The Catholicism of John Rechy

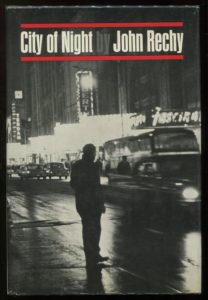

A few weeks ago I pulled out my copy of City of Night by John Rechy to reread it. It was Rechy’s first novel published in 1963. It draws on Rechy’s life, starting with growing up in El Paso, Texas, and his vocation as a hustler, starting in New York, and traveling through the very Catholic cities of Los Angles, Chicago, and New Orleans. After years of doing both, he eventually traded hustling for writing and teaching.

John Francisco Rechy was born March 10, 1931 in El Paso, Texas. He was the youngest of five children born to Guadalupe and Roberto Rechy. Both of Rechy’s parents were born in Mexico; his father had a Scottish ancestor.

He writes about a childhood religious revelation: “Soon, I stopped going to Mass. I stopped praying. The God that would allow this unhappiness was a God I would rebel against. The seeds of that rebellion—planted that ugly afternoon when I saw my dog’s body beginning to decay, that soul shut out by heaven, were beginning to germinate.” (page 17, City of Night)

In City of Night, there are no less than 32 mentions of God or Catholicism in its 380 pages. I found the “indelible mark” of Catholic sacraments and upbringing throughout his writing and statements. The hypocrisy of church offends him, and he believes many clergy are gay, but I was surprised that I did not find a bishop, priest, or seminarian in any of bars, streets, and parks he frequents in City of Night. Most gay priests I know had boyfriends or sought out casual sex at some point during their careers. It’s surprising that Rechy didn’t have a sexual encounter with one of them or chose not to write about it.

Moby Dick, Herman Melville’s “quarrel with God,” kept popping up in my head throughout City of Night. The character, “youngman,” observes the world around him; and continually questions and rebels against an indifferent, evil God. “Youngman” searches for salvation the way Ahab searches for Moby Dick. He did not find it on white sheets (page 367). He did find love, which might have meant salvation, but chose to walk away.

I have reread those pages (343-368) to understand why youngman resisted Jeremy’s offer of love. Was he homophobic? Was he afraid of a loss of control? Was the habit of resistance to any emotional involvement so strong that he could not overcome it? I never could figure it out. Whether faith, love, or sex, you must choose to surrender, and if that readiness is not there, the moment is lost.

John Rechy’s Catholicism is revealed in his writing and his interviews. He is remarkably consistent throughout the decades of his use of Catholic imagery and why and how it remains in his life and work.

“I was a late bloomer I think as part of the Catholicism. Sex was not mentioned, and didn’t exist. I learned about sex from bestselling novels like Gone With the Wind and Forever Amber. When I was about 15 the sexual urges started coming but without direction. I didn’t know what sexual direction I was going, whether it was men or women. My first (willing) male sexual contact was in the army when I was about 20 in Paris. There was a lot of sexual conflict that came into play, a lot of ambiguity. I was aware of sex before then, but it was ambiguous if I liked male or female. Finally, one led to the other and finally I identified completely as a gay man.”

“The Catholic Church profoundly influenced me, believe it or not. I’m fond of saying ‘A lapsed Catholic lapses every day.’ This influence was basically unavoidable with the Mexican background, that’s pretty profound. That accounts for the religious imagery in my books. I like to say, ‘I write in Catholic.’”

“I dislike religion very much, Christianity in particular (especially Catholicism, which is what I was born into), and find it mean and dangerous—and hypocritical about sex. Those aspects, I intertwine into many of my books.”

“Religions, Christian religious, at any rate, do offer redemption, salvation, et cetera—that is at the core of much of it: salvation. But when you finally encounter the hypocrisy and cruelty embedded in every one of those religions, you’re left with a terrible emptiness—no “salvation.” We look for substitutes: often, yes, in sex, lots of sex. Now I can see how intelligent readers might find a sense of spirituality in my writing. I would say, however, it is, more, the tenacious dregs of early religious attitudes. I use Catholic imagery constantly, and that might lead to a deduction of spirituality.”

“My mother was deeply religious, and it got her through painful times. Because of that, I often prayed with her, the rosary, et cetera. I would never have done anything to compromise that. Too, looked at objectively, the Catholic Mass is very beautiful, High Mass. On a church that only Technicolor could do justice to; the statues of saints, Mary, and Jesus all look like movie stars. The ritualized services, the changing, the spraying of incense—that provides great theater, of course. It wasn’t until I could see those rituals as such that I could tolerate them. Yes, beautiful drama at the core of which is—alas—suffering and repression and cruel judgments.”

“Mexican culture adds hateful factors to the forming of a solid homosexual identity, in main part because of the power of the Catholic church, although I would say a majority of priests and high prelates are themselves gay.”

John Rechy absolutely nailed the eroticism in Catholic art and churches.

“The imagery of Catholic art, in its churches, is erotic and—oh, yes—very often powerfully, overtly sexual—the Sistine paintings at times seem to depict orgies. And a lot of sadomasochism, a lot. Yes, and look at the image of Christ crucified in altars all over the world. What a huge impact that has to have: a beautiful man, a muscular body, almost naked, only a tantalizing covering—and a kneeling audience of priests and congregants.”

“I have always been fascinated by the sexual imagery in Catholic churches and religious art, especially depicting Christ. In representations of his crucifixion he is incredibly beautiful, his body is lithely muscular, perfect, and the loincloth covers him just above the pubic area. It is that figure that congregants are expected to kneel and “adore.” That is the figure that nuns “marry” before…And yet people are aghast to think of Jesus as a sexual figure.”

“In my book, Our Lady of Babylon, there is the most beautiful love scene between Jesus and Judas. I retell the story of the betrayal. The sex scene is told by Mary Magdalene, who’s looking down on it from a hill. Talk about artistic decision! I know that it would be very difficult to say, “And then Jesus went down on Judas, and Judas went down…” because it would be an outrage. But I wanted a full sex scene. So it’s Jesus, Judas, and Mary Magdalene. She’s in the middle, and they begin to kiss her, and then she moves slowly away, knowing that this is what it’s all about, and then they come together and kiss, and then Magdalene moves away to a hill. And then from the point of view of Magdalene, so that I don’t have to get vulgar, I describe their movements. So there it is. I’ve done that one.”

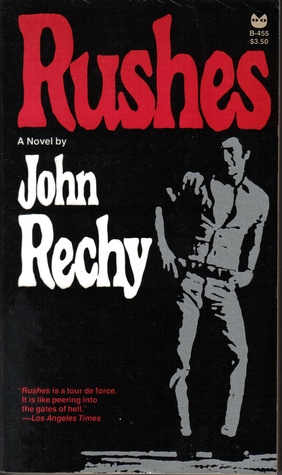

“In the novel, Rushes..I write about one night in a leather bar, a night that ends up in an S & M orgy room…The bar is described to look like an altar. The characters locate themselves in the positions of priest and acolytes during Mass. On the walls of the Rushes Bar there are sketchy erotic drawings. These find parallels in the Stations of the Cross, the last panel fading into unintelligible scrawls, to suggest the ambiguity of the possible Fifteenth Station. There is a “baptism” and an “offertory.” At the end of a metaphoric crucifixion and an actual one (gay bashing) occur simultaneously, one inside the orgy room, the other outside. The novel/Mass ends with a surrendered benediction.”

“What have I discovered? I guess I’ll go on saying there is no substitute for salvation, a phrase that appears in every one of my books; but what I may have come to believe is that what is required is to redefine the word “salvation,” by pulling it away from any religious context. Then salvation may be found in living as good a life as the terrifying world allows.”

“In my teen years, I did write some poetry (in addition to the novels I was writing). The poems were often in rhymed pentameter. I liked epic subjects. “The Crazy Fall of Man” was one, in which, at the end, Judgement Day, outraged people come to judge God, not the other way around; and the last person is Christ, so powerfully accusing God that He—God—throws himself into hell, like this: “And raising his mighty hand in an act of contrition, God said, “Forgive, forgive, forgive,” and flung Himself headlong into the bottomless pit of hell.”

John Rechy’s writing is full of incidents and feelings familiar to many gay and lesbian Catholics. Anger, especially anger at God and the church; loneliness, the ease of slipping into lies and masks, the search for sex, the feeling of empty spaces inside, and finally, the wistful longing to return to the faith of our childhood and youth. How often do we find ourselves feeling abandoned, seeking God who is absent from our life? Our search—or walking away—can go on for many years. Rechy is not indifferent about his Catholicism. Even if you care just a little, the connection is still there.

“And I was thinking that although there is no God, never was a God, and never will be One—considering the world He made, it is possible to understand Him—or that part of Him that had forbidden Knowing, because–Christ!—at that moment I longed for innocence more than anything else, and I would have thrown away all the frantic knowing for a return to a state of Grace—which is only the state of idiot-like, Not Knowing.” (page 379, City of Night)

At parties or receptions throughout the years, various men or women have asked me about my life. When I say I’m a Catholic, and believe and work for change in the Church, I’m often treated to a barrage of abuse by former Catholics. People feel entitled to rip into a self-identified Catholic in ways that they would never do to anyone else. Inevitably, three or four drinks later, this person seeks me out for another conversation. They tell me how sad they are about the Church’s rejection of them, and how much they miss the faith that they had when they were younger. I understand. How often I wished I could return to that sweet innocence. There is nothing to do but comfort them and hope they can find their way back.

Books by John Rechy

City of Night (Grove Press, 1963)

Numbers (Grove Press, 1967)

This Day’s Death (Grove Press, 1969)

The Vampires (Grove Press, 1971)

The Fourth Angel (Viking, 1972)

The Sexual Outlaw (Grove Press, 1977)

Rushes (Grove Press, 1979)

Bodies and Souls (Carroll & Graf) 1983

Marilyn’s Daughter (Carroll & Graf) 1988

The Miraculous Day of Amalia Gomez (Arcade, 1991)

Our Lady of Babylon (Arcade, 1996)

The Coming of the Night (Grove Press, 1999)

The Life and Adventures of Lyle Clemens (Grove Press, 2003)

Beneath the Skin (Carroll & Graf, 2004)

About My Life and the Kept Woman (Grove Press, 2008, memoir)

After the Blue Hour (Grove Press, 2017)

Pablo! (Arte Publico Press, 2018)

Books About John Rechy

Outlaw: The Lives and Careers of John Rechy by Charles Casillo (Advocate Books, 2002)

Understanding John Rechy by Maria DeGuzman (University of South Carolina Press, 2019)