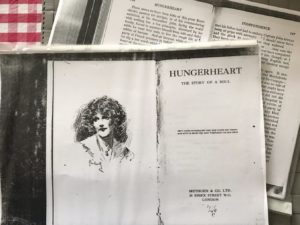

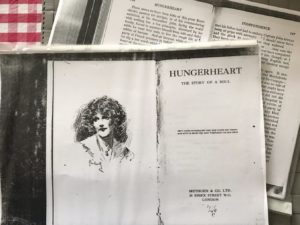

Hungerheart is a lesbian novel written by British author Christabel Marshall under her adopted male name, Christopher St. John. The book was published in 1915 in London by Methuen & Co. The novel is a first-person account of Joanna, “John” Montolivet that follows her search for love and passion. At one point she lives with Sally, a young actress, and they are “happy as a newly married pair, perhaps happier…” Sally decides to marry a man, and Joanna/John finds solace in the arms and bodies of stormy and dramatic women. Eventually she heads for quieter shores, and coverts to Catholicism. Her “friendship” with a young nun fulfills her heart’s hunger. “There are things that can be lived, but not chronicled, and our friendship is one of them,” Joanna/John describes. “Who in the world could understand our moments of union? Who in the cloister either? But they are understood in heaven…Thy love for me is wonderful, passing the love of men.”

Hungerheart never achieved the fame of another book written a decade later by another Catholic lesbian—Radclyffe Hall’s, The Well of Loneliness. Only a few copies of Hungerheart survive in research libraries. For some odd reason, it was not tagged with a homosexual or degenerate label but cataloged as a work about “Catholic spirituality.”

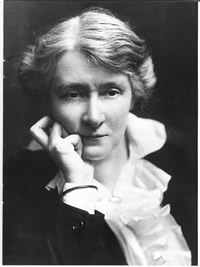

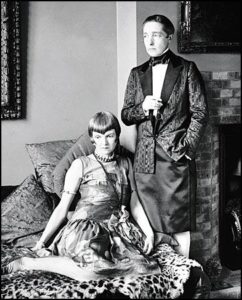

Christabel Marshall

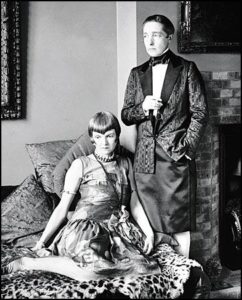

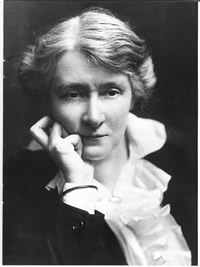

The author’s book embodied her voracious love life. Christine Gertrude Marshall a.k.a. Christopher Marie St. John (1871-1960) was an English suffragette, a playwright and writer. After college, Marshall served as secretary to Lady Randolph Churchill and actress Dame Ellen Terry. Marshall became romantically involved with Dame Ellen’s daughter, Edith (Edy) Craig (1869-1947). The two women began living together in 1899. Marshall attempted suicide when Craig accepted a marriage proposal from composer Martin Shaw in 1903. Edith Craig was an actress, director, producer and costume designer.

In 1912 Christabel Marshall converted to Catholicism and took the name, St. John out of affinity with St. John the Baptist. Her friend, Claire Atwood, converted around the same time. Atwood gave Una Troubridge and Radclyffe Hall, another Catholic couple and close friends, a relic of the true cross acquired by her ancestors from a pope. Una put it with candles and flowers in a shrine in her bedroom.

In 1916, artist Claire (Tony) Atwood (1866-1962) moved in with Craig and Marshall. Their menage a trois lasted until Craig’s death in 1947. Una Troubridge used to call them, “Edy and the boys.” They often wore men’s attire to match their male names. “Miss Craig,” wrote Virginia Woolf in her diary, “is a rosy, ruddy ‘personage’ in white waistcoat, with black bow & gold chain loosely knotted.” Marshall wrote rhat the three women “achieved independence within their intimate relationships…working respectively in theatre, art, and literature, and drew creative inspiration and support from one another.”

Edith Craig

In 1932, when she was sixty-one, Marshall fell madly in love with Vita Sackville-West, a member of the Bloomsbury Group and a successful poet and writer. Their affair continued for several years and caused huge fights between Marshall and Craig. Atwood unsuccessfully tried to serve as a peacemaker.

In 1935, under her male name, Christopher St. John, Marshall wrote a biography of a distinguished physician, Dr. Christine Murrell, the first female member of the British Medical Association’s Central Council. Titled, “Christine Murrell, M.D., Her Life and Work,” St. John/Marshall wrote the dedication to both of Murrell’s lovers: Honor Bone, M. D. and Marie Lawson, a printer, editor, and tax resister. Like St. John/Marshall, Murrell had a threesome household.

Christabel Marshall/Christopher St. John died in 1960. She is buried next to Claire Atwood at St. John the Baptist’s Church, Small Hythe, England. This is the church where Dame Ellen Terry worshipped and where her funeral Mass was held in 1928. Edith Craig’s ashes were supposed to be buried there as well, but by the time of Marshall’s and Atwood’s deaths, they had been lost. A memorial was placed in the cemetery instead.

Why did so many Anglican clerics, creatives and/or socially prominent gays and lesbians convert to Catholicism in the Victorian and Edwardian eras? The Catholic Church has always been opposed to homosexual sex; but it also has been tolerant of gay sex among its members, including priests, the hierarchy and religious, as long as they were discreet and parroted official teaching in public. At that time, being Catholic was a little naughty, not socially acceptable, and showed a streak of rebellion and independence. Creatives were drawn to the sensuousness, the pageantry, and the mysteries in Catholicism. Catholicism emphasizes the body—the body of Christ in our mouth, the bodies of saints who give themselves up to pain and ecstasy, the homoerotic images found everywhere there are Catholic artists and cathedrals. For women, Catholicism offers many role models of women who lived full and fulfilling lives—without men.

Christopher St. John’s Shrine

“Then Stephen took Angela into her arms and she kissed her full on the lips.” That sentence has thrilled tens of thousands of lesbian readers, including me, to finally see, feel, imagine their desire in print. When British novelist Radclyffe Hall (1880-1943) published The Well of Loneliness in 1928, it was the first widely read novel to feature lesbian love. A British court judged the book obscene because of the words “and that night they were not divided.”

It tells the story of Stephen Gordon, a woman given a man’s name by parents that wanted a boy, who is irresistibly drawn to other women. She was born on Christmas Eve and named after the first Christian martyr. As a girl she had a dream: “that in some queer way she was Jesus.” Seven-year-old Stephen develops a crush on the Gordon’s maid, Collins. When she discovers that Collins has “housemaid’s knee” she prays that the affliction be transferred to her. “I would like to wash Collins in my blood, Lord Jesus—I would very much like to be a Saviour to Collins—I love her, and I want to be hurt like You were.” Stephen is later devastated when she catches Collins sharing a kiss with the footman.

As a young woman Gordon has an affair when a neighbor’s wife. After a confrontation with her mother about her “unnatural” love, she retreats to her father’s study and discovers a book by German psychiatrist, Krafft-Ebing, on deviant sexuality. After she reads it, she understands what she is—a female “invert,” a lesbian. She opens a Bible, and seeking a sign, reads Genesis 4:15: “And the Lord set a mark upon Cain…” Radclyffe Hall used the mark of Cain, a sign of crime and exile, throughout the book for the status of “inverts.”

Stephen meets Mary Llewellyn, the love of her life, in France during World War I. The two set out to build a life together, but Stephen believes that Mary’s life is suffering because as a couple they are an object of scorn and contempt. To “save” her, she feigns an affair with another woman to drive Mary into the arms of a man who admires and wants her. Mary leaves her and marries. Stephen is devastated and alone. She has a vision of being thronged by millions of inverts from throughout time, living, dead and unborn. They beg her to speak with God for them. Possessing her, she articulates their collective prayer: “God,” she grasped. “We believe, we have told You we believe…We have not denied You, then rise up and defend us. Acknowledge us, oh God, before the whole world. Give us also the right to our existence!”

Radclyffe Hall was a pioneer in her efforts to reconcile Christianity and homosexuality. Her defense of gay men and lesbians took the form of a religious argument: if God created inverts, the rest of humanity should accept them. Declaring homosexuality to be a “part of nature, in harmony with it, rather than against it.” She posed the question to her attackers: “if it occurs in and is a part of nature, how can it be unnatural?” She also knew the price that gay and lesbian people pay to remain in the closet and railed against the “conspiracy of silence” saying, “Nothing is so spiritually degrading or so undermining of one’s morale as living a lie.”

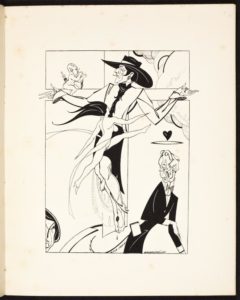

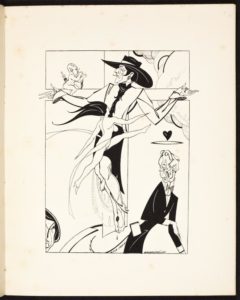

The controversy over The Well of Loneliness was lampooned in The Sink of Solitude, a satirical pamphlet by Beresford Egan, novelist, and illustrator. One drawing shows an immediately recognizable Radclyffe Hall with her trademark Spanish riding hat nailed to a cross. A near-nude Sappho leaps in front of the martyred “St. Stephen” and Cupid perches on the crossbeam. While Egan agreed with Hall’s arguments, he spoofed her piety and moralizing.

Radclyffe Hall is like many Catholic lesbians I have met: conventional, judgmental, spiritual, and often promiscuous.

She was born Marguerite Radclyffe on August 12, 1880 at Christchurch, Bournemouth, England. In later life she was called John by her friends and lovers, and M. Radclyffe Hall or Radclyffe Hall in her books. Her mother, Marie, was an American and her father, Radclyffe Radclyffe Hall, was English. Her parents divorced when she was two and Marie remarried a musician, Albert Visetti. The young girl never liked him. She reached young womanhood without much education or interests except chasing women. Her specialty seems to be the seduction of married women.

In 1907, at 27, unattached and drifting, Hall made a trip to Bad Homburg, Germany, known for its wellness spas and baths. She became smitten with Mabel (Ladye) Batten, a renowned beauty and amateur singer. Batten’s portraits were painted by John Singer Sargent and Edward John Poynter. The 50-year-old married grandmother had ties to aristocratic society and was rumored to have had an affair with King Edward VII. The poet-adventurer Wilfrid Scawen Blunt was an admirer. Witty, elegant, cultured, beautiful and worldly, Batten was everything Hall desired. They became lovers and stayed together until Batten’s death in 1915.

Batten was a major influence on Hall, and encouraged her to write poetry. Hall’s first book of poems, A Sheaf of Verses, published in 1908, reveals her first, tentative references to homosexuality. A second book of poetry including the “Ode to Sapho” was published later that year. Her third volume came out a year later. When Batten’s husband died in 1910, the two women made a home together. Hall’s fourth poetry anthology was dedicated to Batten.

Batten was politically conservative, and Hall adopted her positions. Ladye was also a Catholic convert, and under her encouragement and influence, Radclyffe Hall was received into the Catholic church on February 5, 1912. She was 32. Her baptismal name was Antonia, and she chose Anthony as her patron saint. Hall and Batten worshiped together at London’s fashionable Church of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, known as the Brompton Oratory. In 1913, Hall and Batten made a pilgrimage to the Vatican. They went to Mass at St. Peter’s Basilica. Pope Pius X blessed them in a semi-private audience with other substantial donors. They returned to London with religious-themed triptychs, gilt angels and an alabaster Madonna.

The refined Ladye was both a maternal and wifely figure for Radclyffe Hall. The once-feminine Hall, who wore skirts all her life and only had her waist length blond hair cut in her 30s, started to cultivate a more masculine appearance, close-cropped hair, tailored jackets and bow-ties. Batten gave Hall the nickname “John” after noting her resemblance to one of Hall’s male ancestors. She used this name for the rest of her life. Was Hall butchy, a butch, stone butch, or these days – a transman? It’s hard to say. She said that she had a man’s soul in her body.

In 1915, 35-year-old Radclyffe Hall met Una Troubridge (1887-1963), a 28-year-old cousin of Mabel Batten, at a tea party in London. They were immediately sexually attracted to one another and began an affair. Their relationship that would last until Hall’s death in 1943. Troubridge was a sculptor and mother of a young daughter. She was married to Vice-Admiral Ernest Troubridge, a career naval officer who was 25 years her senior. Hall’s affair with Troubridge caused an uneasy situation among the three women.

In May 1916, Batten suffered a cerebral hemorrhage after a quarrel with Hall over Troubridge. She died ten days later. Guilty and grief-stricken, Hall believed her infidelity had hastened Batten’s end. She had Batten’s body embalmed and buried her with a silver crucifix blessed by Pope Pius X. Soon after Batten’s death, Hall and Troubridge developed an interest in spiritualism and began attending seances with a medium, Mrs. Gladys Osborne Leonard. They believed Batten’s spirit gave them advice.

Most of the stories, poems and novels Radclyffe Hall wrote touched on Christian themes, Catholic imagery, lesbian desire or all three. In 1924, Radclyffe published The Forge, a fictionalized portrait of American lesbian artist Romaine Brooks, and The Unlit Lamp, a novel about a girl who dreams of going to college and setting up a “Boston marriage” with her tutor, Elizabeth. A Saturday Life (1925) follows the life of a girl who takes up and discards many artistic pursuits with the support of an older woman who is in love with the girl’s mother. Hall’s fourth novel, Adam’s Breed (1926) centered on the spiritual struggles of a young man over excess consumption by modern society. He becomes disgusted with his job as a waiter and even with food itself, gives away his belongings and lives as a hermit in the forest. The story also reflect’s Hall’s concern about the plight of animals. The book won the 1926 James Tait Black Memorial Prize for fiction and the Femina Vie Heureuse Prize for best English novel.

In early July 1926 Hall completed the short story, “Miss Ogilvy Finds Herself,” which dealt with homosexuality. Later than month she began writing Stephen, the novel that became The Well of Loneliness (1928). The Master of the House (1932) is an adaptation of the Christ story in a contemporary setting. Christophe Benedict, the main character, is a deeply spiritual and compassionate carpenter who lives in Provence, France. He is born to a carpenter named Jouse and his wife, Marie. Christophe ends up being crucified by Turks in Palestine during World War I. Writing the book was so spiritually intense that Hall developed stigmata on the palms of her hands.

In the 1930s Hall and Troubridge made their home in Rye, a village in East Sussex where many writers lived. Hall used Rye as the setting for the book, The Sixth Beatitude (1936), her last novel. It is the story of Hannah Bullen, a strong-bodied young woman. Hannah Bullen’s unconventional life (unmarried mother of two children) is beset by poverty and strife within her family. Hall uses the sixth Beatitude to portray Bullen’s purity of heart and mind by sticking with them. An independently wealthy heiress, Hall gave generously to the local church. Saint Anthony of Padua was constructing a new building when they moved to Rye. Biographer Diana Souhami wrote that Hall “poured money into the church” to bring it to completion and furnish it. “She paid for its roof, pews, outstanding debts, paintings of the Stations of the Cross and a rood screen of Christ the King. A tribute to Ladye was engraved on a brass plaque set into the floor: “Of your charity, Pray for the soul of Mabel Veronica Batten, In memory of whom this rood was given.”

What is the attraction of lesbian and gay men to Catholicism? Why did so many late 19th century writers, intellectuals, artists, clergy and bohemians (with gay lovers, tendencies or friends) take the plunge into the faith? Notable converts include Oscar Wilde, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Aubrey Beardsley, lovers Katherine Bradley and Edith Cooper, Ronald Firbank, Maurice Baring, Eric Gill, Robert Hugh Benson, John Henry Newman, Frederick Rolfe, Marc-Andre Raffalovich, John Gray; and, of course, Mabel Batten, Radclyffe Hall and Una Troubridge.

Oscar Wilde opined on the attraction of the Roman Catholic Church for outre artistic figures and rebels. He said that Catholicism was “for saints and sinners,” while…” for respectable people, the Anglican Church will do.” Becoming Catholic was an act that allowed one to become both rebellious and steeped in tradition. Irish playwright and novelist Emma Donoghue observed: “Being Catholic in England meant becoming slightly foreign, aloof from the establishment; as a church it was associated with the rich and the poor, but definitely not the bourgeoisie.” For much of English society, to become Catholic was to cross society’s lines to a suspect, “other,” even deviant, religion. But the “otherness” may have been a reason behind its attractiveness.

The sensuousness and eroticism present in Catholic art and ritual have a magnetic appeal to lesbian and gay people. Beautiful men, barely covered; women with their heads thrown back in orgasmic passion—a feast for the eyes and imagination. We can appreciate symbolic and hidden meanings, the emphasis on the body, particularly the Eucharist, where we take the body of Christ into our mouth; and the mystery inherent in ourselves and in the spiritual world.

Modern scholars have explored the role of religion in Radclyffe Hall’s work. Catholic Figures, Queer Narratives (2007) includes the chapter “The Well of Loneliness and the Catholic Rhetoric of Sexual Dissidence” by Richard Dellamora. He explores Hall’s life and work. Ed Madden, English professor at the University of South Carolina, examines Hall’s use of Christ’s imagery and symbolism in Reclaiming the Sacred: The Bible in Gay and Lesbian Culture (2003) edited by Raymond-Jean Frontain.

Like a bee sipping nectar from flower to flower, Hall’s desire for women never waned. Her indiscretions as “man of the house” could be overlooked as long as they were brief. Una Troubridge and Radclyffe Hall stayed together as a couple until Hall’s death in London from colon cancer in 1943. The relationship survived Hall’s numerous flirtations and Hall’s last torrid affair with her 28-year-old White Russian nurse, Evguenia Souline (1906?-1958). Souline was hired to help care for Hall during an illness, and their relationship blossomed into much more. Despite the initial protests of Troubridge, the three women lived together in Florence, Italy. At the outbreak of World War II they left and settled in Devon, England. “Darling—I wonder if you realize how much I am counting on your coming to England,” Hall wrote to Souline, “how much it means to me—it means all the world, and indeed my body shall be all, all yours, as yours will be all, all mine, beloved. And we two will lie close in each others arms, close, close, always trying to lie even closer, and I will kiss your mouth and your eyes and your breasts—I will kiss your body all over—And you shall kiss me back again many times as you kissed me when we were in Paris. And nothing will matter but just we two, we two longing loves at last come together. I wake up in the night & think of these things & then I can’t sleep for my longing, Soulina.” Una Troubridge cannot have been happy reading that note. Even so, much of Hall’s correspondence to Evgenia Souline has been preserved. Troubridge burned Souline’s letters to Hall.

Radclyffe Hall died at her flat in Pimlico on October 7, 1943. She bequeathed her entire estate to Troubridge. At her request, she was buried in a vault next to Mabel Batten in Highgate Cemetery in London. Souline was given a small allowance and disappears from the story. At the time of her death, The Well of Loneliness had been translated into 14 languages and was selling more than 100,000 copies a year. It has never gone out of print. For decades, it was the only lesbian book generally available.

Troubridge, now a wealthy woman, moved to Italy and died of cancer in Rome in September 1963, at age 76. Shortly before Troubridge died, a woman asked her how she and Hall reconciled their relationship with their Catholic faith. What did they do about confession? Troubridge answered, “There was nothing to confess.” Troubridge left written instructions that her coffin be placed in the vault in Highgate Cemetery where Hall and Batten had been buried, but the instructions were discovered too late. She was buried in the English Cemetery in Rome, and on her coffin was inscribed, “Una Vincenzo Troubridge, the friend of Radclyffe Hall.” Years later her tomb was removed and her remains were lost.

The Well of Loneliness has been criticized by lesbians for its stereotypical butch-femme coupling, energetic lesbians who are always masculine looking, and requisite unhappy ending of a love affair or relationship between two women. What is totally ignored is Hall’s Christianity and Catholic faith in her life and writing. A friend once observed to me that it is easier to be a lesbian in the Catholic Church than a Catholic in the lesbian community. Like 19th and 20th century biographers who often left out, or slyly alluded to their subject’s homosexual life; too many “herstory” archivists, writers and editors deliberately omit lesbian religious faith and commitment. This bigotry needs to stop.

“Who are you to deny our right to love” – Radclyffe Hall The Well of Loneliness