Flannery O’Connor’s Catholic Lesbian Friend

Shortly after A Good Man is Hard to Find was published, a discerning reader in Atlanta wrote to author Flannery O’Connor to tell her she realized that God was the main subject in the short story collection. “You are very kind to write to me and the measure of my appreciation must be to ask you to write to me again. I would like to know who this is who understands my stories,” O’Connor responded in a letter dated July 10, 1955.

It was the first of 274 letters O’Connor sent to Elizabeth “Betty” Hester, sparking a friendship that would continue until the Flannery O’Connor’s death from lupus in 1964.

Betty Hester, “an agnostic obsessed with God,”was shy, a flirt, and a chain-smoker with a menagerie of cats who cared for a widowed aunt named Clyde. Although she never published any of her stories, Hester shared her writing with O’Connor. Hester wrote book reviews for the diocesan newspaper, The Bulletin, as did O’Connor.

The early letters center on the two women’s faith. In the course of their correspondence, Hester converted to Catholicism, asking O’Connor to be her sponsor. Flannery tried to help Hester in her understanding of the Catholic faith in hopes of giving Betty some spiritual comfort; but shortly after her baptism, Hester decided to leave the church. That disturbed O’Connor more than Hester’s admission she was a lesbian.

After much intense correspondence and several visits, Betty insisted on telling Flannery her “history of horror” before the friendship went any further. At 13, Betty had watched her mother commit suicide. The neighbors, believing she was “playacting,” did not intervene. Betty also told O’Connor that she had served in the Air Force in Germany, but was dishonorably discharged for “sexual indiscretion” with a woman.

O’Connor responded to Hester’s revelations with this frank and nonjudgemental note: “Compared to what you have experienced in the way of radical misery, I have never had anything to bear in my life but minor irritations…If in any sense my knowing your burden can make your burden lighter, then I am doubly glad I know it. You were right to tell me, but I’m glad you didn’t tell me until I knew you well. Where you are wrong is in saying that you are the history of horror. The meaning of redemption is precisely that we do not have to be our history, and nothing is plainer to me than that you are not your history.”

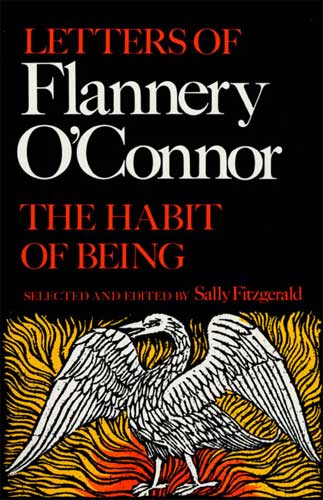

Hester and O’Connor remained friends and corresponded until O’Connor’s death. It is through the correspondence with Hester published in The Habit of Being that scholars are able to get a clear view of O’Connor’s thoughts on writing and her Catholic faith.

In 1998 Hester committed suicide with a hollow-nose bullet aimed at her skull. She died after eating a late afternoon Christmas dinner and playfully mocking her friend, William Sessions, “for taking the Church seriously.” She was 76.

June 16th, 2009 at 4:30 pm

What a great Christian was our Flannery O’Connor! And would that I could be as charitable and forgiving as she no doubt was. Her friend Betty Hester lived a tragic life; and there is much sad irony in the fact that she thought William Sessions took the Church “too seriously” just before despairing and taking her own life.

March 25th, 2010 at 12:29 am

[…] the redemption is precisely that you do not have to be your history.” Interestingly enough, she said it in the context of responding to Betty Hester, a woman who had corresponded with O’Connor for a while and […]

January 22nd, 2015 at 3:37 pm

The subtle paradox with regard to the action of redemption in cancelling the burden of our history is that one must accept grace, which, as Flannery says, is painful because it implies change, and change is hard. What does it take to accept grace if not an acknowledgment of one’s accountability for one’s history, a laying oneself bare even as one lays aside that burden? To me, that is the Sacrament of Confession, whether in a confessional before a priest or simply in the chambers of the heart. It is only then, stripped of our ridiculous (and ineffectual) attempts at concealment, that we can undergo the transformation that grace insists upon.

February 22nd, 2015 at 7:49 pm

Admitting to lesbianism in that time and place is heroic–well beyond all the sacramental nonsense you’re spewing–and clearly worthy of your “forgiveness.” I doubt O’Conner would have enjoyed being dubbed “a great Christian.” She knew her flaws as we all do. I remember now why I never wanted a Ph.D.