed grateful. It is my sincere hope and prayer that through the years ahead I will be able to serve you in some way that you will consider helpful. My convictions about Church teaching are very deep. I do not anticipate a change in such teachings, and neither do I see it precluding our loving one another as brothers and sisters in Christ.

Please believe that I will give deeply sincere consideration to any recommendations that can help us in that regard in accordance with the tenets of the church which I am certain we both love.

You and your associates are very much in my masses and my prayers, and I ask that you keep me in yours as well.

Faithfully in Christ,

John J. O’Connor

We never spoke, or saw one another again, but the experience of meeting Archbishop O’Connor helped to guide me on how to engage with others with whom I don’t agree:

-Listen to adversaries as well as friends. One discussion may not change any minds, but it will have an impact and it shows a basic respect and courtesy.

-Look for the good in people. See a whole person, not just an opinion or point of view.

-Persevere. The Coalition members at the O’Connor meeting continued the fight for gay and lesbian civil rights. Dignity and CCL continued to work for the respect and recognition of lesbian and gay people in the Church.

On March 20, 1986, the New York City Council passed a homosexual rights bill by an unexpectedly wide margin of 21 to 14. The bill forbade discrimination based on sexual orientation in housing, employment, and public accommodations. The bill did provide an exemption for religious institutions.

The fear that the Archdiocese of New York expressed came true: public protections guaranteed by law did change public perception of lesbian and gay people. The widening acceptance and protection encouraged people to live and love more openly. As more and more gay people came out to their friends, family and colleagues, media portrayals also changed, which encouraged even more people, and younger people, to come out.

In 2013, even the highest level of the Church changed. In response to a question from the news media about a gay priest, Pope Francis made the statement, “Who am I to judge?”