Marguerite Porete and Her Killers

The chronicler William of Nangis describes the trial and execution of Marguerite Porete, 1310:

“Around the feast of Pentecost is happened at Paris that a certain pseudo-woman from Hainault, named Marguerite and called ‘la Porete,’ produced a certain book in which, according to the judgement of all the theologians who examined it diligently, many errors and heresies were contained; among which errors (were the beliefs), that the soul can be annihilated in the love of the Creator without censure or conscience or remorse and that it ought to yield to whatever by nature it strives for and desires. This (belief) manifestly rings forth as heresy. Moreover, she did not want to renounce this little book or the errors contained in it, and indeed she even made light of the sentence of excommunication laid on her by the inquisitor of heretical depravity, (who had laid this sentence) because she, although having been lawfully summoned before the bishop, did not want to appear and held out in her hardened malice for a year and more with an obstinate soul. In the end her ideas were exposed in the common field of La Greve through the deliberation of learned men; this was done before clergy and people who had been gathered specially for this purpose, and she was handed over to the secular court. Firmly receiving her into his power, the provost of Paris had her executed the next day by fire. She displayed many signs of penitence, both noble and pious, in her death. For this reason, the faces of many of those who witnessed it were affectionately moved to compassion for her; indeed, the eyes of many were filled with tears.”

Marguerite

Marguerite Porete was a 14th century French mystic who wrote a book entitled “The Mirror of Simple Annihilated Souls and Those Who Only Remain in Will and Desire of Love.” Written during the 1290s, the book was condemned by the French Inquisition as heretical. Marguerite was jailed for a year and a half and asked to recant. When she refused to respond to her inquisitors, she was condemned to death.

The book provoked controversy, likely because of statements such as “a soul annihilated in the love of the Creator could, and should, grant to nature all that it desires,” which some took to mean that a soul can become one with God and that when in this state it can ignore moral law, it had no need for the Church and its sacraments or code of virtues. This is not what Marguerite taught, since she explained that souls in such a state desired only good and would not be able to sin.

Not much is known about Marguerite’s early life, except that she was born in Hainault in what is now Belgium around 1248 or 1250. She lived during different periods in Valenciennes, Lorraine, Reims and Paris. She seems to have been a stubborn woman, determined to share her ideas despite ecclesiastical censure. I don’t know why she refused to speak to her inquisitors during her trial and captivity. It may have been disdain or defiance, or it may have been to induce a similar helplessness and frustration in her persecutors. She refused to participate in an outcome that they had already decided.

Tina Beattie, professor of Catholic Studies at Roehampton University, London, said: “Little is known about Porete, apart from the record of her trial and what can be gleaned from her writings. It seems likely she was associated with the Beguines, a women’s religious movement which spread across northern Europe during the 13th and 14th centuries. Although the Beguines devoted themselves to charity, chastity and good works, they took no religious vows and their lifestyles varied greatly, from solitary itinerants (of which Porete was likely one) to enclosed communities. The Beguines were part of an era of vigorous spiritual flourishing during the Middle Ages. They were condemned by the Council of Vienne (1311-1312), which also condemned the Free Spirit Movement with which the Beguines were sometimes (and probably erroneously) identified.”

Her Killers – Bishops, Inquisitor, King

Gui de Colle Medio (or de Colmier) was bishop of Cambrai from 1296-1306. He condemned The Mirror and ordered it publicly burned in Marguerite’s presence in Valenciennes. She was ordered not to circulate her ideas or the book again.

The next bishop of Cambrai, Philippe de Marigny, made her life worse. His persecutions combined politics and religion. Philippe Le Portier de Marigny was appointed bishop of Cambrai in 1301 and archbishop of Sens in 1309. His half-brother, Enguerrand de Marigny, Baron Le Portier, was the chamberlain and chief minister to Philip IV, the king of France. Enguerrand was influential in obtaining these appointments for his brother. Philippe de Marigny became an important figure in the trials of the Knights Templar, and in the execution of Templar’s grand master, Jacques de Molay. De Molay was burned alive with three other Templar leaders on a scaffold in front of Notre Dame Cathedral on March 18, 1314. He uttered his famous curse, and both King Philip IV and Pope Clement V followed him to death (and judgement) within a year. The new king of France, Louis X, had Enguerrand de Marigny hanged for sorcery in April 1315.

Marguerite Porete’s main persecutor and tormenter was the Inquisitor William of Paris, also known as William of Humbert. This Dominican priest and theologian was the confessor to King Philip IV. Appointed Inquisitor in 1303, William also played an important role in the trials and persecution of the Knights Templar. Interestingly, William died in 1314, the same year as Jacques de Molay, King Philip IV and Pope Clement V. Perhaps Molay included him in his curse.

The piety and politics of King Philip IV helped shape the deaths of Marguerite and the Knights Templar. Many of the enemies of the crown were cast as heretics; a convenient label for a self-appointed defender of the Faith. William of Paris supported the political machinations of the French king by suppressing the Knights Templar. The King aided the Dominican’s interests in ridding him of Marguerite—an independent and potentially dangerous religious voice.

Arrest and Trial

In 1308 William had Marguerite Porete arrested along with a Beghard, Guiard de Cressonessart, who was also put on trial for heresy. Their trial began early in 1310 after they were held in prison in Paris for a year and a half. Under tremendous pressure, de Cressonessart eventually confessed and was found guilty. Marguerite refused to recant, withdraw her book or cooperative with the authorities, refusing to take the oath required by the Inquisitor to proceed with the trial. William was not going to have any easy time proving her a heretic. Marguerite had consulted three church authorities about her writing and gained their approval, including the highly respected Master of Theology Godfrey of Fontaines at the University of Paris. Godfrey’s involvement was an important factor in William’s handling of the trial, requiring him to build his case as carefully as possible. He consulted over 20 theologians—an excessive number–on the question of The Mirror’s orthodoxy.

Death

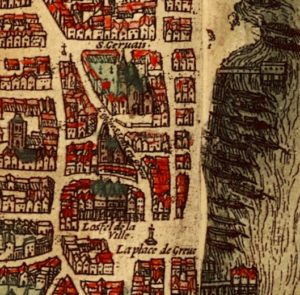

On May 31, 1310 William of Paris read out a sentence that declared Marguerite “called Porete,” a beguine from Hainault, to be a relapsed heretic and released her to secular authority for punishment. He ordered all copies of a book she had written to be confiscated. William called her a “pseudo-mulier” (fake woman) and described The Mirror as “filled with errors and heresies.” William next consigned Guiard de Cressonessart, a would-be defender of Marguerite to life imprisonment. Marguerite condemned to be burnt at the stake as a relapsed heretic. On June 1, 1310 Marguerite was burned alive along with a relapsed Jew at the Place de Greve – today the Place de l’Hotel de Ville – in Paris.

Why Was Marguerite a Target?

There are several possible reasons why so much effort was made to put Marguerite on trial and kill her.

- A growing hostility to the Beguine movement by Franciscans and Dominicans. Beguines were lay religious women who were not under male authority and direction and were outside civic and ecclesiastical structures. In 1311—the year after Marguerite’s death—ecclesiastical officials made several specific connections between Marguerite’s ideas and deeds and the Beguine status in general at the Council of Vienne.

- The popularity of The Mirror of Simple Souls gave Marguerite a prominent profile other lay writers didn’t possess. She also wrote in French, not Latin.

- Marguerite’s perceived association with the Free Spirit Movement or Brethren of the Free Spirit. Free Spirits were not a single movement or school of thought, but they caused great unease among churchman. They were considered heretical because of their antinomian views. One of beliefs some Free Spirits held is that they could not sin by having sexual relations with any person. Extracts of The Mirror of Simple Souls were cited in the bull Ad Nostrum issued by the Council of Vienne to condemn the Free Spirit movement as heretical.

Was there a whiff of homophobia in William of Paris’ denunciation of Marguerite as a “pseudo-woman”?

Marguerite Porete’s era is a mirror to our own. 40 years ago conservative political and religious leaders like President Ronald Regan and Pope John Paul II colluded on major political actions and social change. Lay Catholics began to search for new ways to experience a direct relationship to God. Many of these explorations were condemned since they were outside of traditional structures. The prevailing norms of sexual and gender expression were openly questioned by ordinary people. Sex and sexuality are fraught and fearful topics for the Catholic hierarchy, and many bishops tried their best to suppress them. Their best allies were presidents focused on wealth and expansion. Today, President Trump sounds and acts a lot like King Philip IV.

We can point to one improvement in the last 700 years. We can no longer be burned at the stake.

Further Reading:

Allegories of Love in Marguerite Porete’s ‘Mirror of Simple Souls’ by Suzanne Kocher

The World on the End of a Reed by Francesca Caroline Bussey

The Heresy of the Free Spirit in the Later Middle Ages by Robert E. Lerner

Courting Sanctity: Holy Women and the Capetians by Sean L. Field

Transmitting the Memory of a Medieval Heretic: Early Modern French Historians on Marguerite Porete by Danielle C. Dubois

Marguerite Porete: The Mirror of Simple Souls by Ellen Babinsky