The Church’s Own Gender Bending: The Castrati

Many church officials are going nuts over transgender people calling them unnatural, delusional, or a fad. Male and Female He Created Them: Towards a Path of Dialogue on the Question of Gender Theory in Education, was issued by the Vatican’s Congregation for Catholic Education on June 10, 2019. The document brands changing understanding toward gender identity and sexuality as a cultural and historical trend in “gender theory” that is contrary to the teachings of the Catholic Church.

How does the Vatican explain its own “gender theory” creation–the Castrati? As with most sexual and religious issues in Catholicism, misogyny is at the bottom of it.

In 1588, Pope Sixtus V banned women from singing on stage in any public theater or opera house. They were already banned from singing in church by the Pauline dictum “mulieres in ecclesiis tacesant” (“let women keep silent in churches” 1 Corinthians, ch.14, v. 34). In 1589, in response to a demand for feminine voices to hit the high notes, Pope Sixtus V published the bull Cum Pro Nostro Pastorali Munere, reorganizing the choir at St. Peter’s Basilica specifically to include castrati. The pope was aware the public craved the “voices of angels.”

The process of castrating promising young boys to compensate for the loss of female sopranos became prevalent. This surgical manipulation of nature preserved boys’ high youthful voices although they had the vocal power of men. The promise of lucrative careers persuaded many poor Italian parents to castrate their sons if they possessed musical talent. It is believed that many operations to remove testicles were carried out by slitting the groin and severing the spermatic cord. Some boys could still achieve an erection depending on the age they were castrated.

Castrati were sexually attractive to members of both sexes. Because male castrati could not procreate, women found them particularly attractive as casual sex partners. Castrati developed the reputation of having enhanced sexual prowess due to their lack of sensation.

According to a story by author Tony Perrottet, even the famous Casanova was tempted. “Rome forces every man to become a pederast,” he sighed in his memoirs. His most confusing moment came when he met a particularly lovely teenage castrato named Bellino in an inn. Casanova was bewitched, going so far as to offer a gold doubloon to see the boy’s genitals. In an improbable twist, when Casanova grabbed Bellino in a fit of passion, he discovered a false penis: it turned out that the castrato was a girl, who historians have identified as Teresa Lanti. She had taken up the disguise to circumvent the ban on female singers in Italy. She later “came out” to perform in other European countries which did not have restrictions on female singers.

In the 17th century thousands of boys between the ages of 8 and 12 were castrated annually. While there is no exact figure, 80% are estimated to have survived the surgery. A lucky few became celebrities. The rest festered in small church choirs or became prostitutes or beggars. The castrati often grew up with feminine features and smooth, hairless bodies. Some of them were tall and gangly, others grew breasts and heavy buttocks. Castration for the sake of art was finally banned in the early 19th century. However, Italian doctors continued to create castrati until 1870. The Vatican employed them as singers in the Sistine Chapel until 1903. In truth, the church condoned—or looked the other way—when adolescent boys were castrated in order to produce males with soprano voices.

In the 1993 book, Engel wider Willen: Die Welt der Kastraten (Angels Against their Will) German historian Hubert Ortkemper said the castrato Alessandro Moreschi (1858-1922) performed in the Sistine Chapel until 1913. Moreschi lived long enough to make recordings in 1902 and 1904. You can listen to him sing, “Ave Maria” here.

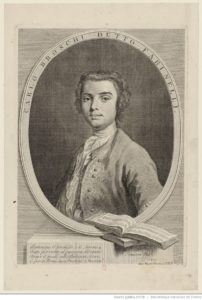

The most famous castrato, Carlo Broschi, was born in a small city in Southern Italy in 1705. Better known by his stage name Farinelli; he became the greatest opera singer of the 18th century, performing all over Europe. His stage career lasted from 1720 to 1737. He outlived most of his contemporaries and died in Bologna in 1782. In 2006, Farinelli’s remains were exhumed to be moved to another cemetery. Scientists and antiquarians took the opportunity to study the effects of castration on body development. They discovered osteoporosis and a condition called hyperostosis frontalis interna in Farinelli’s bones. These conditions are common in older, post-menopausal women.

In his mind-blowing article “Some Men Are Born Eunuchs” former Providence College professor, Anthony Esolen, compared the castrati operations to the process of transitioning from male to female (transwomen). His verdict: “However sick it was to do that then; it is far sicker to do what we do now.” According to his reasoning, a castrated boy at least produced a beneficial outcome; a beautiful voice for art or liturgy, financial security, or social status. “He” would still be a “he.” In contrast, the “mutilation” a transwoman endures to achieve feminine characteristics does not produce a beneficial outcome, only a freak who was “troweled out for a mock vagina.” “He” wants to become a “she.” Esolen’s article is obviously meant to defend the Church’s position on gender changes and transsexuals. His loathing of feminists, homosexuals, and transsexuals is evident. But in his haste to condemn adult males who chemically and surgically transition to female, he ignores the physical changes of the castrati. They became feminine, too, with high voices, breasts, big asses and soft skin. What is also evident is his delusion that a small boy, 8, 9, or 10 years old could make the choice to be castrated. It wasn’t a noble gesture. They were pushed into the barbershop by their parents or a priest.

The strong whiff of misogyny in the Esolen article is reminiscent of Pope Sixtus V’s decree to ban women’s voices in church and the stage and substitute them with castrati. It appears that it’s better to have males with no balls in the choir than women.